Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

7073.3 Step 3: Determine Risk of Material Misstatement and Testing Approach

Sep-2022

In This Section

- Inherent Risk Factors and Our Risk Assessment Framework

- Estimation Uncertainty

- Complexity and Subjectivity

- Other Inherent Risk Factors

- Interrelationships Between Inherent Risk Factors

- Assess Level of Inherent Risk

- Assessing Inherent Risk—Scalability

Determine Audit Approach for Testing Estimate

- Determine Audit Approach

- Obtain Evidence from Events Occurring up to Date of Auditor’s Report

- Test How Management Made the Estimate

- Develop Auditor’s Point Estimate or Range

- Test Operating Effectiveness of Controls

Assess Inherent Risk

CAS Requirement

In identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatement relating to an accounting estimate and related disclosures at the assertion level, including separately assessing inherent risk and control risk at the assertion level, as required by CAS 315, the auditor shall take the following into account in identifying the risks of material misstatement and in assessing inherent risk (CAS 540.16):

(a) The degree to which the accounting estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty; and

(b) The degree to which the following are affected by complexity, subjectivity, or other inherent risk factors:

(i) The selection and application of the method, assumptions and data in making the accounting estimate; or

(ii) The selection of management’s point estimate and related disclosures for inclusion in the financial statements.

Inherent Risk Factors and Our Risk Assessment Framework

CAS Guidance

Identifying and assessing risks of material misstatement at the assertion level relating to accounting estimates is important for all accounting estimates, including not only those that are recognized in the financial statements, but also those that are included in the notes to the financial statements (CAS 540.A64).

Paragraph A44 of CAS 200 states that the CASs typically refer to the “risks of material misstatement” rather than to inherent risk and control risk separately. CAS 315 requires a separate assessment of inherent risk and control risk to provide a basis for designing and performing further audit procedures to respond to the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, including significant risks, in accordance with CAS 330 (CAS 540.A65).

In identifying the risks of material misstatement and in assessing inherent risk for accounting estimates in accordance with CAS 315, the auditor is required to take into account the inherent risk factors that affect susceptibility to misstatement of assertions, and how they do so. The auditor’s consideration of the inherent risk factors may also provide information to be used in:

-

Assessing the likelihood and magnitude of misstatement (i.e., where inherent risk is assessed on the spectrum of inherent risk); and

-

Determining the reasons for the assessment given to the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, and that the auditor’s further audit procedures in accordance with paragraph 18 are responsive to those reasons.

The interrelationships between the inherent risk factors are further explained in Appendix 1 (CAS 540.A66).

OAG Guidance

CAS 540.16 requires that in assessing inherent risk, we take into account the degree to which an estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty, and the degree to which it is affected by complexity, subjectivity or other inherent risk factors.

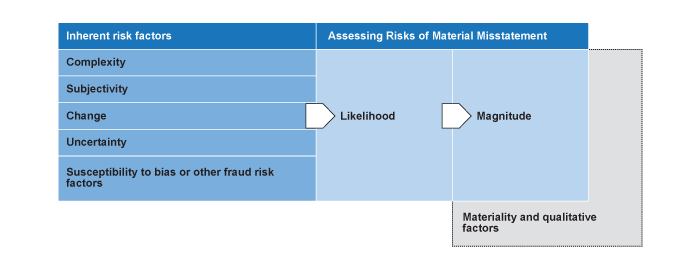

The degree to which estimates are affected by these factors, individually and in combination, is important in identifying risks of material misstatement and assessing the level of inherent risk. Our risk assessment framework (as set out in section Our risk assessment framework in OAG Audit 5043.3) introduces a need to consider the likelihood and magnitude of a potential misstatement. Having assessed the impact of estimation uncertainty and inherent risk factors, we will be in a position to assess the likelihood of a misstatement. In order to assess the potential magnitude of a misstatement, we need to consider materiality and other relevant qualitative factors, as illustrated below and consistent with the guidance in OAG Audit 5043.3 on our overall risk assessment framework.

Note that in addition to the inherent risk factors of estimation uncertainty, complexity, and subjectivity, which are specifically included in CAS 540, we also need to evaluate other inherent risk factors included in CAS 315. These include inherent risk factors of change and susceptibility to bias or other fraud risk factors. For general guidance on evaluating inherent risk factors in accordance with CAS 315, refer to OAG Audit 5043.3.

The impact of inherent factors on our assessment of inherent risk is discussed in detail in the section Assess Level of Inherent Risk below.

Estimation Uncertainty

CAS Guidance

In taking into account the degree to which the accounting estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty, the auditor may consider (CAS 540.A72):

-

Whether the applicable financial reporting framework requires:

- The use of a method to make the accounting estimate that inherently has a high level of estimation uncertainty. For example, the financial reporting framework may require the use of unobservable inputs.

- The use of assumptions that inherently have a high level of estimation uncertainty, such as assumptions with a long forecast period, assumptions that are based on data that is unobservable and are therefore difficult for management to develop, or the use of various assumptions that are interrelated.

- Disclosures about estimation uncertainty.

-

The business environment. An entity may be active in a market that experiences turmoil or possible disruption (for example, from major currency movements or inactive markets) and the accounting estimate may therefore be dependent on data that is not readily observable.

-

Whether it is possible (or practicable, insofar as permitted by the applicable financial reporting framework) for management:

- To make a precise and reliable prediction about the future realization of a past transaction (for example, the amount that will be paid under a contingent contractual term), or about the incidence and impact of future events or conditions (for example, the amount of a future credit loss or the amount at which an insurance claim will be settled and the timing of its settlement); or

- To obtain precise and complete information about a present condition (for example, information about valuation attributes that would reflect the perspective of market participants at the date of the financial statements, to develop a fair value estimate).

The size of the amount recognized or disclosed in the financial statements for an accounting estimate is not, in itself, an indicator of its susceptibility to misstatement because, for example, the accounting estimate may be understated (CAS 540.A73).

In some circumstances, the estimation uncertainty may be so high that a reasonable accounting estimate cannot be made. The applicable financial reporting framework may preclude recognition of an item in the financial statements, or its measurement at fair value. In such cases, there may be risks of material misstatement that relate not only to whether an accounting estimate should be recognized, or whether it should be measured at fair value, but also to the reasonableness of the disclosures. With respect to such accounting estimates, the applicable financial reporting framework may require disclosure of the accounting estimates and the estimation uncertainty associated with them (see paragraphs A112–A113, A143–A144) (CAS 540.A74).

In some cases, the estimation uncertainty relating to an accounting estimate may cast significant doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. CAS 570 establishes requirements and provides guidance in such circumstances (CAS 540.A75).

OAG Guidance

Examples of estimates where estimation uncertainty may be higher

-

Litigation with potentially material exposure where the amount of resulting obligation cannot be accurately predicted.

-

A significant impairment provision with long forecast period used for calculation of value in use and highly sensitive to changes in significant assumptions (e.g., projected revenue growth).

-

Estimates where historically there have been significant differences between the management estimate and actual outcome (as identified by retrospective reviews).

Complexity and Subjectivity

CAS Guidance

In taking into account the degree to which the selection and application of the method used in making the accounting estimate are affected by complexity, the auditor may consider (CAS 540.A76):

-

The need for specialized skills or knowledge by management which may indicate that the method used to make an accounting estimate is inherently complex and therefore the accounting estimate may have a greater susceptibility to material misstatement. There may be a greater susceptibility to material misstatement when management has developed a model internally and has relatively little experience in doing so, or uses a model that applies a method that is not established or commonly used in a particular industry or environment.

-

The nature of the measurement basis required by the applicable financial reporting framework, which may result in the need for a complex method that requires multiple sources of historical and forward-looking data or assumptions, with multiple interrelationships between them. For example, an expected credit loss provision may require judgments about future credit repayments and other cash flows, based on consideration of historical experience data and the application of forward looking assumptions. Similarly, the valuation of an insurance contract liability may require judgments about future insurance contract payments to be projected based on historical experience and current and assumed future trends.

In taking into account the degree to which the selection and application of the data used in making the accounting estimate are affected by complexity, the auditor may consider (CAS 540.A77):

-

The complexity of the process to derive the data, taking into account the relevance and reliability of the data source. Data from certain sources may be more reliable than from others. Also, for confidentiality or proprietary reasons, some external information sources will not (or not fully) disclose information that may be relevant in considering the reliability of the data they provide, such as the sources of the underlying data they used or how it was accumulated and processed

-

The inherent complexity in maintaining the integrity of the data. When there is a high volume of data and multiple sources of data, there may be inherent complexity in maintaining the integrity of data that is used to make an accounting estimate.

-

The need to interpret complex contractual terms. For example, the determination of cash inflows or outflows arising from a commercial supplier or customer rebates may depend on very complex contractual terms that require specific experience or competence to understand or interpret.

In taking into account the degree to which the selection and application of method, assumptions or data are affected by subjectivity, the auditor may consider (CAS 540.A78):

-

The degree to which the applicable financial reporting framework does not specify the valuation approaches, concepts, techniques and factors to use in the estimation method.

-

The uncertainty regarding the amount or timing, including the length of the forecast period. The amount and timing are a source of inherent estimation uncertainty, and give rise to the need for management judgment in selecting a point estimate, which in turn creates an opportunity for management bias. For example, an accounting estimate that incorporates forward looking assumptions may have a high degree of subjectivity which may be susceptible to management bias.

OAG Guidance

Complexity

Complexity may increase the inherent risk associated with an accounting estimate because management’s reliance on a complex process increases the likelihood that data, assumptions or the model itself will be misidentified, misunderstood or misapplied. Misstatements in this regard may be more likely in the case of estimates whose outcome is resolved over a longer period of time and where little evidence is available when management makes the estimate, for example post-employment benefit liabilities or liabilities estimated based on actuarial projections and calculations.

Where evidence over the estimate is available after the balance sheet date, even though the estimation technique itself may be complex, the inherent risk of misstatement may not be higher than a normal risk. For example, the entity’s information system may use complex calculations to determine the inventory obsolescence provision, but evidence available to management after the year end (such as the sale of inventory supporting its estimated net realizable value) may enable management to adjust the estimate to reflect this information and reduce the risk of misstatement.

Where we identify that management’s estimate is subject to complexity, we consider whether it is necessary for us to engage a specialist in accounting or auditing or an auditor’s expert to assist with identifying and/or responding to the assessed risks of material misstatement. For example, entities may use complex modelling to calculate the valuation of post-employment benefit liabilities, and it is unlikely that we will be able to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence over the estimated liability without support from an actuarial expert. Examples of the different types of specialists in accounting or auditing or auditor’s experts that we may engage for the purposes of auditing a complex estimate are included in the section Examples of auditor’s internal experts and specialists in accounting or auditing in OAG Audit 3092.

We consider whether management’s use of its own expert indicates complexity in the estimation process, and may therefore be a factor to consider when deciding, at the planning stage, whether the engagement team requires specialized skills or knowledge. Where we conclude that specialized skills or knowledge are necessary, and management has not involved its own expert this may itself inform our assessment of inherent risk as the likelihood of a misstatement may be increased. Further guidance on the involvement of specialists and experts in the audit can be found in the section Involvement of Auditor’s Experts and Specialists in OAG Audit 7073.2.

Subjectivity

For estimated amounts where there is estimation uncertainty, management will need to exercise judgment in the selection of methods, assumptions and data to calculate a point estimate or range, and in the determination and recognition of the estimate and the related disclosures to be included in the financial statements. This gives rise to subjectivity because the exercise of judgment is likely to be based on management’s experiences, preferences and opinions. This may, in turn, give rise to opportunities for management to introduce bias.

For example, in recognizing and measuring a provision for a legal claim, the best estimate of the expenditure required to settle the obligation is to be determined by management for recognition at the end of the reporting period where the appropriate criteria for recognition specified by the applicable financial reporting framework are met. Management’s determination of the expected outcome and of the best estimate of the expected settlement require the use of judgment by management of the entity, supplemented by experience of any similar claims and, in some cases, reports from management’s experts. The evidence considered includes any additional evidence provided by events after the reporting period.

If the applicable financial reporting framework prescribes specific approaches or techniques to be used in measuring the estimate (including a particular method or a particular source or type of data and/or assumption), this may reduce the degree of subjectivity. It is therefore important for us to understand the requirements of the financial reporting framework as they relate to accounting estimates when assessing the risk of material misstatement (see related guidance in the section Requirements of the Applicable Financial Reporting Framework in OAG Audit 7072).

Other Inherent Risk Factors

CAS Guidance

When assessing the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, in addition to estimation uncertainty, complexity, and subjectivity, the auditor also takes into account the degree to which inherent risk factors included in CAS 315 (other than estimation uncertainty, complexity, and subjectivity), affect susceptibility of assertions to misstatement about the accounting estimate. Such additional inherent risk factors include (CAS 540.A9):

-

Change in the nature or circumstances of the relevant financial statement items, or requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework which may give rise to the need for changes in the method, assumptions or data used to make the accounting estimate.

-

Susceptibility to misstatement due to management bias, or other fraud risk factors insofar as they affect inherent risk, in making the accounting estimate.

-

Uncertainty, other than estimation uncertainty.

The degree of subjectivity associated with an accounting estimate influences the susceptibility of the accounting estimate to misstatement due to management bias or other fraud risk factors insofar as they affect inherent risk. For example, when an accounting estimate is subject to a high degree of subjectivity, the accounting estimate is likely to be more susceptible to misstatement due to management bias or fraud and this may result in a wide range of possible measurement outcomes. Management may select a point estimate from that range that is inappropriate in the circumstances, or that is inappropriately influenced by unintentional or intentional management bias, and that is therefore misstated. For continuing audits, indicators of possible management bias identified during the audit of preceding periods may influence the planning and risk assessment procedures in the current period. (CAS 540.A79)

OAG Guidance

Changes in circumstances that give rise to the need for changes in accounting estimates may be specified in the applicable financial reporting framework. However, examples might include:

-

Restructuring or reorganization of operations that leads to a need to redefine cash generating units for the purposes of impairment testing;

-

Change in the process for determining standard inventory costs leading to a change in how capitalizable variances are determined at the period end; or

-

Capital enhancements to property, plant and equipment that result in an extended useful economic life.

Certain estimates may be more susceptible to bias than others, either because of their inherent subjectivity or because of other factors identified in our risk assessment. We consider whether this bias may be conscious or unconscious. Conscious bias might indicate an intention to mislead, which is fraudulent in nature (CAS 540.32) and would need to be taken into account in our fraud risk assessment under CAS 240. Examples of where we might identify indicators of management bias are set out in the section Management Bias in OAG Audit 7071. Where we identify a risk of material misstatement due to fraud, this risk is required to be assessed as significant in accordance with CAS 240.

Interrelationships Between Inherent Risk Factors

CAS Guidance

Inherent Risk Factors (CAS 540 –Appendix 1)

Introduction

1. In identifying, assessing and responding to the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level for an accounting estimate and related disclosures, this CAS requires the auditor to take into account the degree to which the accounting estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty, and the degree to which the selection and application of the methods, assumptions and data used in making the accounting estimate, and the selection of management’s point estimate and related disclosures for inclusion in the financial statements, are affected by complexity, subjectivity or other inherent risk factors.

2. Inherent risk related to an accounting estimate is the susceptibility of an assertion about the accounting estimate to material misstatement, before consideration of controls. Inherent risk results from inherent risk factors, which give rise to challenges in appropriately making the accounting estimate. This Appendix provides further explanation about the nature of the inherent risk factors of estimation uncertainty, subjectivity and complexity, and their inter-relationships, in the context of making accounting estimates and selecting management’s point estimate and related disclosures for inclusion in the financial statements.

Measurement Basis

3. The measurement basis and the nature, condition and circumstances of the financial statement item give rise to relevant valuation attributes. When the cost or price of the item cannot be directly observed, an accounting estimate is required to be made by applying an appropriate method and using appropriate data and assumptions. The method may be specified by the applicable financial reporting framework, or is selected by management, to reflect the available knowledge about how the relevant valuation attributes would be expected to influence the cost or price of the item on the measurement basis.

Estimation Uncertainty

4. Susceptibility to a lack of precision in measurement is often referred to in accounting frameworks as measurement uncertainty. Estimation uncertainty is defined in this CAS as susceptibility to an inherent lack of precision in measurement. It arises when the required monetary amount for a financial statement item that is recognized or disclosed in the financial statements cannot be measured with precision through direct observation of the cost or price. When direct observation is not possible, the next most precise alternative measurement strategy is to apply a method that reflects the available knowledge about cost or price for the item on the relevant measurement basis, using observable data about relevant valuation attributes.

5. However, constraints on the availability of such knowledge or data may limit the verifiability of such inputs to the measurement process and therefore limit the precision of measurement outcomes. Furthermore, most accounting frameworks acknowledge that there are practical constraints on the information that should be taken into account, such as when the cost of obtaining it would exceed the benefits. The lack of precision in measurement arising from these constraints is inherent because it cannot be eliminated from the measurement process. Accordingly, such constraints are sources of estimation uncertainty. Other sources of measurement uncertainty that may occur in the measurement process are, at least in principle, capable of elimination if the method is applied appropriately and therefore are sources of potential misstatement rather than estimation uncertainty.

6. When estimation uncertainty relates to uncertain future inflows or outflows of economic benefits that will ultimately result from the underlying asset or liability, the outcome of these flows will only be observable after the date of the financial statements. Depending on the nature of the applicable measurement basis and on the nature, condition and circumstances of the financial statement item, this outcome may be directly observable before the financial statements are finalized or may only be directly observable at a later date. For some accounting estimates, there may be no directly observable outcome at all.

7. Some uncertain outcomes may be relatively easy to predict with a high level of precision for an individual item. For example, the useful life of a production machine may be easily predicted if sufficient technical information is available about its average useful life. When it is not possible to predict a future outcome, such as an individual’s life expectancy based on actuarial assumptions, with reasonable precision, it may still be possible to predict that outcome for a group of individuals with greater precision. Measurement bases may, in some cases, indicate a portfolio level as the relevant unit of account for measurement purposes, which may reduce inherent estimation uncertainty.

Complexity

8. Complexity (i.e., the complexity inherent in the process of making an accounting estimate, before consideration of controls) gives rise to inherent risk. Inherent complexity may arise when:

-

There are many valuation attributes with many or non‑linear relationships between them.

-

Determining appropriate values for one or more valuation attributes requires multiple data sets.

-

More assumptions are required in making the accounting estimate, or when there are correlations between the required assumptions.

-

The data used is inherently difficult to identify, capture, access or understand.

9. Complexity may be related to the complexity of the method and of the computational process or model used to apply it. For example, complexity in the model may reflect the need to apply probability-based valuation concepts or techniques, option pricing formulae or simulation techniques to predict uncertain future outcomes or hypothetical behaviors. Similarly, the computational process may require data from multiple sources, or multiple data sets to support the making of an assumption or the application of sophisticated mathematical or statistical concepts.

10. The greater the complexity, the more likely it is that management will need to apply specialized skills or knowledge in making an accounting estimate or engage a management’s expert, for example in relation to:

-

Valuation concepts and techniques that could be used in the context of the measurement basis and objectives or other requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework and how to apply those concepts or techniques;

-

The underlying valuation attributes that may be relevant given the nature of the measurement basis and the nature, condition and circumstances of the financial statement items for which accounting estimates are being made; or

-

Identifying appropriate sources of data from internal sources (including from sources outside the general or subsidiary ledgers) or from external information sources, determining how to address potential difficulties in obtaining data from such sources or in maintaining its integrity in applying the method, or understanding the relevance and reliability of that data.

11. Complexity relating to data may arise, for example, in the following circumstances:

a) When data is difficult to obtain or when it relates to transactions that are not generally accessible. Even when such data is accessible, for example through an external information source, it may be difficult to consider the relevance and reliability of the data, unless the external information source discloses adequate information about the underlying data sources it has used and about any data processing that has been performed.

b) When data reflecting an external information source’s views about future conditions or events, which may be relevant in developing support for an assumption, is difficult to understand without transparency about the rationale and information taken into account in developing those views.

c) When certain types of data are inherently difficult to understand because they require an understanding of technically complex business or legal concepts, such as may be required to properly understand data that comprises the terms of legal agreements about transactions involving complex financial instruments or insurance products.

Subjectivity

12. Subjectivity (i.e., the subjectivity inherent in the process of making an accounting estimate, before consideration of controls) reflects inherent limitations in the knowledge or data reasonably available about valuation attributes. When such limitations exist, the applicable financial reporting framework may reduce the degree of subjectivity by providing a required basis for making certain judgments. Such requirements may, for example, set explicit or implied objectives relating to measurement, disclosure, the unit of account, or the application of a cost constraint. The applicable financial reporting framework may also highlight the importance of such judgments through requirements for disclosures about those judgments.

13. Management judgment is generally needed in determining some or all of the following matters, which often involve subjectivity:

-

To the extent not specified under the requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework, the appropriate valuation approaches, concepts, techniques and factors to use in the estimation method, having regard to available knowledge;

-

To the extent valuation attributes are observable when there are various potential sources of data, the appropriate sources of data to use;

-

To the extent valuation attributes are not observable, the appropriate assumptions or range of assumptions to make, having regard to the best available data, including, for example, market views;

-

The range of reasonably possible outcomes from which to select management’s point estimate, and the relative likelihood that certain points within that range would be consistent with the objectives of the measurement basis required by the applicable financial reporting framework; and

-

The selection of management’s point estimate, and the related disclosures to be made, in the financial statements.

14. Making assumptions about future events or conditions involves the use of judgment, the difficulty of which varies with the degree to which those events or conditions are uncertain. The precision with which it is possible to predict uncertain future events or conditions depends on the degree to which those events or conditions are determinable based on knowledge, including knowledge of past conditions, events and related outcomes. The lack of precision also contributes to estimation uncertainty, as described above.

15. With respect to future outcomes, assumptions will only need to be made for those features of the outcome that are uncertain. For example, in considering the measurement of a possible impairment of a receivable for a sale of goods at the balance sheet date, the amount of the receivable may be unequivocally established and directly observable in the related transaction documents. What may be uncertain is the amount, if any, for loss due to impairment. In this case, assumptions may only be required about the likelihood of loss and about the amount and timing of any such loss.

16. However, in other cases, the amounts of cash flows embodied in the rights relating to an asset may be uncertain. In those cases, assumptions may have to be made about both the amounts of the underlying rights to cash flows and about potential losses due to impairment.

17. It may be necessary for management to consider information about past conditions and events, together with current trends and expectations about future developments. Past conditions and events provide historical information that may highlight repeating historical patterns that can be extrapolated in evaluating future outcomes. Such historical information may also indicate changing patterns of such behavior over time (cycles or trends). These may suggest that the underlying historical patterns of behavior have been changing in somewhat predictable ways that may also be extrapolated in evaluating future outcomes. Other types of information may also be available that indicate possible changes in historical patterns of such behavior or in related cycles or trends. Difficult judgments may be needed about the predictive value of such information.

18. The extent and nature (including the degree of subjectivity involved) of the judgments taken in making the accounting estimates may create opportunity for management bias in making decisions about the course of action that, according to management, is appropriate in making the accounting estimate. When there is also a high level of complexity or a high level of estimation uncertainty, or both, the risk of, and opportunity for, management bias or fraud may also be increased.

Relationship of Estimation Uncertainty to Subjectivity and Complexity

19. Estimation uncertainty gives rise to inherent variation in the possible methods, data sources and assumptions that could be used to make an accounting estimate. This gives rise to subjectivity, and hence, the need for the use of judgment in making the accounting estimate. Such judgments are required in selecting the appropriate methods and data sources, in making the assumptions, and in selecting management’s point estimate and related disclosures for inclusion in the financial statements. These judgments are made in the context of the recognition, measurement, presentation and disclosure requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework. However, because there are constraints on the availability and accessibility of knowledge or information to support these judgments, they are subjective in nature.

20. Subjectivity in such judgments creates the opportunity for unintentional or intentional management bias in making them. Many accounting frameworks require that information prepared for inclusion in the financial statements should be neutral (i.e., that it should not be biased). Given that bias can, at least in principle, be eliminated from the estimation process, sources of potential bias in the judgments made to address subjectivity are sources of potential misstatement rather than sources of estimation uncertainty.

21. The inherent variation in the possible methods, data sources and assumptions that could be used to make an accounting estimate (see paragraph 19) also gives rise to variation in the possible measurement outcomes. The size of the range of reasonably possible measurement outcomes results from the degree of estimation uncertainty and is often referred to as the sensitivity of the accounting estimate. In addition to determining measurement outcomes, an estimation process also involves analyzing the effect of inherent variations in the possible methods, data sources and assumptions on the range of reasonably possible measurement outcomes (referred to as sensitivity analysis).

22. Developing a financial statement presentation for an accounting estimate, which, when required by the applicable financial reporting framework, achieves faithful representation (i.e., complete, neutral and free from error) includes making appropriate judgments in selecting a management point estimate that is appropriately chosen from within the range of reasonably possible measurement outcomes and related disclosures that appropriately describe the estimation uncertainty. These judgments may themselves involve subjectivity, depending on the nature of the requirements in the applicable financial reporting framework that address these matters. For example, the applicable financial reporting framework may require a specific basis (such as a probability weighted average or a best estimate) for the selection of the management point estimate. Similarly, it may require specific disclosures or disclosures that meet specified disclosure objectives or additional disclosures that are required to achieve fair presentation in the circumstances.

23. Although an accounting estimate that is subject to a higher degree of estimation uncertainty may be less precisely measurable than one subject to a lower degree of estimation uncertainty, the accounting estimate may still have sufficient relevance for users of the financial statements to be recognized in the financial statements if, when required by the applicable financial reporting framework, a faithful representation of the item can be achieved. In some cases, estimation uncertainty may be so great that the recognition criteria in the applicable financial reporting framework are not met and the accounting estimate cannot be recognized in the financial statements. Even in these circumstances, there may still be relevant disclosure requirements, for example to disclose the point estimate or range of reasonably possible measurement outcomes and information describing the estimation uncertainty and constraints in recognizing the item. The requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework that apply in these circumstances may be specified to a greater or lesser degree. Accordingly, in these circumstances, there may be additional judgments that involve subjectivity to be made.

OAG Guidance

Where the estimate is subject to a higher degree of estimation uncertainty, or where it is more greatly affected by a combination of inherent risk factors, the assessed level of inherent risk is likely to be higher. Consider how inherent risk factors interact with each other, and with estimation uncertainty, when assessing inherent risks.

Appendix 1 to CAS 540 provides guidance on the inter-relationships between estimation uncertainty and inherent risk factors. The relationships between these factors will likely vary from engagement to engagement (and from estimate to estimate), and may in practice be difficult to define. However, the following are examples of relationships that are likely to exist between risk factors:

-

Estimation uncertainty gives rise to subjectivity because of the inherent limitations in availability of knowledge or data associated with an estimate. Consequently, as the degree to which an estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty increases, potentially so does the level of judgement and therefore subjectivity around the selection of methods, assumptions and data and of an appropriate point estimate and disclosures;

-

Equally, estimation uncertainty may also increase where assumptions are subject to higher subjectivity, because this results in a wider range of possible outcomes and therefore inherently less ability to precisely estimate the outcome.

-

The degree of subjectivity associated with an estimate influences the susceptibility of the estimate to management bias or fraud, such that where subjectivity is higher there is a greater opportunity for management to exercise bias. Where bias is associated with an intention to mislead, it is fraudulent in nature.

-

Where estimation uncertainty or complexity, or both, are higher, the risk of, and opportunity for, management bias or fraud may be increased. Conversely, since management bias can, at least in principle, be eliminated from the estimation process, it is a source of potential misstatement not estimation uncertainty. As such, an estimate could be affected by a high degree of bias, while still being subject to only a low degree of estimation uncertainty.

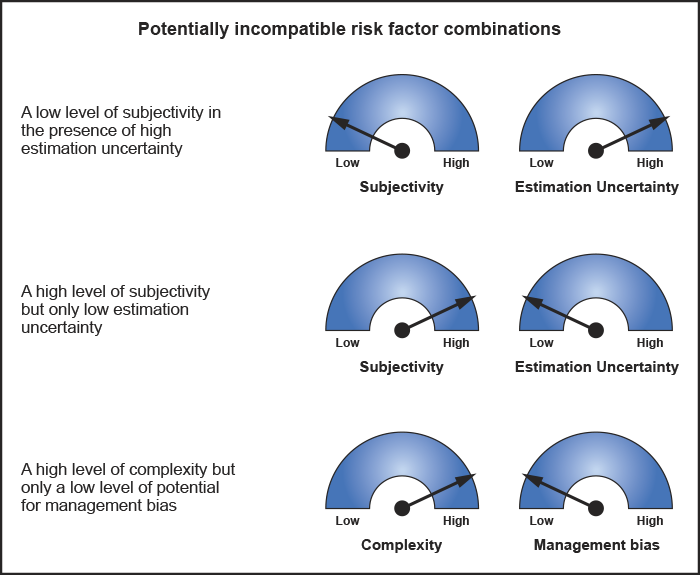

We exercise professional judgement when identifying these, and other, inter-relationships that might exist between risk factors, and consider their impact, on an individual and combined basis, on the assessment of inherent risk. It may be helpful to consider whether any of their assessments of the risk factors are incompatible based on engagement-specific circumstances, for example the following combinations are expected to be less common and would need careful consideration and, if deemed appropriate, would warrant documentation of the factors leading to the assessment:

Also consider other examples of potentially inherent risk factor selections in OAG Audit 5043.3.

Assess Level of Inherent Risk

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall determine whether any of the risks of material misstatement identified and assessed in accordance with paragraph 16 are, in the auditor’s judgment, a significant risk. If the auditor has determined that a significant risk exists, the auditor shall identify controls that address that risk, and evaluate whether such controls have been designed effectively, and determine whether they have been implemented (CAS 540.17).

For a significant risk relating to an accounting estimate, the auditor’s further audit procedures shall include tests of controls in the current period if the auditor plans to rely on those controls. When the approach to a significant risk consists only of substantive procedures, those procedures shall include tests of details (CAS 540.20).

CAS Guidance

Identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatement

The reasons for the auditor’s assessment of inherent risk at the assertion level may result from one or more of the inherent risk factors of estimation uncertainty, complexity, subjectivity or other inherent risk factors. For example (CAS 540.A67):

(a) Accounting estimates of expected credit losses are likely to be complex because the expected credit losses cannot be directly observed and may require the use of a complex model. The model may use a complex set of historical data and assumptions about future developments in a variety of entity specific scenarios that may be difficult to predict. Accounting estimates for expected credit losses are also likely to be subject to high estimation uncertainty and significant subjectivity in making judgments about future events or conditions. Similar considerations apply to insurance contract liabilities.

(b) An accounting estimate for an obsolescence provision for an entity with a wide range of different inventory types may require complex systems and processes, but may involve little subjectivity and the degree of estimation uncertainty may be low, depending on the nature of the inventory.

(c) Other accounting estimates may not be complex to make but may have high estimation uncertainty and require significant judgment, for example, an accounting estimate that requires a single critical judgment about a liability, the amount of which is contingent on the outcome of the litigation.

The relevance and significance of inherent risk factors may vary from one estimate to another. Accordingly, the inherent risk factors may, either individually or in combination, affect simple accounting estimates to a lesser degree and the auditor may identify fewer risks or assess inherent risk close to the lower end of the spectrum of inherent risk (CAS 540.A68).

Conversely, the inherent risk factors may, either individually or in combination, affect complex accounting estimates to a greater degree, and may lead the auditor to assess inherent risk at the higher end of the spectrum of inherent risk. For these accounting estimates, the auditor’s consideration of the effects of the inherent risk factors is likely to directly affect the number and nature of identified risks of material misstatement, the assessment of such risks, and ultimately the persuasiveness of the audit evidence needed in responding to the assessed risks. Also, for these accounting estimates the auditor’s application of professional skepticism may be particularly important. (CAS 540.A69)

Events occurring after the date of the financial statements may provide additional information relevant to the auditor’s assessment of the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level. For example, the outcome of an accounting estimate may become known during the audit. In such cases, the auditor may assess or revise the assessment of the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, regardless of how the inherent risk factors affect susceptibility of assertions to misstatement relating to the accounting estimate. Events occurring after the date of the financial statements also may influence the auditor’s selection of the approach to testing the accounting estimate in accordance with paragraph 18. For example, for a simple bonus accrual that is based on a straightforward percentage of compensation for selected employees, the auditor may conclude that there is relatively little complexity or subjectivity in making the accounting estimate, and therefore may assess inherent risk at the assertion level close to the lower end of the spectrum of inherent risk. The payment of the bonuses subsequent to period end may provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence regarding the assessed risks of material misstatement at the assertion level (CAS 540.A70).

Significant risks

The auditor’s assessment of inherent risk, which takes into account the degree to which an accounting estimate is subject to, or affected by estimation uncertainty, complexity, subjectivity or other inherent risk factors, assists the auditor in determining whether any of the risks of material misstatement identified and assessed are a significant risk. (CAS 540.A80)

When the auditor’s further audit procedures in response to a significant risk consist only of substantive procedures, CAS 330 requires that those procedures include tests of details. Such tests of details may be designed and performed under each of the approaches described in paragraph 18 of this CAS based on the auditor’s professional judgment in the circumstances. Examples of tests of details for significant risks related to accounting estimates include (CAS 540.A90):

- Examination, for example, examining contracts to corroborate terms or assumptions.

- Recalculation, for example, verifying the mathematical accuracy of a model.

- Agreeing assumptions used to supporting documentation, such as third-party published information.

OAG Guidance

The level of inherent risk depends on the extent to which the estimate is affected by estimation uncertainty and the inherent risk factors. Where estimation uncertainty and inherent risk factors are assessed as having a higher impact on an estimate, the likelihood of a misstatement is greater and this indicates a higher level of inherent risk. The scale over which inherent risk varies based on these factors is referred to in CAS 540.3 as the spectrum of inherent risk.

As illustrated in the section Inherent Risk Factors and Our Risk Assessment Framework above, having assessed the degree to which an estimate is subject to estimation uncertainty and affected by complexity, subjectivity and other inherent risk factors, we will be in a position to conclude on the nature of the identified risks of misstatement, and the likelihood that a misstatement will occur.

Furthermore, the assessment of inherent risk factors will likely inform our conclusion regarding the nature and level of an inherent risk. For example, if we have identified opportunities in the estimation process for management to significantly impact the estimate by introducing bias, we may conclude that there is a risk of material misstatement due to fraud. Such a risk is to be assessed as a significant risk in accordance with CAS 240.28.

We assess the level of inherent risk in accordance with the risk assessment framework in the section Our Risk Assessment Framework in OAG Audit 5043.1, considering the magnitude of potential misstatements, in combination with our assessment of nature and likelihood.

In assessing the magnitude of a potential misstatement, we consider materiality within the context of the estimate, including any relevant qualitative factors. However, the size of the related account balance relative to materiality will not always be relevant in determining the magnitude of a potential misstatement. For example, a recognized provision for litigation may itself be immaterial, but could be materially understated.

The assessment of likelihood and magnitude, and where the estimate sits on the spectrum of inherent risk, is a matter of professional judgment. However, the results of sensitivity analysis (for example, as performed by management to identify significant assumptions) may be useful in determining the likelihood of material misstatements, when considered in combination with other relevant factors. For example, if sensitivity analysis indicates that measurement of an estimate is materially affected by reasonable variations in certain assumptions, this may indicate that there is a higher likelihood of material misstatement.

This assessment may also be informed by the results of our review of the outcome of previous accounting estimates (as addressed in the section Control Activities Relevant to the Audit Over Management’s Process for Making Accounting Estimates in OAG Audit 7073.1), including whether that review identifies information regarding the susceptibility of accounting estimates to, or indicators of, management bias.

Documentation

We document our assessment of the level of inherent risk for each accounting estimate by adding and associating each accounting estimate with one or more specific risks of material misstatement and documenting our inherent risk conclusions, including the assessment of inherent risk factors, for each of these risks.

See OAG Audit 4027 for further guidance on significant risks. Note that significant risks require specific audit consideration and evaluation of related internal controls.

Assessing Inherent Risk—Scalability

OAG Guidance

The table below illustrates how our understanding of two accounting estimates impacting the same FSLI can lead to very different levels of effort when we assess inherent risks. The example accounting estimates used align with those included in the section Obtaining an Understanding of Accounting Estimates –Scalability in OAG Audit 7073.1 which provides an illustration of how the nature and extent of the procedures we perform to obtain an understanding of these accounting estimates will also vary depending on their nature.

The assessments of inherent risk illustrated below will differ based on engagement-specific facts and circumstances and the illustration is not intended to represent the audit documentation that would need to be prepared.

Note that the illustration below focuses only on selected elements of the understanding we are required to obtain in accordance with CAS 540. The illustrations are included for reference purposes only and the nature, timing and extent of procedures performed for similar accounting estimates will differ based on engagement-specific facts and circumstances. Furthermore, they are not intended to represent examples of audit documentation but instead a directional indication of the extent of understanding that is to be obtained for different accounting estimates.

| PP&E –Depreciation expense | Net realizable value of inventory | Provision for litigation | PP&E –Recoverable amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of accounting estimate | |||

| Depreciation expense for plant and machinery and office equipment calculated on a straight- line basis using estimated useful economic lives and residual values. | Estimated net realizable value of inventory, measured at the product level. | Estimated damages and costs payable in association with a legal claim. | Estimate of recoverable amount of specialized assets to assess whether an impairment loss exists. |

| Degree of uncertainty (including estimation uncertainty) | |||

| Low | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Impact of complexity on making the accounting estimate | |||

| Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Impact of subjectivity on making the accounting estimate | |||

| Low | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Impact of change | |||

| Low | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Impact of susceptibility to bias or other fraud risk factors | |||

| Low | Low | Moderate | High |

| Assessed level of inherent risk (also reflecting magnitude of potential misstatement) | |||

| Normal | Elevated | Elevated | Significant |

| Rationale for assessment (in addition to documented understanding) to provide a basis for developing responsive audit procedures | |||

| No additional rationale required. |

Consider the understanding obtained of how management develops the accounting estimate, and how this impacts our assessment of: Subjectivity –For example, the level of judgment in determining the expected outcome of selling prices and projected demand. Change –For example, changes in the entity’s environment during the period (e.g., technological developments that might make some inventory items obsolete). Susceptibility to bias or other fraud risk factors –For example, the susceptibility of the estimate to management bias (e.g., the potential for management to adopt optimistic (or pessimistic) assumptions based on their experiences, preferences and opinions). Assessed level of inherent risk –Based on consideration of likelihood (including moderate assessment of subjectivity and other inherent risk factors) and the magnitude of the potential misstatement, the assessed level of inherent risk for this accounting estimate is elevated. |

Consider the understanding obtained of how management develops the accounting estimate, and how this impacts our assessment of: Estimation uncertainty –For example, whether there is a broad range of possible outcomes for the litigation, or whether the outcome of the litigation will not become known for a long time. Subjectivity –For example, the level of judgment in assumptions about the likelihood of different litigation outcomes. Change –For example, changes in the entity’s environment during the period (e.g., new regulations that may be relevant to the litigation) Susceptibility to bias or other fraud risk factors –For example, the susceptibility of the estimate to management bias (e.g., the potential for management to adopt optimistic (or pessimistic) assumptions based on their subjective confidence in a favorable outcome). Assessed level of inherent risk –Based on a consideration of l likelihood (including moderate assessment of subjectivity and other inherent risk factors) and the magnitude of the potential misstatement, the assessed level of inherent risk for this accounting estimate is elevated |

Consider the understanding obtained of how management develops the accounting estimate, and how this impacts our assessment of: Estimation uncertainty –For example, whether there are assumptions that inherently have a high level of estimation uncertainty, such as assumptions of growth rates in a long forecast period, assumptions that are based on data that is unobservable and are therefore difficult for management to develop (e.g., fair value of assets in an inactive market), or the use of various assumptions that are interrelated (e.g., repairs and maintenance costs and asset lives). Complexity –For example, the assessed level of complexity of the discounted cash flow model used to determine value in use (e.g., number of CGUs), or in the method selected to determine fair value (e.g., specialized industry valuation techniques). Subjectivity – For example, the varying range of assumptions, including potential alternative assumptions available to management (e.g., consideration of different economic scenarios), or the approach taken to selecting assumptions for inactive or illiquid markets for the purposes of determining fair value (e.g., adjustments made to similar recent transactions). Change –For example, changes in the entity’s environment during the period (e.g., emergence of new technologies). Susceptibility to bias or other fraud risk factors –For example, the overall susceptibility of the estimate to management bias, or any indicators thereof identified (e.g., availability of a wide range of different modelling scenarios). Assessed level of inherent risk –Based on a consideration of likelihood (including high assessment of subjectivity and other inherent risk factors) and the magnitude of the potential misstatement, the assessed level of inherent risk for this accounting estimate is significant. |

Assess Control Risk

CAS Guidance

The auditor’s assessment of control risk may be done in different ways depending on preferred audit techniques or methodologies. The control risk assessment may be expressed using qualitative categories (for example, control risk assessed as maximum, moderate, minimum) or in terms of the auditor’s expectation of how effective the control(s) is in addressing the identified risk, that is, the planned reliance on the effective operation of controls. For example, if control risk is assessed as maximum, the auditor contemplates no reliance on the effective operation of controls. If control risk is assessed at less than maximum, the auditor contemplates reliance on the effective operation of controls. (CAS 540.A71)

OAG Guidance

The procedures performed to understand and evaluate the design and implementation of controls in the control activities component over management’s process for making accounting estimates (as required by CAS 540.13(i)) form the primary basis for our assessment of control risk in relation to accounting estimates.

In line with our risk assessment framework, we document our assessment of control risk through determination of the expected controls reliance for each risk of material misstatement, either at the individual risk level or at the FSLI level (see commentary on the inverse relationship of control risk and control reliance in the section Our Risk Assessment Framework in OAG Audit 5043.3). In the context of accounting estimates, our assessment of control risk is therefore documented by selecting the appropriate Expected Controls Reliance for the related risk.

Determine Audit Approach for Testing Estimate

Determine Audit Approach

CAS Requirement

As required by CAS 330, the auditor’s further audit procedures shall be responsive to the assessed risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, considering the reasons for the assessment given to those risks. The auditor’s further audit procedures shall include one or more of the following approaches (CAS 540.18):

(a) Obtaining audit evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report (see paragraph 21);

(b) Testing how management made the accounting estimate (see paragraphs 22‑27); or

(c) Developing an auditor’s point estimate or range (see paragraphs 28‑29).

The auditor’s further audit procedures shall take into account that the higher the assessed risk of material misstatement, the more persuasive the audit evidence needs to be. The auditor shall design and perform further audit procedures in a manner that is not biased towards obtaining audit evidence that may be corroborative or towards excluding audit evidence that may be contradictory.

CAS Guidance

In designing and performing further audit procedures the auditor may use any of the three testing approaches (individually or in combination) listed in paragraph 18. For example, when several assumptions are used to make an accounting estimate, the auditor may decide to use a different testing approach for each assumption tested (CAS 540.A81).

Audit evidence comprises both information that supports and corroborates management’s assertions, and any information that contradicts such assertions. Obtaining audit evidence in an unbiased manner may involve obtaining evidence from multiple sources within and outside the entity. However, the auditor is not required to perform an exhaustive search to identify all possible sources of audit evidence (CAS 540.A82).

CAS 330 requires the auditor to obtain more persuasive audit evidence the higher the auditor’s assessment of the risk. Therefore, the consideration of the nature or quantity of the audit evidence may be more important when inherent risks relating to an accounting estimate is assessed at the higher end of the spectrum of inherent risk (CAS 540.A83).

The nature, timing and extent of the auditor’s further audit procedures are affected by, for example (CAS 540.A84):

-

The assessed risks of material misstatement, which affect the persuasiveness of the audit evidence needed and influence the approach the auditor selects to audit an accounting estimate. For example, the assessed risks of material misstatement relating to the existence or valuation assertions may be lower for a straightforward accrual for bonuses that are paid to employees shortly after period end. In this situation, it may be more practical for the auditor to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence by evaluating events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report, rather than through other testing approaches.

-

The reasons for the assessed risks of material misstatement.

OAG Guidance

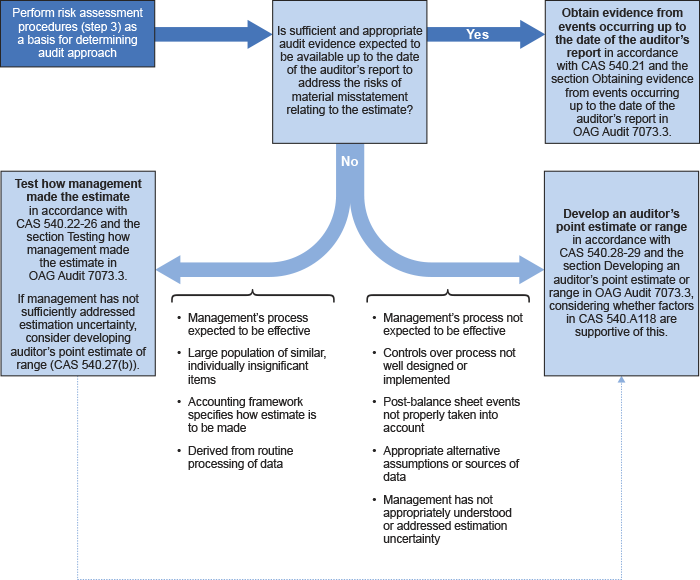

Selection of the approach or combination of approaches to testing estimates will depend on the estimate and entity-specific facts and circumstances. We need to determine an approach that is responsive to the identified inherent risks of material misstatement, including the inherent risk factors that formed the basis for our risk assessment (e.g., complexity, subjectivity, susceptibility to management bias).

For example, for a complex estimate subject to high estimation uncertainty with an outcome determined over a long time period, it is unlikely that obtaining evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report will be sufficient on its own to address the risk of material misstatement. In this scenario we would likely consider it necessary to test how management made the estimate, or to develop our own point estimate or range.

For simpler estimates resolved over a shorter time frame, we may conclude it is sufficient to obtain evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report, without the need to perform detailed audit procedures over the data, method and assumptions used by management in making the estimate.

The three methods required by the standard may be used in combination with one another if this is deemed appropriate or necessary in the circumstances. For instance, if we are testing management’s estimated provision for impairment of accounts receivable, we may plan to test management’s expected credit loss model as our primary source of evidence but may also supplement that evidence by testing cash received after the balance sheet date.

The flowchart below may be used in determining which testing approach is likely to be most effective based on the circumstances:

| Two or more of these approaches may be used in combination with one or another as deemed necessary to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence over the risks of material misstatement. |

If we decide that we cannot obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence over the estimate using one or more of these three approaches, we assess the impact on our risk assessment, audit plan and audit report and consider consulting Audit Services.

Further guidance on the application of these three approaches is set out in the following sections below:- Obtaining evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report

- Testing how management made the estimate

- Developing an auditor’s point estimate or range

Audit evidence obtained from any of the three substantive testing approaches may be supplemented by audit evidence obtained from testing the operating effectiveness of relevant controls, as appropriate. Guidance on testing controls in the audit of accounting estimates is included in the section Test Operating Effectiveness of Controls below.

Obtain Evidence from Events Occurring up to Date of Auditor’s Report

CAS Requirement

When the auditor’s further audit procedures include obtaining audit evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report, the auditor shall evaluate whether such audit evidence is sufficient and appropriate to address the risks of material misstatement relating to the accounting estimate, taking into account that changes in circumstances and other relevant conditions between the event and the measurement date may affect the relevance of such audit evidence in the context of the applicable financial reporting framework (CAS 540.21).

CAS Guidance

In some circumstances, obtaining audit evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report may provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence to address the risks of material misstatement. For example, sale of the complete inventory of a discontinued product shortly after the period end may provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence relating to the estimate of its net realizable value at the period end. In other cases, it may be necessary to use this testing approach in connection with another approach in paragraph 18 (CAS 540.A91).

For some accounting estimates, events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report are unlikely to provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence regarding the accounting estimate. For example, the conditions or events relating to some accounting estimates develop only over an extended period. Also, because of the measurement objective of fair value accounting estimates, information after the period‑end may not reflect the events or conditions existing at the balance sheet date and therefore may not be relevant to the measurement of the fair value accounting estimate (CAS 540.A92).

Even if the auditor decides not to undertake this testing approach in respect of specific accounting estimates, the auditor is required to comply with CAS 560. CAS 560 requires the auditor to perform audit procedures designed to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence that all events occurring between the date of the financial statements and the date of the auditor’s report that require adjustment of, or disclosure in, the financial statements have been identified and appropriately reflected in the financial statements. Because the measurement of many accounting estimates, other than fair value accounting estimates, usually depends on the outcome of future conditions, transactions or events, the auditor’s work under CAS 560 is particularly relevant (CAS 540.A93).

OAG Guidance

Determining whether events occurring up to the date of our report provide audit evidence regarding the accounting estimate may be an appropriate response when such events are expected to occur and provide audit evidence that confirms or contradicts the accounting estimate. Where we conclude that our substantive procedures to test an estimate will be to obtain evidence from events occurring up to the date of the auditor’s report, and this is the only method we intend to use to test the estimate, steps 4 to 6 of our 10 Step framework for auditing accounting estimates are not applicable and may be bypassed.

Test How Management Made the Estimate

CAS Requirement

When testing how management made the accounting estimate, the auditor’s further audit procedures shall include procedures, designed and performed in accordance with paragraphs 23‑26, to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence regarding the risks of material misstatement relating to (CAS 540.22):

(a) The selection and application of the methods, significant assumptions and the data used by management in making the accounting estimate; and

(b) How management selected the point estimate and developed related disclosures about estimation uncertainty.

CAS Guidance

Testing how management made the accounting estimate may be an appropriate approach when, for example (CAS 540.A94):

-

The auditor’s review of similar accounting estimates made in the prior period financial statements suggests that management’s current period process is appropriate.

-

The accounting estimate is based on a large population of items of a similar nature that individually are not significant.

-

The applicable financial reporting framework specifies how management is expected to make the accounting estimate. For example, this may be the case for an expected credit loss provision.

-

The accounting estimate is derived from the routine processing of data.

Testing how management made the accounting estimate may also be an appropriate approach when neither of the other testing approaches is practical to perform, or may be an appropriate approach in combination with one of the other testing approaches.

OAG Guidance

Consider the circumstances set out in CAS 540.A94 in determining whether testing how management made the estimate may be an appropriate testing approach.

Where these circumstances do not apply, or where our understanding of management’s information system, the results of retrospective review and other risk assessment procedures indicate that management’s process for making the estimate is not effective and is unlikely to appropriately address estimation uncertainty, we may decide that testing how management made the estimate is not a desirable approach. If we determine that management’s process does not appropriately address estimation uncertainty, we consider whether a deficiency in internal control exists and whether it should be communicated to those charged with governance, in accordance with CAS 265.

In such circumstances, we would instead develop an auditor’s point estimate or range, while following the 10 Step framework. In some circumstances we may simply consider it more efficient and effective to develop our own point estimate or range than to test management’s process, for example where our specialists/experts are able to provide industry standard assumptions or ranges that we can use to assess the reasonableness of management’s estimate.

Refer to OAG Audit 7073.4, OAG Audit 7073.5 and OAG Audit 7073.6 for guidance on testing methods, significant assumptions and data either used by management in developing the estimate and related disclosures, or used by us in developing our own point estimate or range.

Use of substantive analytical procedures to test how management made the estimate

We perform audit procedures to respond to the identified risks of material misstatement, in accordance with CAS 540.18 and CAS 330.6, which may include controls testing, substantive tests of details or substantive analytical procedures. CAS 330 and CAS 540 require that, where our approach to a significant risk consists only of substantive procedures, our audit procedures need to include tests of details, and cannot consist of substantive analytical procedures alone. Where there is higher estimation uncertainty, complexity or subjectivity, it is unlikely that substantive evidence obtained from substantive analytical procedures alone will be sufficient, and some tests of details are likely to be necessary.

As explained in CAS 520.A6, substantive analytical procedures are generally appropriate where the population comprises a large volume of transactions that tend to be predictable over time. In situations where we plan to test how management made the estimate it may be appropriate to obtain substantive evidence over how management made the estimate by performing substantive analytical procedures.

In designing and performing substantive analytical procedures to test how management made the estimate, our procedures need to meet the requirements of CAS 540 concerning management’s methods, significant assumptions and data and also need to follow the 4 step process described in OAG Audit 7033 so as to be compliant with the requirements of CAS 520.

For example, when using the four step process to perform a substantive analytical procedure to evaluate the reasonableness of depreciation expense, we would normally use management’s method (e.g., straight line depreciation), significant assumptions (e.g., useful lives) and data (e.g., cost or net book value of assets) to develop our independent expectation of the depreciation expense for the period. In this case the procedures performed to evaluate the reliability of data and develop an independent expectation would need to be adequate in nature and extent to meet the specific requirements of CAS 540 concerning significant assumptions and data. We would also need to perform procedures to assess the appropriateness of management’s method as required by CAS 540.23.

When using substantive analytical procedures designed as a reasonableness test we would expect to identify differences depending on the precision of our approach to developing an expectation. The threshold we use to determine which differences require further investigation is a matter of professional judgment and will depend upon our desired level of audit evidence from the substantive analytical procedure and other relevant factors set out in the section Considerations when defining a threshold in OAG Audit 7033.2. Where we desire a higher level of evidence and therefore determine that a high degree of precision and a very low (or zero) threshold would be needed in our substantive analytical procedures, we may determine it to be more effective and/or efficient to test how management made the estimate by performing a test of details instead of substantive analytical procedures.

We do not use substantive analytical procedures when our testing approach is to develop an auditor’s point estimate or range

Some elements of the 4 step process for performing substantive analytical procedures (described in OAG Audit 7033) may appear similar to developing an auditor’s point estimate or range, such as the development of an independent expectation to assess the reasonableness of management’s estimate.

As explained further in the section below on Develop Auditor’s Point Estimate or Range, developing an auditor’s point estimate will generally be appropriate where we believe that an estimate can be measured with a higher degree of precision because of limited variability of reasonably possible outcomes. Because of this ability to develop an auditor’s point estimate with precision, differences between our and management’s point estimates are misstatements under CAS 540.A139. If we were to attempt to design substantive analytical procedures to this level of precision, the threshold for investigation would effectively need to be zero. Therefore, we do not perform a substantive analytical procedure as a means of developing an auditor’s point estimate or range.

Use of substantive analytical procedures to consider appropriateness of significant assumptions

Regardless of whether our selected testing approach is to test how management made the estimate or develop an auditor’s point estimate or range, we may decide to use substantive analytical procedures to consider the appropriateness of a significant assumption (or assumptions) used either by management in making the estimate or that we use in developing our own point estimate or range. For example, when developing an auditor’s point estimate of contract liabilities related to warranty obligations, there may be circumstances where we consider it more effective and efficient to perform a substantive analytical procedure over a significant assumption related to actual historical repairs and replacement costs as a percentage of revenues that we intend to use in developing our point estimate. Such an approach may be appropriate where an entity has multiple products with varying contractual obligations and historic repairs and replacement cost data is not easily determinable for each product type. If we perform the substantive analytical procedure and conclude that the significant assumption is reasonable, we would use it in developing the point estimate. However, if we concluded that the significant assumption was not reasonable, then we would need to use a different significant assumption.

Develop Auditor’s Point Estimate or Range

CAS Requirement

When the auditor develops a point estimate or range to evaluate management’s point estimate and related disclosures about estimation uncertainty, including when required by paragraph 27 b), the auditor’s further audit procedures shall include procedures to evaluate whether the methods, assumptions or data used are appropriate in the context of the applicable financial reporting framework. Regardless of whether the auditor uses management’s or the auditor’s own methods, assumptions or data, these further audit procedures shall be designed and performed to address the matters in paragraphs 23‑25 (CAS 540.28).

If the auditor develops an auditor’s range, the auditor shall (CAS 540.29):

(a) Determine that the range includes only amounts that are supported by sufficient appropriate audit evidence and have been evaluated by the auditor to be reasonable in the context of the measurement objectives and other requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework; and

(b) Design and perform further audit procedures to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence regarding the assessed risks of material misstatement relating to the disclosures in the financial statements that describe the estimation uncertainty.

CAS Guidance

Developing an auditor’s point estimate or range to evaluate management’s point estimate and related disclosures about estimation uncertainty may be an appropriate approach when, for example (CAS 540.A118):

-

The auditor’s review of similar accounting estimates made in the prior period financial statements suggests that management’s current period process is not expected to be effective.

-

The entity’s controls within and over management’s process for making accounting estimates are not well designed or properly implemented.

-