Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

4024 Develop the testing strategy

Dec-2022

In This Section

Design responses to assessed risks

Testing strategies decision tree

Risks for which substantive procedures alone are not appropriate

CAS Objective

The objective of the auditor is to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence regarding the assessed risks of material misstatement, through designing and implementing appropriate responses to those risks (CAS 330.3)

Design responses to assessed risks

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall design and implement overall responses to address the assessed risks of material misstatement at the financial statement level (CAS 330.5).

The auditor shall design and perform further audit procedures whose nature, timing, and extent are based on and are responsive to the assessed risks of material misstatement at the assertion level (CAS 330.6).

In designing the further audit procedures to be performed, the auditor shall (CAS 330.7):

(a) Consider the reasons for the assessment given to the risk of material misstatement at the assertion level for each significant class of transactions, account balance, and disclosure, including:

i) The likelihood and magnitude of misstatement due to the particular characteristics of the significant class of transactions, account balance, or disclosure (that is, the inherent risk); and

ii) Whether the risk assessment takes account of controls that address the risk of material misstatement (that is, the control risk), thereby requiring the auditor to obtain audit evidence to determine whether the controls are operating effectively (that is, the auditor plans to test the operating effectiveness of controls in determining the nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures); and

(b) Obtain more persuasive audit evidence the higher the auditor’s assessment of risk.

CAS Guidance

Overall responses

Overall responses to address the assessed risks of material misstatement at the financial statement level may include (CAS 330.A1):

-

Emphasizing to the engagement team the need to maintain professional skepticism.

-

Assigning more experienced staff or those with special skills or using experts.

-

Changes to the nature, timing and extent of direction and supervision of members of the engagement team and the review of the work performed

-

Incorporating additional elements of unpredictability in the selection of further audit procedures to be performed.

-

Changes to the overall audit strategy as required by CAS 300, or planned audit procedures, and may include changes to:

- The auditor’s determination of performance materiality in accordance with CAS 320.

- The auditor’s plans to test the operating effectiveness of controls, and the persuasiveness of audit evidence needed to support the planned reliance on the operating effectiveness of the controls, particularly when deficiencies in the control environment or the entity’s monitoring activities are identified.

- The nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures. For example, it may be appropriate to perform substantive procedures at or near the date of the financial statements when the risk of material misstatement is assessed as higher.

The assessment of the risks of material misstatement at the financial statement level, and thereby the auditor’s overall responses, is affected by the auditor’s understanding of the control environment. An effective control environment may allow the auditor to have more confidence in internal control and the reliability of audit evidence generated internally within the entity and thus, for example, allow the auditor to conduct some audit procedures at an interim date rather than at the period end. Deficiencies in the control environment, however, have the opposite effect; for example, the auditor may respond to an ineffective control environment by (CAS 330.A2):

- Conducting more audit procedures as of the period end rather than at an interim date.

- Obtaining more extensive audit evidence from substantive procedures.

- Increasing the number of locations to be included in the audit scope.

Such considerations, therefore, have a significant bearing on the auditor’s general approach, for example, an emphasis on substantive procedures (substantive approach), or an approach that uses tests of controls as well as substantive procedures (combined approach) (CAS 330.A3).

Nature

CAS 315 requires that the auditor’s assessment of the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level is performed by assessing inherent risk and control risk. The auditor assesses inherent risk by assessing the likelihood and magnitude of a misstatement taking into account how, and the degree to which the inherent risk factors affect the susceptibility to misstatement of relevant assertions. The auditor’s assessed risks, including the reasons for those assessed risks, may affect both the types of audit procedures to be performed and their combination. For example, when an assessed risk is high, the auditor may confirm the completeness of the terms of a contract with the counterparty, in addition to inspecting the document. Further, certain audit procedures may be more appropriate for some assertions than others. For example, in relation to revenue, tests of controls may be most responsive to the assessed risk of material misstatement of the completeness assertion, whereas substantive procedures may be most responsive to the assessed risk of material misstatement of the occurrence assertion (CAS 330.A9).

The reasons for the assessment given to a risk are relevant in determining the nature of audit procedures. For example, if an assessed risk is lower because of the particular characteristics of a class of transactions without consideration of the related controls, then the auditor may determine that substantive analytical procedures alone provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence. On the other hand, if the assessed risk is lower because the auditor plans to test the operating effectiveness of controls, and the auditor intends to base the substantive procedures on that low assessment, then the auditor performs tests of those controls, as required by paragraph 8(a). This may be the case, for example, for a class of transactions of reasonably uniform, non‑complex characteristics that are routinely processed and controlled by the entity’s information system (CAS 330.A10).

Timing

The auditor may perform tests of controls or substantive procedures at an interim date or at the period end. The higher the risk of material misstatement, the more likely it is that the auditor may decide it is more effective to perform substantive procedures nearer to, or at, the period end rather than at an earlier date, or to perform audit procedures unannounced or at unpredictable times (for example, performing audit procedures at selected locations on an unannounced basis). This is particularly relevant when considering the response to the risks of fraud. For example, the auditor may conclude that, when the risks of intentional misstatement or manipulation have been identified, audit procedures to extend audit conclusions from interim date to the period end would not be effective (CAS 330.A11).

On the other hand, performing audit procedures before the period end may assist the auditor in identifying significant matters at an early stage of the audit, and consequently resolving them with the assistance of management or developing an effective audit approach to address such matters (CAS 330.A12).

In addition, certain audit procedures can be performed only at or after the period end, for example (CAS 330.A13):

-

Agreeing or reconciling information in the financial statements with the underlying accounting records, including agreeing or reconciling disclosures, whether such information is obtained from within or outside of the general and subsidiary ledgers;

-

Examining adjustments made during the course of preparing the financial statements; and

-

Procedures to respond to a risk that, at the period end, the entity may have entered into improper sales contracts, or transactions may not have been finalized.

Further relevant factors that influence the auditor’s consideration of when to perform audit procedures include the following (CAS 330.A14):

-

The control environment.

-

When relevant information is available (for example, electronic files may subsequently be overwritten, or procedures to be observed may occur only at certain times).

-

The nature of the risk (for example, if there is a risk of inflated revenues to meet earnings expectations by subsequent creation of false sales agreements, the auditor may wish to examine contracts available on the date of the period end).

-

The period or date to which the audit evidence relates.

-

The timing of the preparation of the financial statements, particularly for those disclosures that provide further explanation about amounts recorded in the statement of financial position, the statement of comprehensive income, the statement of changes in equity or the statement of cash flows.

Extent

The extent of an audit procedure judged necessary is determined after considering the materiality, the assessed risk, and the degree of assurance the auditor plans to obtain. When a single purpose is met by a combination of procedures, the extent of each procedure is considered separately. In general, the extent of audit procedures increases as the risk of material misstatement increases. For example, in response to the assessed risk of material misstatement due to fraud, increasing sample sizes or performing substantive analytical procedures at a more detailed level may be appropriate. However, increasing the extent of an audit procedure is effective only if the audit procedure itself is relevant to the specific risk (CAS 330.A15).

The use of computer‑assisted audit techniques (CAATs) may enable more extensive testing of electronic transactions and account files, which may be useful when the auditor decides to modify the extent of testing, for example, in responding to the risks of material misstatement due to fraud. Such techniques can be used to select sample transactions from key electronic files, to sort transactions with specific characteristics, or to test an entire population instead of a sample (CAS 330.A16).

For the audits of public sector entities, the audit mandate and any other special auditing requirements may affect the auditor’s consideration of the nature, timing and extent of further audit procedures (CAS 330.A17).

Considerations specific to smaller entities

In the case of very small entities, there may not be many controls that could be identified by the auditor, or the extent to which their existence or operation have been documented by the entity may be limited. In such cases, it may be more efficient for the auditor to perform further audit procedures that are primarily substantive procedures. In some rare cases, however, the absence of controls or of components of the system of internal control may make it impossible to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence (CAS 330.A18).

Higher Assessments of Risk

When obtaining more persuasive audit evidence because of a higher assessment of risk, the auditor may increase the quantity of the evidence, or obtain evidence that is more relevant or reliable, for example, by placing more emphasis on obtaining third party evidence or by obtaining corroborating evidence from a number of independent sources (CAS 330.A19).

OAG Guidance

We develop and apply an appropriate audit strategy in order to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements as a whole are free of material misstatement. Part of determining the audit strategy is to develop our testing strategy, which means how, in broad terms, we expect to obtain our audit evidence. Our testing strategy consists of a combination of expected controls reliance and planned substantive evidence. As described in OAG Audit 5043.3, we consider both likelihood and magnitude in assessing the risk of material misstatement for FSLI’s and document our conclusion as to the level of inherent risk using a range that we describe as a “normal,” “elevated” or “significant” level of inherent risk. It is our initial risk assessment that drives the development of our testing strategy, including the nature, timing, and extent of procedures to be performed. Through executing our testing strategy for each identified risk of material misstatement (RoMM) we intend to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to reduce audit risk to an acceptably low level. Professional judgment is required in determining the testing strategy and the corresponding amount of audit evidence that we deem necessary to address the identified risk(s) of material misstatement. The testing strategy for each identified RoMM will vary based on the level of inherent risk. For example, the testing strategies for two accounts with individual risks of material misstatement at different points along the inherent risk spectrum (e.g., normal and elevated) are likely to have a different audit response in terms of the nature, timing and extent of combinations of expected controls reliance and planned substantive evidence.

Sufficient appropriate audit evidence for each relevant assertion may be achieved either through a combination of test of controls and substantive procedures or through a single or multiple substantive procedures. Sufficient appropriate evidence is evaluated from the aggregate of evidence obtained from all testing performed over relevant assertions for a particular FSLI such that multiple testing procedures performed to achieve different levels of assurance can aggregate to sufficient appropriate evidence.

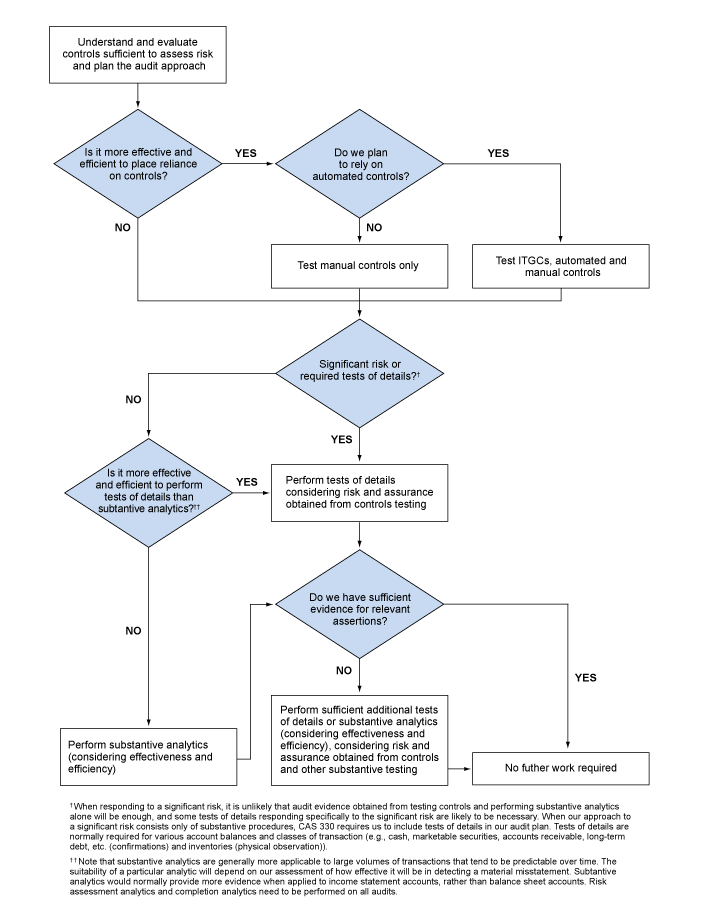

Testing strategies decision tree

OAG Guidance

In developing our testing strategy, it may be efficient and effective to place reliance on the continued effective operation of the entity’s controls and consequently take credit for the reliability of the management information that results in the entity’s external financial reporting. Once we have determined how much evidence we have from testing the operating effectiveness of controls in respect of each relevant assertion, we can determine the nature, timing and extent of our substantive testing. Considering the risk of material misstatement and the nature of the FSLI, we decide whether substantive analytics or tests of details would be the most effective and efficient way to obtain the necessary substantive evidence. Because the risk of material misstatement takes account of internal control, the extent of substantive procedures may need to be increased as a result of unsatisfactory results from tests of the operating effectiveness of controls. Alternatively, we may decide early on that controls are likely to be ineffective and we will need to obtain all or most of our evidence from substantive testing.

The diagram below shows the principal questions to consider in deciding whether our audit plan will allow us to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to address the assessed risks at an assertion level for a class of transactions, account balance, or disclosure. Although the diagram shows a linear flow, gathering and evaluating audit evidence is an iterative process and decisions on whether sufficient appropriate evidence has been obtained are taken at many different stages throughout the audit.

Decisions on whether or not we have sufficient appropriate audit evidence are based on our judgment, considering the materiality and inherent risk factors against the quality of the evidence provided, the rigor of our testing and the results of all our work. When making these decisions we consider that certain audit procedures may be more appropriate for some assertions than others.

† When responding to a significant risk, it is unlikely that audit evidence obtained from testing controls and performing substantive analytics alone will be enough, and some tests of details responding specifically to the significant risk are likely to be necessary. When our approach to a significant risk consists only of substantive procedures, CAS 330 requires us to include tests of details in our audit plan. Tests of details are normally required for various account balances and classes of transaction (e.g., cash, marketable securities, accounts receivable, long‑term debt, etc. (confirmations) and inventories (physical observation)).

† † Note that substantive analytics are generally more applicable to large volumes of transactions that tend to be predictable over time. The suitability of a particular analytic will depend on our assessment of how effective it will be in detecting a material misstatement. Substantive analytics would normally provide more evidence when applied to income statement accounts, rather than balance sheet accounts. Risk assessment analytics and completion analytics need to be performed on all audits.

Related Guidance

See OAG Audit 6050 for guidance on the development of the controls test plan.

See OAG Audit 7010 for guidance on the development of the substantive test plan.

Expected controls reliance

OAG Guidance

Expected controls reliance is the level of evidence (expressed as None, Partial or High) we expect to obtain from testing the entity’s controls for operating effectiveness, including controls evidence gathered in prior audits, if appropriate. Our decision to place reliance on controls takes into account both our assessment of control risk and view on the efficiency of obtaining evidence from controls testing compared to substantive testing. For example, when we assess control risk as low (i.e., our understanding of controls to this point indicates the entity has implemented controls that appear effective in addressing risks related to relevant financial statement assertions) and it is considered more efficient to obtain assurance from controls testing rather than performing only substantive procedures, we may consider expected controls reliance as High or Partial. Alternatively, when controls appear effective in mitigating the risk but we judge it more efficient to obtain all our evidence through substantive testing, expected controls reliance is considered as None.

High controls reliance

We plan to achieve high controls reliance when we expect to be able to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence that the control(s) in place operated effectively throughout the period of reliance and will significantly mitigate the risk to which they/it relates. Compared to a strategy of—no controls reliance, a high controls reliance strategy will significantly reduce the level of substantive evidence necessary to be satisfied that overall sufficient appropriate audit evidence has been obtained. When considering what further substantive evidence will be necessary, consider the extent to which the controls evidence has addressed all the assertions that are relevant to the risk. It may be appropriate to plan for high controls reliance for a risk even if the controls to be tested do not address P&D (where it is a relevant assertion) provided sufficient appropriate substantive evidence is obtained for the P&D assertion.

Partial controls reliance

We plan for partial controls reliance when we consider that the control (or controls) on which we intend to place reliance will only partially mitigate the risk to which they/it relates; or when the extent of our planned controls testing does not achieve a High level of assurance over the tested control(s) (i.e., the controls on which we intend to place reliance).

Examples of situations where partial controls reliance will be appropriate are as follows:

-

The number of items we test for a control upon which we plan to rely achieves a Moderate (not High) level of assurance (refer to OAG Audit 6053)

-

The RoMM relates to multiple assertions and we cannot achieve controls reliance over all of them, e.g., the risk may relate to completeness and rights and obligations; we plan to get controls reliance on Completeness and perform substantive procedures to address Rights and Obligations.

-

The risk is a composite of lower level risks and the control addresses only some of these risks, e.g., in relation to a risk of revenue being inaccurate, a control may address the pricing of goods, but not the quantity, on the invoices

-

A control may operate at an entity level and therefore is not sufficiently detailed to provide high controls reliance over transactions, e.g., business performance reviews alone may not provide high controls reliance

-

Assuming a calendar year, when the entity information system changes on 1 October, we may have controls reliance for 9 months but have to perform substantive testing for the remainder of the year.

In order that our subsequent development of the detailed testing plan responds appropriately to the relevant strategy considerations, be clear why the expected controls reliance is partial, discussing this with the team manager and/or engagement leader if necessary. Documentation of the rationales underlying the level of expected controls reliance would typically be included in related planning activities Procedure steps, but may also be included elsewhere in the audit documentation.

No controls reliance

We plan for no controls reliance when we have determined that there is a weak control environment, controls are not considered to be operating effectively for the period, or it will be more efficient and effective to obtain all audit evidence through substantive procedures.

Planned substantive evidence

OAG Guidance

Planned substantive evidence is the level of evidence (expressed as Low, Medium or High) we expect to obtain from performing substantive procedures as a whole in order to reduce audit risk to an acceptably low level. The judgment takes into account both our assessed level of inherent risk and the evidence we expect from testing controls.

We determine and document the level of planned substantive evidence for each significant FSLI where a risk of material misstatement was identified at the FSLI assertion level. If an FSLI is not determined to be significant but it is material (i.e., there is no reasonable possibility of material misstatement for the FSLI and therefore no relevant assertions are identified, but it is quantitatively material), CAS 330.18 requires us to perform substantive procedures irrespective of the assessed risk of material misstatement. For further guidance on our procedures over material but not significant FSLIs, refer to OAG Audit 5042.

For significant risks, CAS 330.21 also requires the auditor to perform substantive procedures that are specifically responsive to the risk. Therefore, if the planned substantive procedures responding to a significant risk consist solely of substantive analytical procedures, consider if those analytics are specifically responsive to the risk (i.e., address the relevant assertions and are sufficiently disaggregated to reduce the risk to an acceptably low level). For guidance on determining nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures, see OAG Audit 7020.

Consider the following guidelines when selecting the level that best reflects our planned approach to gathering substantive evidence:

Evidence Level |

Guidelines |

| Planned substantive evidence—Low | Low Planned Substantive Evidence is considered sufficient either because the level of inherent risk is assessed as normal or because of evidence expected from controls testing. Depending on the testing strategy, including which types of test will be most effective and efficient, plan to perform either substantive analytics or tests of details to obtain a low level of assurance (e.g., performing targeted testing for Low assurance). |

| Planned substantive evidence—Medium |

Medium planned substantive evidence indicates that we intend to perform substantive procedures to obtain moderate assurance, i.e., the evidence will need to be more persuasive than if the level of planned substantive evidence is Low and the level of inherent risk and the planned evidence from controls is such that the substantive evidence can be somewhat less persuasive than if the level of planned substantive evidence is High. For example:

|

| Planned substantive evidence—High |

High planned substantive evidence indicates that we plan to obtain most or all of our evidence from substantive procedures and high assurance will be needed based on the risk assessed as either an elevated or a significant risk:

|

Potential testing strategies

OAG Guidance

The table below illustrates potential testing strategy options for expected controls reliance and planned substantive evidence in response to assessed risks. These testing strategy options are consistent with common testing strategies based on CAS and OAG methodology. It shows what level of planned substantive evidence we would normally seek depending on our expected controls reliance and risk assessment. For example, when the risk is significant and the expected controls reliance is Partial, we will ordinarily plan to obtain a Medium or a High level of substantive evidence.

Crosses in the table below indicate the options that are not consistent with common testing strategies based on CAS and OAG methodology.

Assessed Inherent Risk |

Expected Controls Reliance |

Planned Substantive Evidence |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant risk | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Partial | X | Medium | High | |

| None | X | X | High | |

| Elevated risk | High | Low | Medium | X |

| Partial | Low | Medium | X | |

| None | X | Medium | High | |

| Normal risk | High | Low | X | X |

| Partial | Low | Medium | X | |

| None | Low | Medium | X | |

Professional judgment is required to determine if we will achieve the right balance between controls testing and substantive procedures in the individual circumstances of the engagement. Consider the following points that relate to testing strategy options when particular judgment may be needed to develop an appropriate response to the assessed risks.

High controls reliance and low substantive evidence: This strategy option may be effective and efficient for normal risks. When we choose to apply it to significant or elevated risks, be satisfied that our controls testing is effective enough to provide evidence that the risk is mitigated to allow for only low assurance from substantive tests to provide sufficient evidence and reduce the risk to an acceptably low level. Also, note that significant risks require substantive procedures that are specifically responsive to the risk.

Partial controls reliance and low substantive evidence: Whether this combination will be appropriate, including where we plan to test individual controls at the Moderate level of assurance (see guidance on controls testing in OAG Audit 6053), will depend on the circumstances, in particular the nature of the risk. When controls are not expected to provide strong mitigation of the risk, plan substantive procedures so that sufficient evidence is obtained in aggregate in relation to all relevant assertions. For example, if controls testing does not address completeness, include sufficient substantive tests to respond to the risk related to this assertion. Determine if low substantive evidence will be enough and whether substantive analytics will provide sufficient evidence in these circumstances, and include tests of details in the plan if appropriate. Also, note the point above on responding to a significant risk.

No controls reliance: When no reliance on controls is expected, we will normally plan to obtain high assurance from substantive tests for significant risks and moderate assurance for elevated risks. When we plan for low level of substantive evidence in case of a normal risk, determine if this is appropriate in light of our understanding of the entity, materiality and characteristics of the balance under consideration. Remember that when our response to a significant risk consists solely of substantive procedures, they shall include tests of details as required by CAS 330.21.

Risks for which substantive procedures alone are not appropriate

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall determine whether substantive procedures alone cannot provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence for any of the risks of material misstatement at the assertion level (CAS 315.33).

CAS Guidance

Due to the nature of a risk of material misstatement, and the control activities that address that risk, in some circumstances the only way to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence is to test the operating effectiveness of controls. Accordingly, there is a requirement for the auditor to identify any such risks because of the implications for the design and performance of further audit procedures in accordance with CAS 330 to address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level (CAS 315.A222).

Paragraph 26(a)(iii) also requires the identification of controls that address risks for which substantive procedures alone cannot provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence because the auditor is required, in accordance with CAS 330, to design and perform tests of such controls (CAS 315.A223).

Where routine business transactions are subject to highly automated processing with little or no manual intervention, it may not be possible to perform only substantive procedures in relation to the risk. This may be the case in circumstances where a significant amount of an entity’s information is initiated, recorded, processed, or reported only in electronic form such as in an information system that involves a high degree of integration across its IT applications. In such cases (CAS 315.A224):

-

Audit evidence may be available only in electronic form, and its sufficiency and appropriateness usually depend on the effectiveness of controls over its accuracy and completeness

-

The potential for improper initiation or alteration of information to occur and not be detected may be greater if appropriate controls are not operating effectively

|

Example: It is typically not possible to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence relating to revenue for a telecommunications entity based on substantive procedures alone. This is because the evidence of call or data activity does not exist in a form that is observable. Instead, substantial controls testing is typically performed to determine that the origination and completion of calls, and data activity is correctly captured (e.g., minutes of a call or volume of a download) and recorded correctly in the entity’s billing system. |

CAS 540 provides further guidance related to accounting estimates about risks for which substantive procedures alone do not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence. In relation to accounting estimates this may not be limited to automated processing, but may also be applicable to complex models (CAS 315.A225).

In some cases, the auditor may find it impossible to design effective substantive procedures that by themselves provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence at the assertion level. This may occur when an entity conducts its business using IT and no documentation of transactions is produced or maintained, other than through the IT system. In such cases, paragraph 8(b) requires the auditor to perform tests of controls that address the risk for which substantive procedures alone cannot provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence (CAS 330.A24).

OAG Guidance

For guidance and examples of situations where substantive procedures alone would not be appropriate refer to OAG Audit 5043.3.

We design our audit approach to such areas to include an appropriate combination of evidence from controls and substantive procedures and document the risks identified and related controls evaluated.

Related Guidance

See OAG Audit 5034 for guidance on understanding the entity’s information systems.

Sub‑Account scoping

OAG Guidance

Our preliminary identification and selection of testing populations (also referred to as “sub‑account scoping” or “lead schedule scoping”) takes place during planning after we have performed our identification of significant FSLIs and relevant assertions. It is important that we have a sufficient understanding of the entity and its environment, and of the end‑to‑end processes and controls relevant to the FSLIs for which testing is being planned, prior to identifying and selecting populations to test. We update our identification and selection of testing populations at year‑end to re‑evaluate the remaining risk of material misstatement in populations not selected for testing and to consider whether our preliminary testing selection judgments remain appropriate.

Identify sub‑accounts

We obtain a listing of amounts that comprise the significant FSLI to be tested and understand the nature of these amounts. This listing may be in the form of a trial balance, lead schedule, or other listing at a more detailed level. As with any entity‑provided information, we consider the completeness and accuracy of the listing. Once we have reviewed the listing and developed an understanding of the nature of the balances comprising the significant FSLI, we identify which sub‑accounts would represent homogeneous populations.

Generally, we define a population as a set of data from which a sample is selected and about which we plan to draw conclusions. Determining a population involves defining the appropriate and complete set of data (e.g., transactions, control instances) from which we will select our sample and about which we wish to draw conclusions. We then evaluate the homogeneity of the population in accordance with the guidance in OAG Audit 7044.1.

A homogeneous population for substantive testing purposes can be a single trial balance account, group of trial balance accounts, or a subset of a trial balance account. It may or may not be at a level below the significant FSLI identified during risk assessment. For example, an entity may have several trial balance accounts for purchase order based accruals which, depending on the underlying characteristics, may meet the criteria for being homogeneous. Alternatively, an entity may use a single trial balance account to record investments, which includes Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 investments. In this situation, the trial balance account would likely not be considered one homogeneous population based on the underlying characteristics of the investments. Accordingly, we would likely need to consider the testing population to be at a more disaggregated level than the trial balance account. Depending on how the entity has chosen to structure its chart of accounts, there may be several layers of accounts and analyses below the level of the identified in‑scope FSLI. Once homogeneous populations have been identified, we determine what, if any, testing will be performed on each of them.

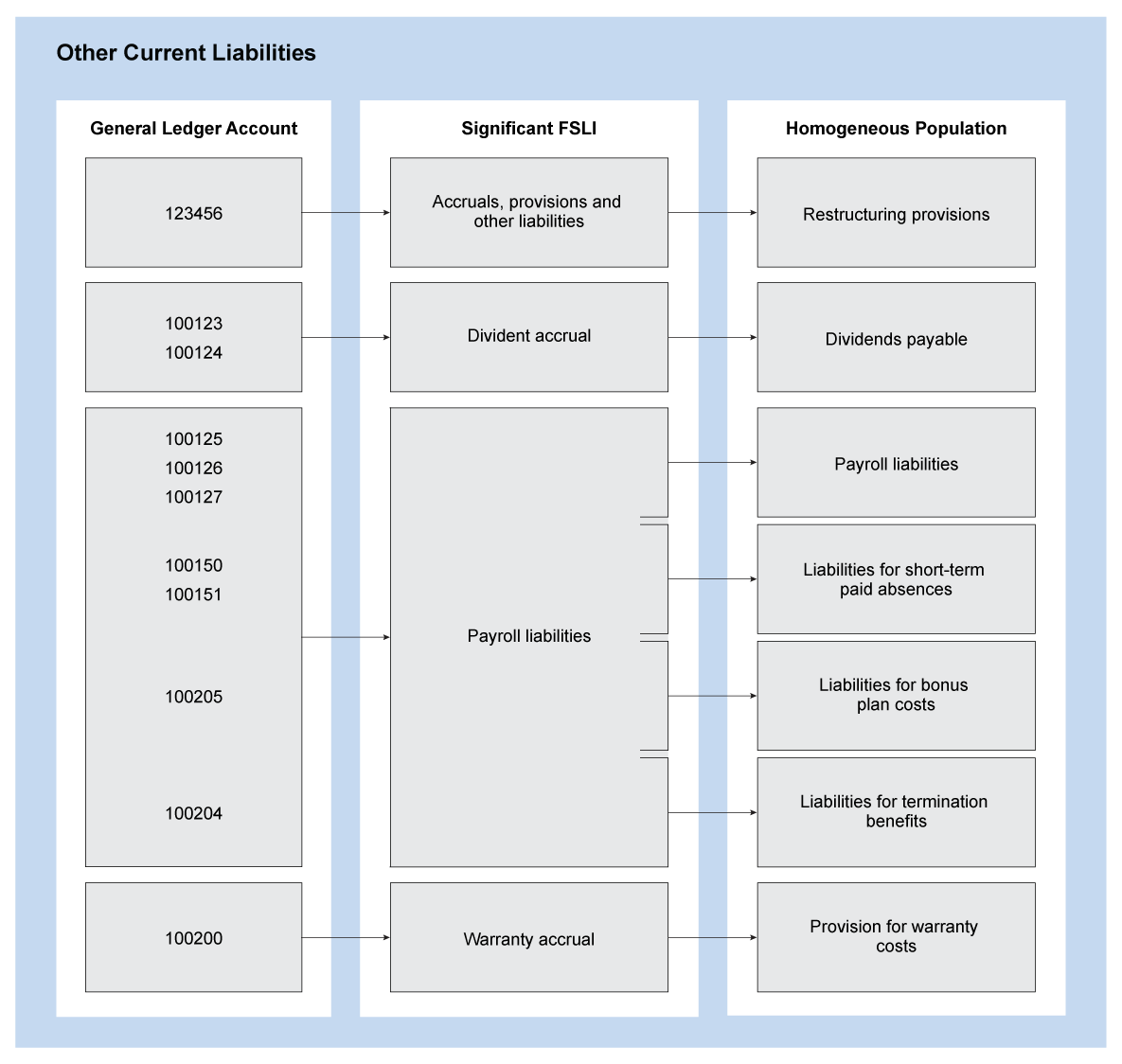

Example

Assume we are provided a detailed listing of accounts comprising the Other Current Liabilities line item presented on the entity’s balance sheet. We apply the guidance from OAG Audit 5042 and determine there are the following significant FSLIs within Other Current Liabilities—accruals, provisions and other liabilities, dividend accrual, payroll liabilities and warranty accrual. We apply the guidance from OAG Audit 7044.1 to determine which balances underlying the significant FSLIs are considered homogenous populations. As a result of those steps, we concluded the following:

Select sub‑accounts subject to testing

We consider both quantitative and qualitative risk factors to determine which homogeneous populations within a significant FSLI we are going to test. Factors to consider include, but are not limited to:

- Whether or not specific risk(s) of material misstatement exist for the population;

- Size and composition of the population;

- Volume of activity processed through the population;

- Nature, including degree of judgment, of the transactions or amounts within the population;

- Complexity of the accounting for transactions or amounts within the population;

- Degree of changes in the characteristics of the population from the prior period;

- Risk of understatement of the population or exposure to losses; and

- Susceptibility to misstatement due to error or fraud.

Note: In situations where there is one or more risk of material misstatement that is specific to a given population, we would select that population for testing because it presents a risk of material misstatement. Also note that when selecting sub‑accounts for testing, we need to consider aggregation risk and may consider using a lower quantitative threshold (e.g., percentage of performance materiality) when making the related judgements to allow for aggregation risk. Finally, note that for accounting estimates related to the sub‑accounts selected for testing we would need to perform further risk assessment procedures and develop appropriate responses in accordance with OAG Audit 7070. These additional procedures required by CAS 540 are not illustrated for the purposes of this example.

Often an effective way to inform our assessment of the above factors for a given population is through the use of appropriately designed risk assessment analytics.

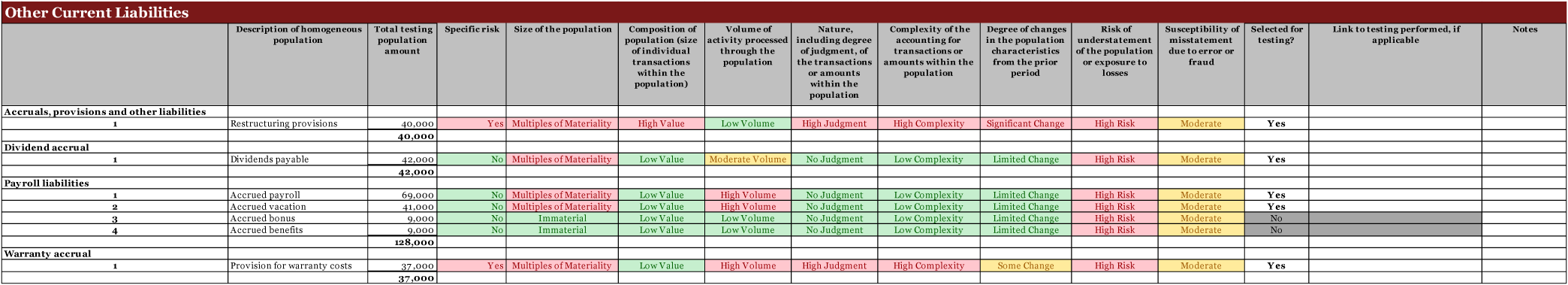

Example

Assume the same fact pattern as in the example above, relevant performance materiality of $10 million, and an identified specific risk of material misstatement related to the warranty liabilities due to the unique process and estimation uncertainty associated with the data, model and assumptions underlying the estimated liabilities. Assume the risks identified for the remaining testing populations within the other significant FSLIs were similar and no other specific risks were identified. We identified a specific risk for the accuracy of the restructuring provision as a result of the impact of the inherent risk factor of uncertainty. We considered the factors listed above and determined the following sub-accounts would be selected for testing (amounts are in millions of CND$):

*Note that the example is provided for illustrative purposes only and does not aim to address all specific engagement circumstances that may need to be taken into account. Our documentation needs to reflect the specific engagement circumstances and explain the rationale for the judgments made.

Consider the remaining risk of material misstatement in sub‑accounts not selected for testing

Once we have selected sub‑accounts to test, we stand back and consider the overall sufficiency of our audit evidence for the significant FSLI. There may be sub‑accounts within the significant FSLI that were not selected for testing. The remaining risks in these unselected sub‑accounts are considered both individually and in the aggregate before finalizing our decisions regarding which sub‑accounts to test.

There is no minimum required coverage of sub‑accounts selected for testing within a significant FSLI. We are also not required to reduce the aggregate value of sub‑accounts not selected for testing to below performance materiality.

Factors to consider when evaluating the sufficiency of evidence obtained after selecting populations for testing include, but are not limited to:

Factor |

Consideration |

| Materiality of aggregated populations not selected for testing | Significance of potential misstatements increases as the materiality of the aggregated unselected populations increases |

| Number of populations not subject to substantive testing |

The greater the number of populations not selected for testing, the less aggregation risk as the amounts are dispersed amongst different populations |

| Concentration of risk |

The level of judgment to evaluate the sufficiency of evidence increases as the concentration of risk increases (e.g., the more populations not selected for testing, the greater the possibility of a material misstatement going undetected by our procedures) |

| Nature of the significant FSLI | The greater the risk associated with the significant FSLI (including the risk of understatement, as with liabilities), the more persuasive the evidence generally needed and the more likely we are to select additional populations for testing within that FSLI |

| Nature of the populations not selected for testing | The greater the risk associated with the populations not selected for testing, the more likely some testing of those populations will need to be performed to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence for the significant FSLI (Note: each individual population that presents at least one specific risk of material misstatement would need to be selected for testing, as it presents a risk of material misstatement on its own and would generally be considered a separate significant FSLI) |

| Change within the population not selected for testing | The more significant the change (e.g., change in nature, volume, concentration of risk) in the population during the period (including situations where the population is new), the more likely we will decide to perform testing over such population |

Additionally, we consider the results of other procedures performed, as these can inform our scoping decisions, including:

- Our risk assessment procedures, including analytical procedures;

- Procedures we perform on other related FSLIs and other populations within the FSLI;

- Reported nature, timing, extent and results of procedures performed by internal audit; and

- Procedures we performed in the prior year.

These procedures may identify specific risks of material misstatement, indicating such populations need to be tested. For example, if numerous errors or audit adjustments were identified in the testing of selected balances, or if there were relevant findings from internal audit procedures, we consider how this information impacts our evaluation of whether to perform testing of populations not initially selected for testing.

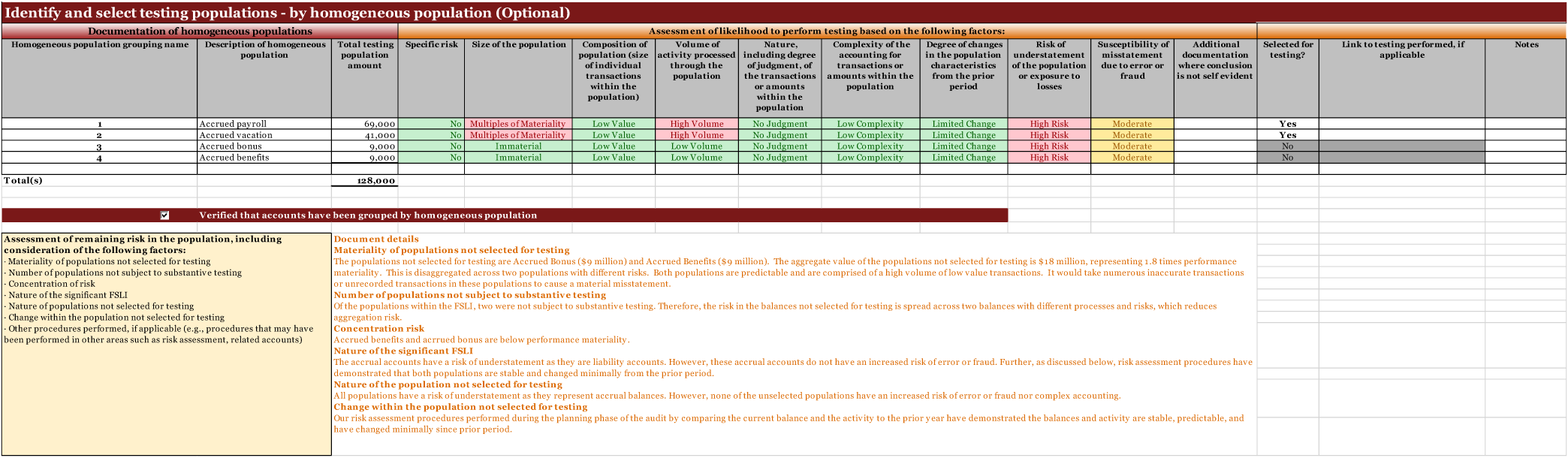

Documentation

We may use the optional ‘Sub-Account Scoping Template’ to document the conclusions with respect to the selection of populations to test. The table below demonstrates how the engagement team used the optional template to document the conclusion on the populations to test within the Payroll Liabilities significant FSLI, as outlined in the example above.