Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

7043.1 A five step approach to performing accept-reject testing

Sep-2022

In This Section

Step 1: Determine and document the assertion(s) being tested

Step 4: Determine number of items to test and select items

OAG Guidance

Determine the assertion being tested. Accept-reject testing or attribute testing is used only for testing attributes, and not monetary amounts. For other assertions, accept-reject testing may be appropriate. It is not appropriate to test the valuation and accuracy assertions in relation to monetary values. (Note that we may use accept-reject testing to obtain evidence over accuracy of revenues in certain circumstances. Refer to guidance in OAG Audit 7011.1.)

Related Guidance

See guidance on when it is appropriate to use accept-reject testing at OAG Audit 7043.

OAG Guidance

Define what we are going to test and verify it is the appropriate population to select from to address the assertion we want to test. In defining the test unit, we need to consider which testing unit leads to the most effective and efficient testing. For example, if we want to test that all shipping documents are recorded, it would not be appropriate to select from a list of recorded documents. Also assess whether the population we select from is complete.

OAG Guidance

Exceptions exist when test results for a particular item are outside what is considered acceptable. It is essential to have a clear definition of what constitutes an exception prior to executing accept-reject testing. The appropriate exception definition will depend on the test objective and may include an allowance for inconsequential differences.

Inconsequential differences would not be considered to be an exception for purposes of the test. However, define an inconsequential difference with care and before the commencement of testing, so as to avoid inadvertently accepting a test result that shall be rejected.

For example, in testing a date attribute, an exception may be defined as an unsupported time difference greater than one day or one week, e.g., a date of hire for a pension, depending on the circumstances, where the impact of the difference would be inconsequential to the financial statements. In some cases, like testing sales cut‑off, a difference of one day would likely be unacceptable.

OAG Guidance

Populations of 200 Items or More

When applying accept-reject testing to populations of 200 or more items apply the sample sizes** as shown in the table below.

| Desired level of evidence* | Number of items to test** | ||

| No exceptions tolerated | 1 exception tolerated | 2 exceptions tolerated | |

| Low | 16 | 32 | 52 |

| Moderate | 30 | 55 | 80 |

| High | 55 | 85 | 115 |

*The levels of evidence translate to roughly 45–50 %, 73–80 %, and 90–95 % confidence levels respectively for low, moderate, and high levels of evidence. A 45–50 % confidence level is acceptable when low evidence only is required from the accept-reject testing because other audit procedures relating to the assertions have been performed, that when combined with the accept-reject testing provide a sufficient level of assurance overall.

**While accept-reject testing is an acceptable and efficient approach for testing transaction or population attributes, statistical attribute sampling can also be used. See the attribute sampling model within IDEA if statistical attribute sampling is to be used.

The more important the attribute being tested using accept-reject testing and the more assurance required the more items we test and the lower the acceptable error rate. However, just because we can tolerate an error based on the table above does not mean it is appropriate to tolerate any errors. The nature of the testing is relevant in determining the level of exceptions that can be tolerated. For example, we may not be able to tolerate any exceptions when testing key reconciliations such as bank reconciliations. An identified difference that meets the pre‑determined definition of an inconsequential difference would typically not be considered to be an exception for purposes of evaluating the results of testing.

Populations of 200 or Less Items

When applying accept-reject testing to populations fewer than 200 items the sample sizes as shown in the table below are applied. These sample sizes are minimum sample sizes to obtain low assurance. If a higher level of assurance is required test more than the minimum number of items. Judgment is required to determine the appropriate sample size. In such instances consider consulting with the Internal Specialist— Research and Quantitative Analysis.

| Population range | Number of items to test |

| Between 100 and 199 items | 10 |

| Between 50 and 99 items | 5 |

| Between 20 and 49 items | 3 |

| Fewer than 20 items | 2 |

When planning to test 10 or fewer items (i.e., for populations of 200 and less items) no exceptions can be accepted. Sample sizes will need to be increased if any exceptions are tolerated when testing small populations. In such instances, consider consulting with the Internal Specialist— Research and Quantitative Analysis.

Generally use a haphazard or random selection approach when applying accept-reject testing.

Related Guidance

See guidance on sample selection techniques at OAG Audit 7044.

OAG Guidance

After the accept-reject plan has been designed and the items to be tested have been selected, the planned audit tests are applied to each of the selected items. It is not appropriate to reduce initially established sample sizes if early test results find no misstatements or if results appear better than expected. For example, if the plan is to test 52 items, accepting 2 exceptions, then testing needs to be applied to all 52 items. It is not appropriate to test 16 with no exceptions, stop testing and determine the test objectives have been met. Even if no exceptions are observed in early testing, complete the planned level of testing to obtain the desired level of evidence.

Whenever exceptions are found, evaluate and understand the nature and cause of the exceptions. If the exception rate is greater than we planned to tolerate, either reject the test or expand the testing if it is determined additional testing may provide sufficient evidence. In some cases where it is originally planned to tolerate zero exceptions, expanded testing does not make sense because the attribute or account or assertion being testing would not be acceptable with any exceptions. For example, when accept-reject testing is used for testing mathematical accuracy, the test results are only acceptable if no mathematical errors are found. If mathematical errors are found, we ordinarily reject the accuracy of the listing and ask the client to re‑total and then we would re‑perform the test. In other cases, we may determine that additional testing can meet the test objectives.

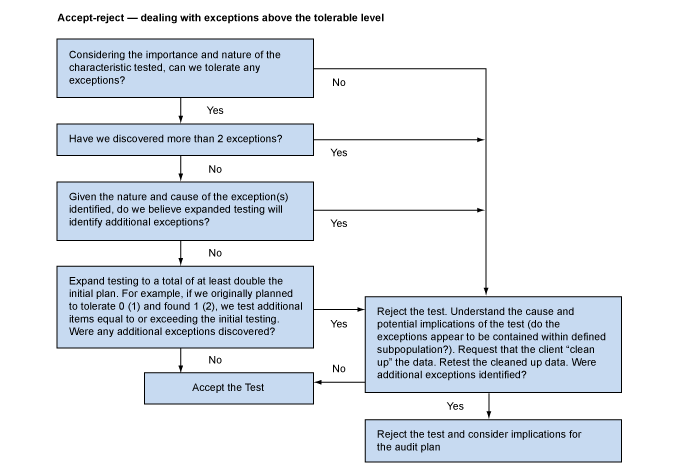

Expanding the Scope of Testing vs. Rejecting the Test

When the number of exceptions is more than we can accept, we reject the test. Furthermore, whenever we find more than two exceptions, we reject the test. To the extent we have two or less exceptions, we understand and evaluate the nature and cause of the exception(s). In doing so we consider the likelihood that we will find additional exceptions. If we are satisfied that it is reasonable to expect no further exceptions in our testing, we may expand the test. If we are not satisfied, then we reject the test. We also consider whether the exception(s) identified can be contained, for example, to a particular inventory count team. In this case, we can focus our response on this area. Determining whether it is appropriate to expand our test is a matter of professional judgment. Our understanding and evaluation of the nature and cause of exception(s) and the basis for our conclusions regarding whether we reject the test or expand testing need to be documented within our audit file.

If after careful evaluation of the exception(s), we determine it is appropriate to expand testing, we then need to determine the number of additional items to test. When we expand testing we do not simply add the increment from the table above, rather we at least double our initial testing level. For example, if we were testing to achieve a moderate level of evidence and planned to tolerate zero exceptions and we find one exception, we may decide to increase our tolerance for errors from zero to one if we believe no additional exceptions would occur and we could achieve our desired moderate level of assurance by performing additional testing. However, we would not just add the incremental number of items to increase testing from 30 to 55. Rather we at least double our initial testing level so we would test at least an additional 30 items (60 total) and accept the test if we find no additional exceptions. The same approach would apply for other levels of desired evidence as well. For example, if we planned to tolerate zero exceptions and we find 1 exception in 30 items tested, we would test an additional 30 items (60 total) and accept the test if we find no additional exceptions. If we planned to tolerate 1 exception and we found 2 in the 55 items originally selected (moderate evidence), we would test an additional 55 items (110 total) and accept the test if we find no additional items.

In situations where we planned to tolerate zero exceptions and we find two exceptions, the minimum additional sample sizes are calculated considering the larger of doubling the original sample size or doubling the number of items to test assuming one exception was originally tolerated. For example, if we were testing to achieve a moderate level of evidence and we planned to tolerate 0 exceptions and we find 2 exceptions in 30 items tested, we would need to test at least an additional 80 items (110 in total). This would represent a double testing level for situations when we can tolerate 1 exception (i.e., 80 = 55 X 2 –30 (originally tested)). Notwithstanding the option to expand testing, carefully consider and document our rationale for concluding it was appropriate to expand the sample size and conduct further testing in a situation where we were originally willing to tolerate zero exceptions and instead experienced two exceptions.

When a test is rejected attempt to quantify the error and then discuss the cause and potential impact with the entity, and ask the entity to correct the situation. After the entity corrects the identified problem, we can retest the population and, if we find no exceptions, we accept the test results.

Once the entity has corrected the problem, we would expect zero exceptions. Where the entity refuses to correct the problem, consult in accordance with OAG Audit 3081.

Practice Aid

The following flowchart can be used to assist in dealing with exceptions above the tolerable level:

OAG Guidance

When applying accept-reject testing, we are strongly encouraged to use the Accept-Reject Test Template and the relevant Standard Documentation Sheet within the Menu tab of the Test of Details template.