Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

5504 Risk Assessment and Related Activities

Sep-2022

In This Section

Inquiries of management and others

Inquiries of those charged with governance

Results of analytical procedures

Consideration of other information

CAS Requirement

In accordance with CAS 200, the auditor shall maintain professional skepticism throughout the audit, recognizing the possibility that a material misstatement due to fraud could exist, notwithstanding the auditor’s past experience of the honesty and integrity of the entity’s management and those charged with governance (CAS 240.13).

Unless the auditor has reason to believe the contrary, the auditor may accept records and documents as genuine. If conditions identified during the audit cause the auditor to believe that a document may not be authentic or those terms in a document have been modified but not disclosed to the auditor, the auditor shall investigate further (CAS 240.14).

Where responses to inquiries of management or those charged with governance are inconsistent, the auditor shall investigate the inconsistencies (CAS 240.15).

CAS Guidance

Maintaining professional skepticism requires an ongoing questioning of whether the information and audit evidence obtained suggests that a material misstatement due to fraud may exist. It includes considering the reliability of the information to be used as audit evidence and identified controls in the control activities component, if any, over its preparation and maintenance. Due to the characteristics of fraud, the auditor’s professional skepticism is particularly important when considering the risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.A8).

Although the auditor cannot be expected to disregard past experience of the honesty and integrity of the entity’s management and those charged with governance, the auditor’s professional skepticism is particularly important in considering the risks of material misstatement due to fraud because there may have been changes in circumstances (CAS 240.A9).

An audit performed in accordance with CASs rarely involves the authentication of documents, nor is the auditor trained as or expected to be an expert in such authentication. However, when the auditor identifies conditions that cause the auditor to believe that a document may not be authentic or that terms in a document have been modified but not disclosed to the auditor, possible procedures to investigate further may include (CAS 240.A10):

- Confirming directly with the third party.

- Using the work of an expert to assess the document’s authenticity.

CAS Requirement

When performing risk assessment procedures and related activities to obtain an understanding of the entity and its environment, the applicable financial reporting framework and the entity’s system of internal control, required by CAS 315, the auditor shall perform the procedures in paragraphs 18-25 to obtain information for use in identifying the risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.17).

Paragraphs 18-25 are addressed in the following OAG Annual Audit Manual blocks:

- Inquiries of management and others (CAS 240.18‑19)

- Inquiries of the internal audit function (CAS 240.20)

- Inquiries of those charged with governance(CAS 240.21‑22)

- Results of analytical procedures (CAS 240.23)

- Consideration of other information (CAS 240.24)

- Evaluation of fraud risk factors (CAS 240.25)

The auditor shall include the following in the audit documentation of the identification and the assessment of the risks of material misstatement required by CAS 315 (CAS 240.45):

-

The significant decisions reached during the discussion among the engagement team regarding the susceptibility of the entity’s financial statements to material misstatement due to fraud;

-

The identified and assessed risks of material misstatement due to fraud at the financial statement level and at the assertion level; and

-

Identified controls in the control activities component that address assessed risks of material misstatement due to fraud.

OAG Policy

Any suspected fraud or other irregularity shall be documented as a significant matter. [Oct‑2012]

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall make inquiries of management regarding (CAS 240.18):

a) management’s assessment of the risk that the financial statements may be materially misstated due to fraud, including the nature, extent and frequency of such assessments;

b) management’s process for identifying and responding to the risks of fraud in the entity, including any specific risks of fraud that management has identified or that have been brought to its attention, or classes of transactions, account balances, or disclosures for which a risk of fraud is likely to exist;

c) management’s communication, if any, to those charged with governance regarding its processes for identifying and responding to the risks of fraud in the entity; and

d) management’s communication, if any, to employees regarding its views on business practices and ethical behavior.

The auditor shall make inquiries of management, and others within the entity as appropriate, to determine whether they have knowledge of any actual, suspected or alleged fraud affecting the entity (CAS 240.19).

CAS Guidance

Management’s Assessment of the Risk of Material Misstatement Due to Fraud

Management accepts responsibility for the entity’s internal control and for the preparation of the entity’s financial statements. Accordingly, it is appropriate for the auditor to make inquiries of management regarding management’s own assessment of the risk of fraud and the controls in place to prevent and detect it. The nature, extent and frequency of management’s assessment of such risk and controls may vary from entity to entity. In some entities, management may make detailed assessments on an annual basis or as part of continuous monitoring. In other entities, management’s assessment may be less structured and less frequent. The nature, extent and frequency of management’s assessment are relevant to the auditor’s understanding of the entity’s control environment. For example, the fact that management has not made an assessment of the risk of fraud may in some circumstances be indicative of the lack of importance that management places on internal control (CAS 240.A13).

Management’s Process for Identifying and Responding to the Risks of Fraud

In the case of entities with multiple locations management’s processes may include different levels of monitoring of operating locations, or business segments. Management may also have identified particular operating locations or business segments for which a risk of fraud may be more likely to exist (CAS 240.A15).

Inquiry of Management and Others within the Entity

The auditor’s inquiries of management may provide useful information concerning the risks of material misstatements in the financial statements resulting from employee fraud. However, such inquiries are unlikely to provide useful information regarding the risks of material misstatement in the financial statements resulting from management fraud. Making inquiries of others within the entity may provide individuals with an opportunity to convey information to the auditor that may not otherwise be communicated (CAS 240.A16).

Examples of others within the entity to whom the auditor may direct inquiries about the existence or suspicion of fraud include (CAS 240.A17):

-

Operating personnel not directly involved in the financial reporting process.

-

Employees with different levels of authority.

-

Employees involved in initiating, processing or recording complex or unusual transactions and those who supervise or monitor such employees.

-

In-house legal counsel.

-

Chief ethics officer or equivalent person.

-

The person or persons charged with dealing with allegations of fraud.

Management is often in the best position to perpetrate fraud. Accordingly, when evaluating management’s responses to inquiries with an attitude of professional skepticism, the auditor may judge it necessary to corroborate responses to inquiries with other information (CAS 240.A18).

In some entities, particularly smaller entities, the focus of management’s assessment may be on the risks of employee fraud or misappropriation of assets. (CAS 240.A14)

OAG Guidance

Our inquiries of management and others within the entity are important because fraud often is uncovered through information received in response to inquiries.

See below for ideas to frame the inquiries of management, both risks and management’s responses to risk.

Fraud Risk—Audit Committee Inquiries, Fraud Risk—Internal Audit Inquiries and Fraud Risk—Management Inquiries are three templates designed to help plan and document inquiries.

Generally, these inquiries are directed to the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and financial controller, as well as to management of significant components and leaders of major operational and support services. Consider directing inquiries to a cross‑section of management, in terms of organizational responsibility, level of position held, and geographic location. These inquiries are documented in the procedure “Understand entity and environment” within the program “Understand the Entity and Environment.”

If management is required by law or local standards to report incidences of fraud to the Audit Committee and/or the external auditors, review all such communications, and determine if we believe management’s processes for deterrence and detection support the veracity of their reporting process.

When gaining an understanding of management’s fraud risk assessment and related controls, consider the linkage with assessment of internal control components. The controls identified as part of our fraud risk assessment would mirror the controls identified as part of management’s risk assessment. For further information regarding assessing management’s anti‑fraud programs and controls, refer to OAG Audit 5505.

We use professional judgment to determine the others within the entity to whom inquiries are directed and the extent of those inquiries, considering whether they might be able to provide information that will be helpful to us in identifying fraud risks.

If any allegations of fraud or inappropriate behavior have been made during the period to those responsible for whistle‑blower or ethics hotlines, etc., and employees making such allegations can be identified, then our inquiries include these personnel.

General Subject Areas

The following are subject areas to consider when making inquiries of management, Audit Committee, internal audit, and others within the entity:

-

Fraud history at the company.

-

Management accountability for fraud.

-

Board of Directors and or Audit Committee oversight.

- Fraud risk assessment process.

- Investigation and remediation.

- Monitoring of the whistleblower hotline and other complaints.

- Use of internal audit for fraud auditing.

- Actions taken to address the potential for management override of controls.

- Interaction with management on the accounting for significant or unusual transactions.

-

Fraud control environment.

-

Programs and controls.

-

Incentives and pressures.

-

Employee and third party integrity diligence.

-

Communication of the Code of Conduct/ Ethics.

-

Communication of the availability of the whistleblower hotline.

-

Commitment to prevent and detect.

-

Fraud risk assessment process.

- Personnel involved in process.

- Locations considered.

- Consideration of fraud risks relating to:

- Revenue recognition.

- Accounts subject to estimation.

- Significant unusual transactions.

- Related party transactions.

- Intercompany and suspense account activity.

- Management override of controls (via journal entries).

- Information systems.

- Misappropriation of assets.

- Unauthorized receipts and expenditures.

- Disclosures.

-

Linkage of identified fraud risks to controls.

-

Controls over identified fraud risks.

-

Employee and third party integrity diligence.

-

Information system and communication.

-

Monitoring and auditing systems.

-

Investigation and remediation.

-

Commitment to prevent and detect fraud.

-

Changes in procedures.

-

Changes in requests of supervisors.

-

Comfort level in performing daily activities.

-

Knowledge of fraud.

-

Process to respond to internal or external allegations of fraud affecting the entity.

-

Knowledge of any unusual transactions or transactions recorded in a manner outside the norm.

-

Inquiry of general counsel with respect to alleged or actual frauds.

-

Inquiry of the Chief Compliance Officer.

Below are example inquiries that can be directed to management and others regarding fraud. Document the date, location, scope and participants involved in each inquiry.

|

Management Inquiries (to be asked of the CEO, CFO, and Financial Controller, and other management depending upon the structure of the entity) Each engagement team needs to determine the appropriate questions to ask of management and the mode of inquiry (e.g., formal versus informal discussion). For example:

Programs and controls may include

Note: When addressing questions to gain an understanding of management’s fraud risk assessment and related controls, consider the linkage with assessment of internal control components. Inquiries of Others in the OrganizationUsing professional judgment, determine whether to direct inquiries about the existence or suspicion of inappropriate activities to others. The following are example questions that could be asked in addition to the above inquiries, as determined appropriate by the engagement team:

|

CAS Requirement

For those entities that have an internal audit function, the auditor shall make inquiries of appropriate individuals within the function to determine whether they have knowledge of any actual, suspected or alleged fraud affecting the entity, and to obtain its views about the risks of fraud (CAS 240.20).

CAS Guidance

CAS 315 and CAS 610 establish requirements and provide guidance relevant to audits of those entities that have an internal audit function. In carrying out the requirements of those CASs in the context of fraud, the auditor may inquire about specific activities of the function including, for example (CAS 240.A19):

- The procedures performed, if any, by the internal audit function during the year to detect fraud.

- Whether management has satisfactorily responded to any findings resulting from those procedures.

OAG Guidance

Below are example inquiries that can be directed to internal auditors regarding fraud.

Internal Audit Inquiries

-

What are your views regarding the risk of fraud?

-

What specific Internal Audit procedures have been performed to prevent, deter, or detect fraud?

-

Are you aware of any instances of fraud, whether actual, suspected or alleged?

-

Has management satisfactorily responded to internal audit findings and recommendations throughout the year, regarding the risk or detection of fraud?

-

Have you conducted any specific reviews at the request of management?

See related guidance on internal audit at OAG Audit 6030.

CAS Requirement

Unless all of those charged with governance are involved in managing the entity, the auditor shall obtain an understanding of how those charged with governance exercise oversight of management’s processes for identifying and responding to the risks of fraud in the entity and the controls that management has established to mitigate these risks (CAS 240.21).

Unless all of those charged with governance are involved in managing the entity, the auditor shall make inquiries of those charged with governance to determine whether they have knowledge of any actual, suspected or alleged fraud affecting the entity. These inquiries are made in part to corroborate the responses to the inquiries of management (CAS 240.22).

CAS Guidance

Obtaining an Understanding of Oversight Exercised by Those Charged With Governance

Those charged with governance of an entity oversee the entity’s systems for monitoring risk, financial control and compliance with the law. In many countries, corporate governance practices are well developed and those charged with governance play an active role in oversight of the entity’s assessment of the risks of fraud and the controls that address such risks. Since the responsibilities of those charged with governance and management may vary by entity and by country, it is important that the auditor understands their respective responsibilities to enable the auditor to obtain an understanding of the oversight exercised by the appropriate individuals (CAS 240.A20).

CAS 260 discusses with whom the auditor communicates when the entity’s governance structure is not well defined.

An understanding of the oversight exercised by those charged with governance may provide insights regarding the susceptibility of the entity to management fraud, the adequacy of controls that address risks of fraud, and the competency and integrity of management. The auditor may obtain this understanding in a number of ways, such as by attending meetings where such discussions take place, reading the minutes from such meetings or making inquiries of those charged with governance (CAS 240.A21).

OAG Guidance

See related guidance on communications with those charged with governance at OAG Audit 2210.

Example Inquiries for those charged with Governance

-

What are your views about the risk of fraud?

-

Are you aware of any fraud that either has been perpetrated or is suspected?

-

How do you ensure that the financial statements and other materials submitted to the Board are free of management manipulation and override?

-

What incentives and pressures do you perceive to be on management and how are the related fraud risks managed?

-

How do you exercise oversight over activities regarding the risks of fraud and the programmes and controls established to mitigate risks?

-

What protocols have you established with management to be informed of all fraud, material or not, that involve management or other employees that have a significant role in internal controls?

-

Were any matters relating to fraud reported to the Audit Committee, where we were not present, during the year? What action did management and the Audit Committee take?

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall evaluate whether unusual or unexpected relationships that have been identified in performing analytical procedures, including those related to revenue accounts, may indicate risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.23).

OAG Guidance

Disaggregated analytics represent a powerful audit tool. They may be capable of revealing details including specific indicators of fraud that may not be seen when performing analytics at a higher level. For similar reasons, it is also helpful to analyse costs and margins on a disaggregated basis wherever possible. The level of disaggregated analytics is consistent with the engagement team’s assessment of risk of error or at a lower level if identified risk of fraud exists.

See our risk assessment analytics guide at OAG Audit 5012.2.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall consider whether other information obtained by the auditor indicates risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.24).

CAS Guidance

In addition to information obtained from applying analytical procedures, other information obtained about the entity and its environment, the applicable financial reporting framework and the entity’s system of internal control may be helpful in identifying the risks of material misstatement due to fraud. The discussion among team members may provide information that is helpful in identifying such risks. In addition, information obtained from the auditor’s client acceptance and retention processes, and experience gained on other engagements performed for the entity, for example engagements to review interim financial information, may be relevant in the identification of the risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.A23).

OAG Guidance

Consideration of fraud risks relating to fraudulent financial reporting begins at the client acceptance and continuance stage through the use of the Acceptance & Continuance process. This includes common fraud risk factors to be considered, specifically relating to fraudulent financial reporting.

See related guidance on A&C procedures at OAG Audit 3010.

Other information that might be helpful in identifying fraud risk includes:

-

Consideration of financial statement line items that may be particularly subject to fraud risk. For example, because they involve a high degree of management judgment and subjectivity leading to a risk of fraudulent financial reporting (such as estimation of liabilities resulting from a restructuring) or they are susceptible to misappropriation.

-

We may consider allegations of fraud and misconduct received by the entity when considering material fraud risks on our engagements. These allegations generally are included in the entity’s whistleblower and investigations log.

Information gathered about the incentives/pressures facing management. For example, develop an inventory of management’s performance‑related earnings or similar arrangements, including identifying the levels of performance that trigger them. The consideration of other information is performed in the procedure “Other risk assessment procedures”.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall evaluate whether the information obtained from the other risk assessment procedures and related activities performed indicates that one or more fraud risk factors are present. While fraud risk factors may not necessarily indicate the existence of fraud, they have often been present in circumstances where frauds have occurred and therefore may indicate risks of material misstatement due to fraud (CAS 240.25).

CAS Guidance

The fact that fraud is usually concealed can make it very difficult to detect. Nevertheless, the auditor may identify events or conditions that indicate an incentive or pressure to commit fraud or provide an opportunity to commit fraud (fraud risk factors). For example (CAS 240.A24):

-

The need to meet expectations of third parties to obtain additional equity financing may create pressure to commit fraud;

-

The granting of significant bonuses if unrealistic profit targets are met may create an incentive to commit fraud; and

-

A control environment that is not effective may create an opportunity to commit fraud.

Fraud risk factors cannot easily be ranked in order of importance. The significance of fraud risk factors varies widely. Some of these factors will be present in entities where the specific conditions do not present risks of material misstatement. Accordingly, the determination of whether a fraud risk factor is present and whether it is to be considered in assessing the risks of material misstatement of the financial statements due to fraud requires the exercise of professional judgment (CAS 240.A25).

Examples of fraud risk factors related to fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets are presented in Appendix 1 [This appendix is included as section 5502]. These illustrative risk factors are classified based on the three conditions that are generally present when fraud exists (CAS 240.A26):

- An incentive or pressure to commit fraud;

- A perceived opportunity to commit fraud; and

- An ability to rationalize the fraudulent action.

Fraud risk factors may relate to incentives, pressures or opportunities that arise from conditions that create susceptibility to misstatement, before consideration of controls. Fraud risk factors, which include intentional management bias, are, insofar as they affect inherent risk, inherent risk factors. Fraud risk factors may also relate to conditions within the entity’s system of internal control that provide opportunity to commit fraud or that may affect management’s attitude or ability to rationalize fraudulent actions. Fraud risk factors reflective of an attitude that permits rationalization of the fraudulent action may not be susceptible to observation by the auditor. Nevertheless, the auditor may become aware of the existence of such information through, for example, the required understanding of the entity’s control environment. Although the fraud risk factors described in Appendix 1 [This appendix is included as section 5502] cover a broad range of situations that may be faced by auditors, they are only examples and other risk factors may exist.

The size, complexity, and ownership characteristics of the entity have a significant influence on the consideration of relevant fraud risk factors. For example, in the case of a large entity, there may be factors that generally constrain improper conduct by management, such as (CAS 240.A27):

- Effective oversight by those charged with governance.

- An effective internal audit function.

- The existence and enforcement of a written code of conduct.

Furthermore, fraud risk factors considered at a business segment operating level may provide different insights when compared with those obtained when considered at an entity‑wide level.

OAG Guidance

In identifying fraud risks, it is helpful to consider the information we have gathered in the context of incentives/pressures, opportunities and rationalization/attitudes. However, do not assume that all three conditions need to be observed or evident before concluding that there are identified risks. In fact, risk factors reflective of employee rationalization or attitudes are generally not susceptible to observation.

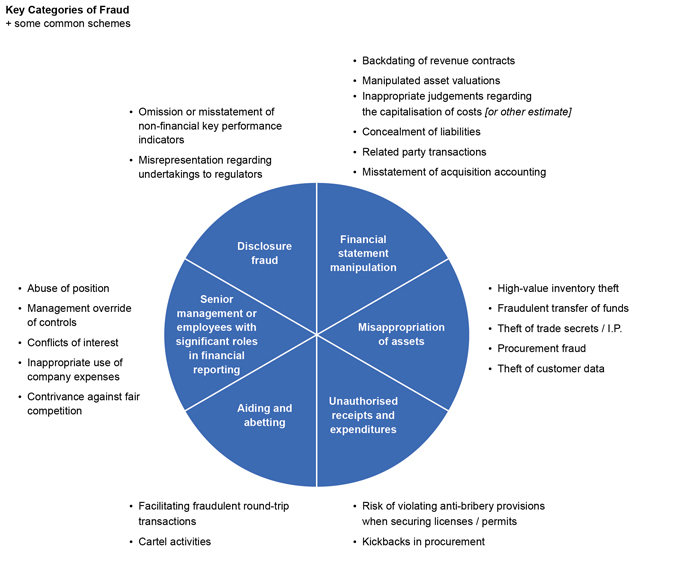

During the process of identification of fraud risks, specific consideration is given to a number of factors, including:

-

Type of risk: fraudulent financial reporting or misappropriation of assets.

-

Significance of risk: whether it is of a magnitude that could result in a material misstatement.

-

Likelihood of the risk: likelihood that it would result in a material misstatement.

-

Pervasiveness of the risk: pervasive to the financial statements as a whole or specifically related to a particular assertion, account, or class of transactions.

Unlike risks due to error, where the assessment of risk depends on the nature of the item, the magnitude of potential misstatements and the likelihood of the misstatements occurring, the nature of fraud risks is different given their pervasiveness. Accordingly, all identified risks due to fraud are assessed as significant.

CAS Guidance

In some cases, all of those charged with governance are involved in managing the entity. This may be the case in a small entity where a single owner manages the entity and no one else has a governance role. In these cases, there is ordinarily no action on the part of the auditor because there is no oversight separate from management (CAS 240.A22).

In the case of a small entity, some or all of these considerations may be inapplicable or less relevant. For example, a smaller entity may not have a written code of conduct but, instead, may have developed a culture that emphasizes the importance of integrity and ethical behavior through oral communication and by management example. Domination of management by a single individual in a small entity does not generally, in and of itself, indicate a failure by management to display and communicate an appropriate attitude regarding internal control and the financial reporting process. In some entities, the need for management authorization can compensate for otherwise deficient controls and reduce the risk of employee fraud. However, domination of management by a single individual can be a potential deficiency in internal control since there is an opportunity for management override of controls (CAS 240.A28).