Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

5034 Components of internal control—The information system and communication

Sep-2022

In This Section

Understanding of the information system

Understanding information processing activities within business processes

Understanding the IT environment relevant to the information system

Identify and document IT dependencies

Understanding a business process including the flow of a transaction through walkthrough

Other Considerations Relevant to Financial Reporting

Understanding of the entity’s communication

Understanding of the information system

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall obtain an understanding of the entity’s information system and communication relevant to the preparation of the financial statements, through performing risk assessment procedures, by (CAS 315.25):

(a) Understanding the entity’s information processing activities, including its data and information, the resources to be used in such activities and the policies that define, for significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures:

(i) How information flows through the entity’s information system, including how:

a. Transactions are initiated, and how information about them is recorded, processed, corrected as necessary, incorporated in the general ledger and reported in the financial statements; and

b. Information about events and conditions, other than transactions, is captured, processed and disclosed in the financial statements;

(ii) The accounting records, specific accounts in the financial statements and other supporting records relating to the flows of information in the information system;

(iii) The financial reporting process used to prepare the entity’s financial statements, including disclosures; and

(iv) The entity’s resources, including the IT environment, relevant to (a)(i) to (a)(iii) above;

CAS Guidance

The controls in the information system and communication, and control activities components are primarily direct controls (i.e., controls that are sufficiently precise to prevent, detect or correct misstatements at the assertion level (CAS 315.A123):

The auditor is required to understand the entity’s information system and communication because understanding the entity’s policies that define the flows of transactions and other aspects of the entity’s information processing activities relevant to the preparation of the financial statements, and evaluating whether the component appropriately supports the preparation of the entity’s financial statements, supports the auditor’s identification and assessment of risks of material misstatement at the assertion level. This understanding and evaluation may also result in the identification of risks of material misstatement at the financial statement level when the results of the auditor’s procedures are inconsistent with expectations about the entity’s system of internal control that may have been set based on information obtained during the engagement acceptance or continuance process (CAS 315.A124).

Included within the entity’s system of internal control are aspects that relate to the entity’s reporting objectives, including its financial reporting objectives, but may also include aspects that relate to its operations or compliance objectives, when such aspects are relevant to financial reporting. Understanding how the entity initiates transactions and captures information as part of the auditor’s understanding of the information system may include information about the entity’s systems (its policies) designed to address compliance and operations objectives because such information is relevant to the preparation of the financial statements. Further, some entities may have information systems that are highly integrated such that controls may be designed in a manner to simultaneously achieve financial reporting, compliance and operational objectives, and combinations thereof (CAS 315.A132).

Understanding the entity’s information system also includes an understanding of the resources to be used in the entity’s information processing activities. Information about the human resources involved that may be relevant to understanding risks to the integrity of the information system include (CAS 315.A133).

The competence of the individuals undertaking the work;

- Whether there are adequate resources; and

- Whether there is appropriate segregation of duties.

The auditor’s understanding of the information system may be obtained in various ways and may include (CAS 315.A136):

Inquiries of relevant personnel about the procedures used to initiate, record, process and report transactions or about the entity’s financial reporting process;

-

Inspection of policy or process manuals or other documentation of the entity’s information system;

-

Observation of the performance of the policies or procedures by entity’s personnel; or

-

Selecting transactions and tracing them through the applicable process in the information system (i.e., performing a walk‑through).

The auditor may also use automated techniques to obtain direct access to, or a digital download from, the databases in the entity’s information system that store accounting records of transactions. By applying automated tools or techniques to this information, the auditor may confirm the understanding obtained about how transactions flow through the information system by tracing journal entries, or other digital records related to a particular transaction, or an entire population of transactions, from initiation in the accounting records through to recording in the general ledger. Analysis of complete or large sets of transactions may also result in the identification of variations from the normal, or expected, processing procedures for these transactions, which may result in the identification of risks of material misstatement (CAS 315.A137).

Financial statements may contain information that is obtained from outside of the general and subsidiary ledgers. Examples of such information that the auditor may consider include (CAS 315.A138):

-

Information obtained from lease agreements disclosed in the financial statements.

-

Information disclosed in the financial statements that is produced by an entity’s risk management system.

-

Fair value information produced by management’s experts and disclosed in the financial statements.

-

Information disclosed in the financial statements that has been obtained from models, or from other calculations used to develop estimates recognized or disclosed in the financial statements, including information relating to the underlying data and assumptions used in those models, such as:

- Assumptions developed internally that may affect an asset’s useful life; or

- Data such as interest rates that are affected by factors outside the control of the entity.

-

Information disclosed in the financial statements about sensitivity analyses derived from financial models that demonstrates that management has considered alternative assumptions.

-

Information recognized or disclosed in the financial statements that has been obtained from an entity’s tax returns and records.

-

Information disclosed in the financial statements that has been obtained from analyses prepared to support management’s assessment of the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern, such as disclosures, if any, related to events or conditions that have been identified that may cast significant doubt on the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern.

Certain amounts or disclosures in the entity’s financial statements (such as disclosures about credit risk, liquidity risk, and market risk) may be based on information obtained from the entity’s risk management system. However, the auditor is not required to understand all aspects of the risk management system, and uses professional judgment in determining the necessary understanding (CAS 315.A139).

The information system relevant to the preparation of the financial statements consists of activities and policies, and accounting and supporting records, designed and established to (CAS 315.Appendix 3.15):

-

Initiate, record, process, and report entity transactions (as well as to capture, process and disclose information about events and conditions other than transactions) and to maintain accountability for the related assets, liabilities, and equity.

-

Resolve incorrect processing of transactions, for example, automated suspense files and procedures followed to clear suspense items out on a timely basis.

-

Process and account for system overrides or bypasses to controls.

-

Incorporate information from transaction processing in the general ledger (e.g., transferring of accumulated transactions from a subsidiary ledger).

-

Capture and process information relevant to financial reporting for events and conditions other than transactions, such as the depreciation and amortization of assets and changes in the recoverability of assets.

-

Ensure information required to be disclosed by the applicable financial reporting framework is accumulated, recorded, processed, summarized and appropriately reported in the financial statements.

An entity’s business processes include the activities designed to (CAS 315.Appendix 3.16):

- Develop, purchase, produce, sell and distribute an entity’s products and services.

- Ensure compliance with laws and regulations.

- Record information, including accounting and financial reporting information.

Business processes result in the transactions that are recorded, processed and reported by the information system.

OAG Guidance

Understanding the entity’s information system involves determining how financial information that is relevant to the preparation of the financial statements is initiated, recorded, processed, corrected, and incorporated in the general ledger and reported in the financial statements. This understanding includes gaining knowledge of the IT environment relevant to the flow of transactions and processing of information in the entity’s information system (i.e., IT applications and supporting IT infrastructure) that enable the company to present their financial statements. Gaining this understanding is not performed through a stand‑alone process, but rather consists of the aggregation of information accumulated through the understanding of the underlying business processes. We consider a business process to be significant if it relates to significant FSLIs as described in OAG Audit 5042. The understanding of the underlying business processes includes considering how financial information related to transactions is captured, processed and reported within the entity’s information systems, as well as the accounting estimates incorporated and the journal entries recorded as a result of the business process resulting in the amounts ultimately reflected in the financial statements. Our detailed understanding may be embedded in our understanding of the respective business processes; however, our overall understanding of the information system and communication component typically summarizes the linkage between the activities performed within the significant business processes, the IT applications and supporting IT infrastructure, and the information presented in the financial statements.

See the block below Understanding information processing activities within business processes for further discussion regarding obtaining an understanding of business processes including the end‑to‑end flow of transactions and controls.

Understanding the entity’s information system and communication component of the entity’s system of internal controls includes considering:

-

Business processes that are considered to be significant to financial reporting, including:

-

How the entity’s significant classes of transactions, account balances, and disclosures (FSLIs) (and management information, if relevant) are mapped to business processes, (including the financial reporting process itself) and IT applications for each significant management unit.

-

What significant sub‑processes underlie each significant business process, including the financial reporting process.

-

How the use of management information impacts financial reporting (e.g., when management manages operating results separately for each individual line of business we might identify more than one business process or sub‑processes for a single FSLI).

-

-

The entity’s information system, including:

-

How policies and procedures relating to the entity’s use of IT resources (including applications or other aspects of the IT environment) relevant to the flow of transactions and processing of information impact the audit, including the impact of changes in the IT environment.

-

When performing procedures to obtain our understanding of the entity’s information processing activities, we identify and obtain an understanding of controls that management has implemented to capture, process and report events and transactions (i.e., as controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements). The understanding of the information processing activities and identified controls forms a basis for identifying and assessing risks of material misstatement at the assertion level as well as controls that address those risks (controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level in the control activities component). CAS 315.26(a) requires that we evaluate the design and implementation of controls in the control activities component as it assists us in understanding management’s approach to addressing risks and provides a basis for designing and performing further audit procedures. We document the understanding of the information processing activities and identified controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements as part of the information system and communication component even if we decide not to evaluate their design effectiveness and implementation.

Related guidance

The block Complexity of IT environment provides further guidance on considerations regarding the complexity of the entity’s IT environment.

OAG Audit 5035.1 contains guidance on the identification of controls within the control activities

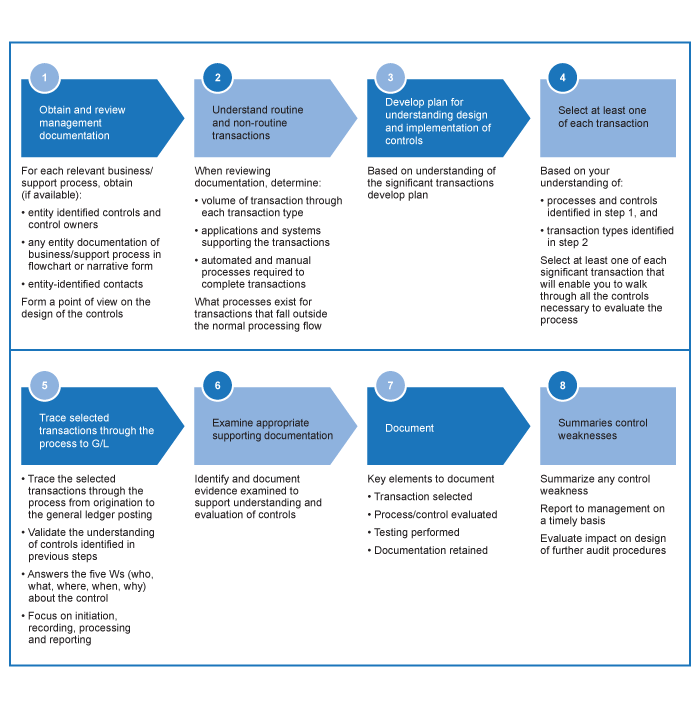

Understanding information processing activities within business processes

CAS Guidance

As explained in paragraph A49, the auditor’s understanding of the entity and its environment, and the applicable financial reporting framework, may assist the auditor in developing initial expectations about the classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures that may be significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures. In obtaining an understanding of the information system and communication component in accordance with paragraph 25(a), the auditor may use these initial expectations for the purpose of determining the extent of understanding of the entity’s information processing activities to be obtained (CAS 315.A126).

The auditor’s understanding of the information system includes understanding the policies that define flows of information relating to the entity’s significant classes of transactions, account balances, and disclosures, and other related aspects of the entity’s information processing activities. This information, and the information obtained from the auditor’s evaluation of the information system may confirm or further influence the auditor’s expectations about the significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures initially identified (CAS 315.A127).

The auditor’s identification and assessment of risks of material misstatement at the assertion level is influenced by both the auditor’s (CAS 315.A130):

-

Understanding of the entity’s policies for its information processing activities in the information system and communication component, and

-

Identification and evaluation of controls in the control activities component.

Matters the auditor may consider when understanding the policies that define the flows of information relating to the entity’s significant classes of transactions, account balances, and disclosures in the information system and communication component include the nature of (CAS 315.A134):

-

The data or information relating to transactions, other events and conditions to be processed;

-

The information processing to maintain the integrity of that data or information; and

-

The information processes, personnel and other resources used in the information processing process.

Obtaining an understanding of the entity’s business processes, which include how transactions are originated, assists the auditor obtain an understanding of the entity’s information system relevant to financial reporting in a manner that is appropriate to the entity’s circumstances (CAS 315.A135).

OAG Guidance

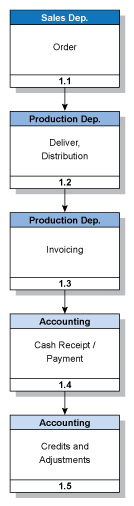

Business processes comprise multiple sub‑processes for which specific accounting procedures and controls are established by an entity’s management. For example, process sales orders, maintain customer data, maintain pricing, process invoices, process returns, and apply cash may be distinct sub‑processes making up the revenue and receivables process. Each sub‑process may be further divided by specific type of transaction, for example, process sales orders may be subdivided into cash sales and credit sales, or into foreign sales and domestic sales. In each of the business processes, transactions are initiated, recorded, processed, corrected (if necessary) and reported in the financial statements. Business processes can also include events and conditions other than transactions that are captured, processed and disclosed in the financial statements (e.g., restrictions on the use of some assets such as cash).

See OAG Audit 5012.3 for guidance on developing an initial expectation about the classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures that may be significant FSLIs, identifying related business processes and how these business processes link to FSLIs. CAS 315.25(a) requires us to obtain an understanding of the business processes for each significant FSLI. Furthermore, as described in OAG Audit 5012.3, when a business process relates to a material FSLI, even if we believe we may not identify any risks of material misstatement for that FSLI at the assertion level, we would perform procedures to understand and evaluate the entity’s information system(s) relevant to this business process. This is because we generally need an understanding of the business process underlying the material FSLI in order to consider whether there are any risks of material misstatement related to the FSLI at the assertion level. Therefore, the extent of this understanding needs to be sufficient to provide a basis for concluding whether there are any identified risks of material misstatement within the business process, but, in some cases, the level of our understanding may not need to be as extensive as for significant business processes. For example, our understanding of the information systems related to these FSLIs may be obtained predominantly from inquiries of relevant personnel about the procedures used to initiate, record, process and report transactions, supported by corroborating procedures such as inspection or observation, which would not necessarily require a walkthrough of transactions through the entire business process. Furthermore, it would be unlikely that we would identify controls within such a business process as representing controls in the controls activities component given our conclusion that no risks of material misstatement have been identified.

The nature and extent of the procedures we perform to obtain an understanding of business processes will vary depending on the complexity of the business processes itself. When obtaining an understanding we also determine whether the business processes are transactional or periodic based on the following characteristics:

-

Transactional business processes: Such business processes are generally fundamental to the way in which an entity generates revenues and incurs expenses and may extensively use information technology. These business processes address the initiation, recording, processing, and reporting of higher numbers and various types of routine transactions throughout the reporting period. We expect a greater number of controls within the control activities component that we need to understand in transactional business processes than in periodic business processes. Such controls also operate throughout the period and as of the reporting date. Examples of transactional business processes often include but are not limited to: revenue and receivables; purchasing and payables; production and inventory; and payroll.

-

Periodic business processes: Such processes address the initiation, recording, processing, and reporting of lower numbers of transactions, including significant one‑time or infrequent periodic transactions. We expect fewer controls within control activities that we need to understand for periodic business processes than for transactional business processes. These controls generally operate periodically or as of the reporting date, such as authorizations and reviews of account reconciliations, or the review of accounts subject to judgment and estimation. Examples of these business processes often include, but are not limited to: capital and equity, financing, intangible assets and goodwill, property plant and equipment, share‑based compensation awards, taxes, and treasury.

A business process may be considered transactional to one entity while the same business process may be considered periodic to another. For example, a highly complex tax business process operating in multiple tax jurisdictions and with rapidly changing regulations that is supported by many controls and information systems and applications, may represent a transactional business process, while a simple taxes business process that is manual in nature and operating only at the end of the fiscal year may represent a periodic business process.

The work effort needed to obtain an understanding of the business process depends on whether the process is periodic or transactional and also on the complexity of the process. Some examples of characteristics that would have an impact on the nature and extent of the procedures we perform when obtaining an understanding also include:

-

Complexity of the transactions

-

Complexity of IT environment (e.g., number of IT applications and dependencies)

-

Number of events and conditions that impact changes in the business processes

-

Complexity of financial reporting

-

Number of non‑standard journal entries

-

Initial expectation of risks identified within the business processes for the purpose of determining the extent of understanding of the entity’s information processing activities to be obtained

Example:

|

Business process characteristics |

Nature and extent of procedures for example business process |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Inquiries of personnel and inspection of documentation |

Inspection of documentation, observation of performance of the procedures, or walkthroughs |

|

|

Intangible Assets and Goodwill |

Revenue and Receivables |

|

|

Complexity of the transactions |

Simple non‑complex transactions during the period (purchases of intangible items, amortization, disposals) |

High complexity due to GAAP requirements such as IFRS 15 (5 step revenue recognition model) |

|

Number of IT dependencies |

Limited number of IT dependencies (e.g., summary reports and automated amortization calculation) |

High number of IT dependencies used to measure and recognize revenue and calculate expected credit losses (ECL) for accounts receivable and contract assets (e.g., interfaces, automated calculation of ECL, periodic reports used in the execution of management’s control) |

|

Number of events and conditions that impact changes in the business processes |

Limited number of events. Goodwill transaction occurring rarely. Factors impacting impairment testing considered at period end only because no interim external compliance or financial reporting required. |

Many external factors impacting transactions throughout the period such as the macroeconomic environment impacting the model used and calculations of ECL for accounts receivable. |

| Complexity of financial reporting | The complexity of financial reporting is mainly in the area of annual impairment testing. Identified accounting estimates relate to useful lives of the intangible assets and estimation of the recoverable amount of goodwill. | Higher complexity due to detailed GAAP requirements for individual transactions (e.g., revenue recognition under IFRS 15) as well as additional asset recoverability considerations (e.g., IFRS 9). This may lead to multiple accounting estimates identified in the business process. |

| Number of non‑standard journal entries | Limited | Depends on the complexity and nature of individual revenue transactions, but non‑standard journals are not uncommon. |

| Initial expectation of risks identified within the business processes for the purpose of determining the extent of understanding of the entity’s information processing activities to be obtained. | Based on the entity circumstances (i.e., consistently high operating profits and cash flows and no history of impairments) normal level of risk of material misstatement related to valuation with no fraud risks identified. | Rebuttable presumption of significant risk of fraud in revenue recognition. Additional elevated or significant risks of material misstatement at the assertion level. |

When obtaining an understanding of the business procedures relevant to the entity’s financial reporting we determine what controls management put in place to capture, process and report events and transactions. We further determine which of the controls we consider to be within the control activities component subject to design effectiveness and implementation evaluation and whether we plan to test them for operating effectiveness. Points to consider when identifying these business processes include:

-

How the use of management information impacts financial reporting.

-

How, for each significant management unit, the FSLIs are mapped to business processes, (including the financial reporting process itself), IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment.

-

What significant sub‑processes underlie each business process, including the financial reporting process.

See OAG Audit 5035.1 for further guidance on identifying relevant business processes and how business processes link to FSLIs within the audit file.

Use of entity‑prepared documentation vs. documentation prepared by OAG

Where we conclude that the entity’s documentation of business processes, transaction flows and controls is sufficient for our purposes, using this documentation may be an effective method for documenting our understanding of business processes and the entity’s controls.

For the entity prepared documentation to be sufficient for our purposes, it would:

-

Describe how transactions are initiated, recorded, processed, and reported

-

Allow us to understand business processes and transaction flows necessary to identify controls to be included in control activities, including controls related to significant risks, and controls for which we plan to test operating effectiveness

-

Be at an appropriate level of detail, including enough information about the flow of transactions to identify points at which material misstatements due to fraud or error might be likely to occur;

-

Identify and describe controls that we believe are important to obtain a sufficient understanding of the end‑to‑end business process

-

Be prepared in a form or summarized, to the extent necessary, for inclusion in our workpapers, so that we can document our understanding of the end‑to‑end business process.

Understanding the financial reporting process used to prepare the entity’s financial statements

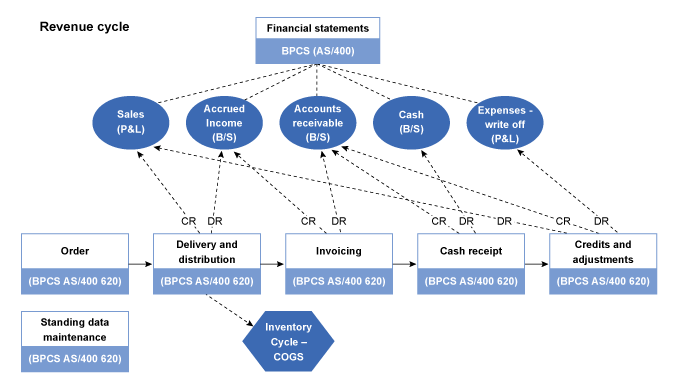

We need to gain an understanding of how the financial statements are generated, which includes mapping the linkage of the financial information from the significant business processes and IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment, that initiate, record and process the information to the financial statements. We also need to take into account any other sources of information from outside of the general ledger and subsidiary ledgers. CAS 315.A138 contains examples of such information sources that could be included in the entity’s financial statements.

We may use management’s mapping documentation (if available) or prepare our own, such as the one illustrated in the diagram below.

Our understanding of the entity’s information system(s) considers the following:

-

What information systems/applications underlie the initiation, authorization, recording, processing, correcting (as necessary), transferring to general ledger, and reporting of transactions in FSLIs?

-

How are the business processes and information system implemented throughout the entity (e.g., by function, geography, management unit)?

-

What are the significant processes and FSLIs and how do they relate to financial statement line items?

-

What is the source of the information reported to these financial statement area line items?

-

How do the significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures and related financial statement line items link to business processes?

-

Are the significant business processes centralized or managed separately by management units within the entity?

-

What transactions occur within the significant business processes?

-

How are these transactions initiated? Are they initiated electronically?

-

What are the systems and technologies that support the activities within those significant business processes? (see further guidance in the block Complexity of IT environment)

-

How are the information systems structured?

-

Who is responsible for reviewing and approving the systems used by the entity?

-

What is the basis upon which management considers the information to be reliable (i.e., complete and accurate?

-

How do the transactions in the underlying systems flow into the entity’s general ledger system? Manual or electronic interfaces?

-

How does management know that management information is reflected in the trial balance and ultimately the financial statements?

-

Are any adjustments made between the underlying information and the financial statements? Why? How are they monitored?

-

What information in the financial statements is not accumulated or captured in the general ledger (e.g., detailed disclosure information)? How does the entity identify and prepare this information?

-

What IT dependencies (e.g. automated controls, reports, calculations, security, and interfaces) are important to evaluating the design of controls and determining further audit procedures?

In addition to the financial information that is directly reflected in the financial statements, management may use other information for operating and controlling business or financial reporting activities. Similar to financial information, when this other information is relevant to the audit, we apply the considerations above to document our understanding of how this other information is generated, the related information systems, and how we obtain audit evidence over the completeness and accuracy of the information.

Understanding the IT environment relevant to the information system

CAS Guidance

The auditor’s understanding of the information system includes the IT environment relevant to the flows of transactions and processing of information in the entity’s information system because the entity’s use of IT applications or other aspects in the IT environment may give rise to risks arising from the use of IT (CAS 315.A140).

The understanding of the entity’s business model and how it integrates the use of IT may also provide useful context to the nature and extent of IT expected in the information system (CAS 315.A141).

The auditor’s understanding of the IT environment may focus on identifying, and understanding the nature and number of, the specific IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment that are relevant to the flows of transactions and processing of information in the information system. Changes in the flow of transactions, or information within the information system may result from program changes to IT applications, or direct changes to data in databases involved in processing, or storing those transactions or information (CAS 315.A142).

The auditor may identify the IT applications and supporting IT infrastructure concurrently with the auditor’s understanding of how information relating to significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures flows into, through and out the entity’s information system (CAS 315.A143).

An entity’s system of internal control contains manual elements and automated elements (i.e., manual and automated controls and other resources used in the entity’s system of internal control). An entity’s mix of manual and automated elements varies with the nature and complexity of the entity’s use of IT. An entity’s use of IT affects the manner in which the information relevant to the preparation of the financial statements in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework is processed, stored and communicated, and therefore affects the manner in which the entity’s system of internal control is designed and implemented. Each component of the entity’s system of internal control may use some extent of IT (CAS 315.Appendix 5.1).

Generally, IT benefits an entity’s system of internal control by enabling an entity to:

-

Consistently apply predefined business rules and perform complex calculations in processing large volumes of transactions or data;

-

Enhance the timeliness, availability and accuracy of information;

-

Facilitate the additional analysis of information;

-

Enhance the ability to monitor the performance of the entity’s activities and its policies and procedures;

-

Reduce the risk that controls will be circumvented; and

-

Enhance the ability to achieve effective segregation of duties by implementing security controls in IT applications, databases and operating systems.

The characteristics of manual or automated elements are relevant to the auditor’s identification and assessment of the risks of material misstatement, and further audit procedures based thereon. Automated controls may be more reliable than manual controls because they cannot be as easily bypassed, ignored, or overridden, and they are also less prone to simple errors and mistakes. Automated controls may be more effective than manual controls in the following circumstances (CAS 315. Appendix 5.2):

-

High volume of recurring transactions, or in situations where errors that can be anticipated or predicted can be prevented, or detected and corrected, through automation.

-

Controls where the specific ways to perform the control can be adequately designed and automated.

The entity’s information system may include the use of manual and automated elements, which also affect the manner in which transactions are initiated, recorded, processed, and reported. In particular, procedures to initiate, record, process and report transactions may be enforced through the IT applications used by the entity, and how the entity has configured those applications. In addition, records in the form of digital information may replace or supplement records in the form of paper documents (CAS 315. Appendix 5.3).

Entities may use emerging technologies (e.g., blockchain, robotics or artificial intelligence) because such technologies may present specific opportunities to increase operational efficiencies or enhance financial reporting. When emerging technologies are used in the entity’s information system relevant to the preparation of the financial statements, the auditor may include such technologies in the identification of IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment that are subject to risks arising from the use of IT. While emerging technologies may be seen to be more sophisticated or more complex compared to existing technologies, the auditor’s responsibilities in relation to IT applications and identified general IT controls in accordance with paragraph 26(b)‒(c) remain unchanged (CAS 315. Appendix 5.5).

OAG Guidance

In understanding the IT environment and the IT resources used in information processing activities, we consider the information obtained in our understanding of the entity’s business model and how it integrates the use of IT because this understanding helps us form an expectation as to the entity’s level of IT resources (see OAG Audit 5023). To achieve this, we obtain an understanding of IT resources relevant to the flows of transactions and processing of information in the information system, which includes:

- IT applications

- IT infrastructure

- IT processes and personnel involved in those processes

Our understanding of information generated by the entity’s information system is obtained through discussions with management responsible for both business processes and the information systems. We exercise judgment with input from senior members of the engagement team and IT Audit (where involved) to determine the extent of understanding of the entity’s information systems to be obtained and documented, including the format of the documentation (e.g., narrative commentary, flowcharts). The extent of understanding will depend on the extent of the use of IT in the entity’s business model and activities relevant to the significant FSLIs.

The entity may use a range of IT resources across their operations, but our identification and understanding are focused on how information relating to significant FSLIs flows into, through and out of the entity’s information system. For example, if the entity uses a report generated from an IT application in the operation of a control over inventory under custody of a third party that is not expected to be a significant FSLI, the engagement team may conclude that this IT resource (report of inventory in custody of third party) is not relevant to our understanding.

The evolving technology environment can increase the complexity of an entity’s IT environment and may include management making use of emerging technologies. When the entity uses emerging technologies as part of their financial reporting process we need to understand the technologies and the role they play in the entity’s information processing or other financial reporting activities and consider whether there are risks arising from their use. Given the potential complexities of these technologies, there is an increased likelihood that the engagement team may decide to engage specialists and/or auditor’s experts to help understand whether and how their use impacts the entity’s financial reporting processes and may give rise to risks from the use of IT. Some examples of emerging technologies are:

- Blockchain, including cryptocurrency businesses (e.g., token issuers, custodial services, exchanges, miners, investors)

- Robotics

- Artificial Intelligence

- Internet of Things

- Biometrics

- Drones

Depending on the complexity of the IT environment the involvement of IT Audit may be appropriate or required by policy. Refer to the policy for involvement of IT Audit in OAG Audit 3102 and refer to the block Complexity of IT environment for guidance on assessing the complexity of an entity’s IT environment.

Identify and document IT dependencies

OAG Guidance

As part of our procedures to understand the entity’s information system we identify the IT dependencies relevant to the entity’s flow of transactions and processing of financial information.

Why is this important?

Identifying and documenting the entity’s IT dependencies in a consistent, clear manner helps to identify the entity’s reliance upon IT, understand how IT is integrated into the entity’s business model, identify potential risks arising from the use of IT, identify related ITGCs, and enables us to develop an effective and efficient audit approach.

How IT dependencies arise

IT Dependencies are created when IT is used to initiate, authorize, record, process, or report transactions or other financial data for inclusion in financial statements. They include information processing controls and other control procedures related to the corresponding assertions for significant FSLIs or that may be critical to the effective functioning of manual controls that depend on the use of IT.

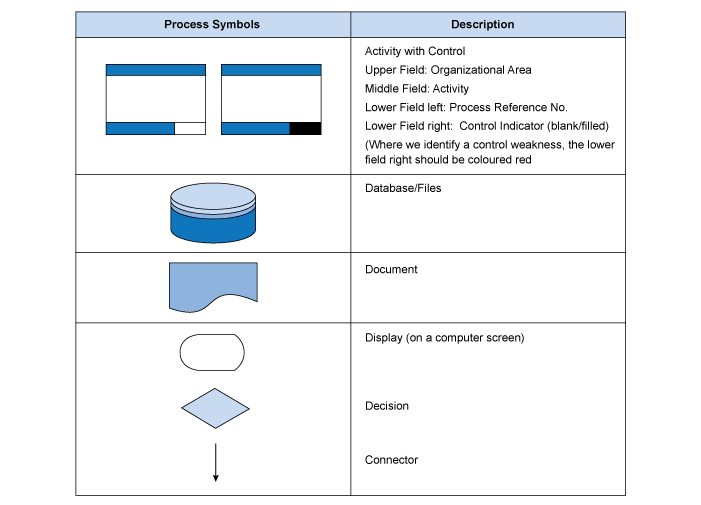

There are five types of IT dependencies as described below:

Type |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Automated Controls |

Automated controls are designed into the IT environment to enforce business rules. For example, many IT applications include format checks (e.g., only a particular date format is accepted), existence checks (e.g., customer number exists on customer masterfile), and/or reasonableness checks (e.g., maximum payment amount) when a transaction is entered. |

|

Reports |

System generated reports are information generated by IT systems. These reports are often used in an entity’s execution of a manual control, including business performance reviews, or may be the source of entity information used by us when selecting items for testing, performing substantive tests of details or performing a substantive analytical procedure. |

|

Calculations |

Calculations are accounting procedures that are performed by an IT system instead of a person. For example, the system will apply the ’straight‑line’ depreciation formula to calculate depreciation of an asset (i.e., cost of the asset, less the residual value of the asset at the end of its useful life divided by the useful life of the asset) or the system will calculate the value of the amount invoiced to a customer by multiplying the item price times the quantity shipped. |

|

Security |

Security including segregation of duties is enabled by the IT environment to restrict access to information and to determine the separation of roles and responsibilities that could allow an employee to perpetrate and conceal errors or fraud, or to process errors that go undetected. |

|

Interfaces |

Interfaces are programmed logic that transfer data from one IT system to another. For example, an interface may be programmed to transfer data from a payroll sub‑ledger to the general ledger. |

Understanding and responding to risks arising from IT dependencies

When we identify IT dependencies that are relevant to the entity’s flow of transactions and processing of financial information, we need to understand how management responds to the associated risks that may arise from them. Management may implement information technology general controls (ITGCs) to address risks related to IT dependencies. ITGCs support the continued proper operation of the IT environment, including the continued effective functioning of information processing controls and the integrity of information in the entity’s information system.

IT dependencies may also affect the design of the entity’s controls and how they are implemented. Therefore, we consider IT dependencies relevant to our audit and evaluate the related risks arising from the use of IT for the purpose of assessing the risk of material misstatement and to determine the most effective and efficient approach to testing ITGCs or performing other audit procedures to address risks arising from IT dependencies. Even if our audit plan does not include testing the operating effectiveness of ITGCs, the risks which these controls are designed to address will need to be understood as part of our risk assessment. See OAG Audit 5035.2 for further information on identification of risks arising from the use of IT and the related ITGC considerations

Updating our understanding of IT dependencies

While performing our audit procedures we may identify additional IT dependencies that were not previously identified. For example, as part of controls testing we may identify a system‑generated report used in the execution of a manual control that we did not identify when evaluating the design and implementation of the control during the understanding phase of the audit. For such IT dependencies we update our documented understanding to include the IT dependency, and we plan and execute the procedures to test it.

Complexity of IT environment

CAS Guidance

In obtaining an understanding of the IT environment relevant to the flows of transactions and information processing in the information system, the auditor gathers information about the nature and characteristics of the IT applications used, as well as the supporting IT infrastructure and IT. The following table includes examples of matters that the auditor may consider in obtaining the understanding of the IT environment and includes examples of typical characteristics of IT environments based on the complexity of IT applications used in the entity’s information system. However, such characteristics are directional and may differ depending on the nature of the specific IT applications in use by an entity (CAS 315. Appendix 5.4).

|

Examples of typical characteristics of: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-complex commercial software |

Mid‑size and moderately complex commercial software or IT applications |

Large or complex IT applications (e.g., ERP systems) |

|

|

Matters related to extent of automation and use of data: |

|||

| The extent of automated procedures for processing, and the complexity of those procedures, including, whether there is highly automated, paperless processing. | N/A |

N/A |

Extensive and often complex automated procedures |

| The extent of the entity’s reliance on system‑generated reports in the processing of information. | Simple automated report logic |

Simple relevant automated report logic |

Complex automated report logic; Report‑writer software |

| How data is input (i.e., manual input, customer or vendor input, or file load). | Manual data inputs |

Small number of data inputs or simple interfaces |

Large number of data inputs or complex interfaces |

| How IT facilitates communication between applications, databases or other aspects of the IT environment, internally and externally, as appropriate, through system interfaces. | No automated interfaces (manual inputs only) |

Small number of data inputs or simple interfaces |

Large number of data inputs or complex interfaces |

| The volume and complexity of data in digital form being processed by the information system, including whether accounting records or other information are stored in digital form and the location of stored data. | Low volume of data or simple data that is able to be verified manually; Data available locally |

Low volume of data or simple data |

Large volume of data or complex data; Data warehouses; Use of internal or external IT service providers (e.g., third‑party storage or hosting of data) |

|

Matters related to the IT applications and IT infrastructure: |

|||

| The type of application (e.g., a commercial application with little or no customization, or a highly‑customized or highly‑integrated application that may have been purchased and customized or developed in‑house). | Purchased application with little or no customization | Purchased application or simple legacy or low‑end ERP applications with little or no customization | Custom developed applications or more complex ERPs with significant customization |

| The complexity of the nature of the IT applications and the underlying IT infrastructure. | Small, simple laptop or client server‑based solution | Mature and stable mainframe, small or simple client server, software as a service cloud | Complex mainframe, large or complex client server, web‑facing, infrastructure as a service cloud |

| Whether there is third‑party hosting or outsourcing of IT. | If outsourced, competent, mature, proven provider (e.g., cloud provider) | If outsourced, competent, mature, proven provider (e.g., cloud provider) | Competent, mature proven provider for certain applications and new or start‑up provider for others |

| Whether the entity is using emerging technologies that affect its financial reporting. |

No use of emerging technologies | Limited use of emerging technologies in some applications | Mixed use of emerging technologies across platforms |

|

Matters related to IT processes: |

|||

|

The personnel involved in maintaining the IT environment (the number and skill level of the IT support resources that manage security and changes to the IT environment). |

Few personnel with limited IT knowledge to process vendor upgrades and manage access | Limited personnel with IT skills/dedicated to IT | Dedicated IT departments with skilled personnel, including programming skills |

| The complexity of processes to manage access rights. | Single individual with administrative access manages access rights | Few individuals with administrative access manage access rights |

Complex processes managed by IT department for access rights |

| The complexity of the security over the IT environment, including vulnerability of the IT applications, databases, and other aspects of the IT environment to cyber risks, particularly when there are web‑based transactions or transactions involving external interfaces. | Simple on‑premise access with no external web‑facing elements |

Some web‑based applications with primarily simple, role‑based security |

Multiple platforms with web‑based access and complex security models |

| Whether program changes have been made to the manner in which information is processed, and the extent of such changes during the period. | Commercial software with no source code installed |

Some commercial applications with no source code and other mature applications with a small number or simple changes; traditional systems development lifecycle |

New or large number or complex changes, several development cycles each year |

| Whether there was a major data conversion during the period and, if so, the nature and significance of the changes made, and how the conversion was undertaken. | Changes limited to version upgrades of commercial software | Changes consist of commercial software upgrades, ERP version upgrades, or legacy enhancements | New or large number or complex changes, several development cycles each year, heavy ERP customization |

| Whether there was a major data conversion during the period and, if so, the nature and significance of the changes made, and how the conversion was undertaken. | Software upgrades provided by vendor; No data conversion features for upgrade | Minor version upgrades for commercial software applications with limited data being converted | Major version upgrade, new release, platform change |

Obtaining an understanding of the entity’s IT environment may be more easily accomplished for a less complex entity that uses commercial software and when the entity does not have access to the source code to make any program changes. Such entities may not have dedicated IT resources but may have a person assigned in an administrator role for the purpose of granting employee access or installing vendor‑provided updates to the IT applications. Specific matters that the auditor may consider in understanding the nature of a commercial accounting software package, which may be the single IT application used by a less complex entity in its information system, may include (CAS 315.Appendix 5.6):

-

The extent to which the software is well established and has a reputation for reliability;

-

The extent to which it is possible for the entity to modify the source code of the software to include additional modules (i.e., add‑ons) to the base software, or to make direct changes to data;

-

The nature and extent of modifications that have been made to the software. Although an entity may not be able to modify the source code of the software, many software packages allow for configuration (e.g., setting or amending reporting parameters). These do not usually involve modifications to source code; however, the auditor may consider the extent to which the entity is able to configure the software when considering the completeness and accuracy of information produced by the software that is used as audit evidence; and

-

The extent to which data related to the preparation of the financial statements can be directly accessed (i.e., direct access to the database without using the IT application) and the volume of data that is processed. The greater the volume of data, the more likely the entity may need controls that address maintaining the integrity of the data, which may include general IT controls over unauthorized access and changes to the data.

Complex IT environments may include highly‑customized or highly‑integrated IT applications and may therefore require more effort to understand. Financial reporting processes or IT applications may be integrated with other IT applications. Such integration may involve IT applications that are used in the entity’s business operations and that provide information to the IT applications relevant to the flows of transactions and information processing in the entity’s information system. In such circumstances, certain IT applications used in the entity’s business operations may also be relevant to the preparation of the financial statements. Complex IT environments also may require dedicated IT departments that have structured IT processes supported by personnel that have software development and IT environment maintenance skills. In other cases, an entity may use internal or external service providers to manage certain aspects of, or IT processes within, its IT environment (e.g., third‑party hosting) (CAS 315. Appendix 5.7).

OAG Guidance

Why is this important?

Understanding the ways in which the entity relies upon IT and how the IT environment is set up to support the business allows us to better understand where risks might arise from the entity’s use of IT. Understanding how IT is used by the entity is useful when identifying controls over the entity’s IT processes that respond to these risks and support the continued proper operation of the IT environment, including the continued effective functioning of information processing controls and protection of the integrity of the information.

Assessing the complexity of the IT environment also helps us consider whether to involve IT specialists (e.g., IT Audit) in the planning and/or execution of the audit, including initial consideration of whether to include specialists in the complexity assessment.

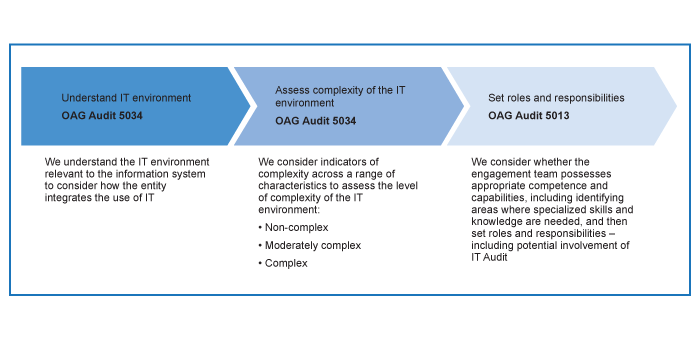

One important reason for understanding the entity’s IT environment, as discussed in the block Understanding the IT environment relevant to the information system, is to assess the complexity of the IT environment relevant to the entity’s information system. Understanding the level of complexity of the IT environment helps us to identify the level of specialized skill needed for the engagement. It also informs our judgments about the expected level of effort needed to identify the risks arising from the entity’s use of IT and the related controls the entity has implemented to address these risks. When the entity is using a combination of IT resources (i.e., IT applications, IT infrastructure, IT processes and personnel) and other characteristics of the IT environment reflect a higher degree of complexity, the core audit team may not have the skills necessary to identify and understand the risks arising from the entity’s use of IT, the related ITGCs and/or assess how these characteristics may impact the risk of material misstatement at the financial statement or assertion level. In this case, we consider involving IT Audit in our complexity assessment and risk assessment procedures.

OAG Audit 3102 includes OAG Policy on the involvement of IT Audit.

Whether we conclude that IT environment is non‑complex, moderately complex or complex we consider involving IT audit personnel in this initial assessment. For further guidance on the involvement of IT Audit, refer to OAG Audit 5013 and OAG Audit 3102.

The flowchart below shows a high‑level overview of the linkage between understanding the IT environment, considering the complexity of the IT environment and setting roles and responsibilities for the engagement:

We assess the complexity of the IT environment and/or certain aspects of the environment, using three levels of complexity: Non‑Complex; Moderately Complex; and Complex. Assessing the level of complexity of the IT environment is a matter of judgment, after considering a combination of entity characteristics.

The presence of one complex characteristic may not necessarily cause us to conclude that the entity has a complex IT environment. Nor would the presence of one non‑complex characteristic necessarily cause us to conclude that the entity has a non‑complex IT environment. Even when we conclude that the entity’s IT environment is complex (or moderately complex), it is still possible that we might conclude that some aspects of the IT environment (e.g., applications, infrastructure or IT processes) have a different level of complexity. For example, if the entity has an IT environment that we conclude is complex we might still conclude that certain applications used by the entity are non‑complex. For these non‑complex applications, we might conclude that the core audit team has sufficient skill to perform some or all of the risk assessment, designing the audit plan and performing further audit procedures. While we may conclude that we will involve IT Audit in the audit work for the other complex aspects of the IT environment.

The table below describes illustrative indicators for each of the three levels of complexity. These are expected to be considered by engagement teams when understanding and performing their assessment of the entity’s IT environment. The indicators are set out using the following characteristics:

- Automation

- Entity’s reliance on system‑generated reports

- Customization

- Business model

- Change

- Use of emerging technologies

CAS 315 provides illustrative examples of characteristics related to IT applications, which can be used to assess the complexity of the IT environment. The complexity of an entity’s IT environment includes consideration of how the entity integrates the use of IT into its business model which may directly impact our assessment of risks of material misstatement. For example, when we identify deficiencies in the entity’s segregation of duties related to restricted access to a specific IT application, this could also impact the effectiveness of segregation of duties related to access controls for other aspects of the IT environment such as the entity’s network infrastructure or operating systems, and it may therefore indicate a higher level of risk of material misstatement at the financial statement level if the impact could be pervasive.

The following table includes characteristics of an IT environment that the engagement team typically considers when obtaining an understanding of the entity’s IT environment. The table also includes examples of indicators of the level of complexity of IT applications used in the entity’s information system. This is not intended as an exhaustive list of indicators, nor is any indicator necessarily determinative of the level of complexity. Examples of individual indicators may not differ significantly between non‑complex and moderately complex but when considered in combination with other relevant indicators provide the basis for overall differentiation of the complexity level. Relevant indicators of complexity may vary depending on the nature of the specific IT applications in use by an entity and how they are integrated into the entity’s business:

|

Automation—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

|

Entity’s reliance on system‑generated reports (see OAG Audit 4028.4 for definitions of report types referenced in some of the indicators below)—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

| Customization—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

|

Business model—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

|

Change—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

|

Use of emerging technologies—Illustrative indicators for each level of complexity |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Non‑complex |

Moderately complex |

Complex |

|

|

|

In a complex IT environment not all aspects of the IT environment are necessarily complex. For example, we may have application(s) assessed as non‑complex commercial software (“off‑the‑shelf” application(s)). When determining our IT strategy and the level of IT Audit involvement across various aspects of the IT environment, we assess the level of complexity at an application level. We may use the examples in the tables above to guide this assessment and the examples provided in CAS 315. Appendix 5 to help assess the level of complexity. The engagement leader may determine, in conjunction with the engagement of IT Audit, that it is appropriate for the core audit team to perform the relevant audit procedures for some applications or other aspects of the IT environment. The level of IT Audit involvement and the testing approach (substantive or controls) can vary across different aspects of the IT environment. However, it may still be beneficial to use specialists as it can be more efficient and effective, for example if processes and controls are homogeneous between non‑complex and complex applications.

Assessing the complexity of IT Environments—Illustrative Examples

The following are examples of various scenarios that illustrate the evaluation of the complexity of different IT environments. The examples are provided for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to illustrate all relevant factors and are not meant as illustrative documentation, because they will vary based on the facts and circumstances of each engagement. The engagement team’s complexity assessment column in the examples below is used by the engagement team to indicate the judgment and rationale applied during the assessment. The relative importance of the engagement team’s complexity assessment for each of the characteristics to the overall complexity conclusion will differ across entities based on the specific facts and circumstances.

1. Single Entity—Moderately complex IT environment

Family owned, single entity ABC Limited started as a small business with a non‑complex IT environment. As the business grew, management established an IT function that implements and manages applications, including managing an ERP used for financial reporting.

The illustrative scenario described below highlights how the characteristics of an entity’s IT environment, and our assessment of complexity, might vary based on the entity’s IT strategy implemented to address the IT needs of a growing business.

The following characteristics for the entity were identified as indicators of a “moderately complex” or “complex” IT environment. These indicators were the basis for the engagement team forming an overall conclusion on the level of complexity of the entity’s IT environment, based on the engagement team’s professional judgment, including consideration of input received from IT Audit.

|

Characteristic |

Indicators of a Moderately Complex IT environment |

Indicators of a Complex IT environment |

Engagement team’s complexity assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Automation |

|

|

While sales are initiated on the entity’s online customer ordering portal, orders are manually reviewed by comparing the customer name and account number to an authorized customer list before the order is processed. This partial level of automation is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

|

Reliance on system‑generated reports |

|

|

The majority of reports are standard, however, use of configured reports for significant FSLIs is more indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Customization |

|

|

No automated interface between the online customer ordering portal and the ERP. The customized interface between the online customer ordering portal and the WMS only gives an indication of quantity of items in stock and cannot change the inventory quantities in the entity’s perpetual inventory records. The nature and extent of customization is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

|

Business model |

|

|

Significant proportion of revenue originates from customer orders placed online. The web‑based access and complex security models used for cybersecurity controls is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

| Level of change |

|

|

A limited level of change is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Emerging Technology |

|

|

The proposed move to a new WMS and use of cloud‑based ERP is likely to impact the complexity assessment when the implementation activities begin. At this point, the lack of emerging technology is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Overall Engagement Team Assessment | A combination of characteristics that were assessed to be indicative of a moderately complex IT environment have been identified for this entity. Based on the engagement team’s judgment, including discussion with IT Audit, overall consideration of the above characteristics and assuming there are no significant changes in the IT environment up to the balance sheet date (e.g., the WMS software is not implemented and cloud services have not started to be used), the engagement team would likely conclude the entity has a moderately complex IT environment. | ||

|

Use of IT Audit (based on OAG Audit 3102 policy) |

IT Audit are likely to be involved with the audit of this moderately complex IT environment. The level of involvement planned by the engagement leader and IT Audit personnel may include:

|

||

2. Group‑Wide—Complex IT environment

The head office for a large multinational group has a centralized, specialist IT function that implements, hosts and manages group‑wide applications, including managing a complex ERP used for most aspects of financial reporting. The group financial reporting processes include multiple IT dependencies and ITGCs relevant to the group‑wide applications are designed, implemented and operated at the head office. Component personnel are not able to customize or configure group‑wide applications, including relevant IT dependencies and are only responsible for ensuring local users are appropriate and complying with relevant group‑wide policies. In addition, component personnel are responsible for managing any locally purchased vendor‑developed software. In this example the engagement team’s complexity assessment may be as follows:

Group‑wide understanding and assessment

|

Characteristic |

Indicators of a Moderately Complex IT environment |

Indicators of a Complex IT environment |

Engagement team’s complexity assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Automation |

|

|

Highly automated processes are indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Reliance on system‑generated reports |

|

|

The large number of customized reports is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Customization |

|

|

The complex ERP with significant customization and complex interfaces is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Business model |

|

|

IT is highly integrated into the group business model with complex business processes and high reliance on technology. This is indicative of a |

| Level of change |

|

|

The frequent substantial updates to applications are indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

| Emerging Technology |

|

|

The group’s centralized IT adoption of emerging technology is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

| Overall Engagement Team Assessment | Each of the characteristics were assessed to be indicative of a complex IT environment for this entity. Based on the engagement team’s judgment, including discussion with IT Audit, overall consideration of the above characteristics and assuming there are no significant changes in the IT environment up to the balance sheet date, the engagement team would likely conclude the entity has a complex IT environment. | ||

|

Use of IT Audit (based on 3102 Policy) |

IT Audit is to be involved with the audit of this complex IT environment. The level of involvement planned by the engagement leader and the IT Audit personnel may include:

|

||

The following examples illustrate that:

-

Group and component entities that share the same, or similar characteristics are likely to have the same complexity of IT environment (as illustrated by component A, below)

-

Group and component entities that do not share the same, or have significantly different characteristics are likely to have different complexities of IT environment (as illustrated by component B, below)

Component A

The group engagement team’s assessment of complexity may not necessarily cause us to conclude that all components in the group have a complex IT environment. While there is potential for similar aspects of the IT environment across the group, there may be some aspects of the IT environment that have different levels of complexity across components. Each component engagement team auditing the financial information of the component, will need to assess the complexity of the IT environment for the component(s) for which they are responsible.

|

Characteristic |

Indicators of a Moderately Complex IT environment |

Indicators of a Complex IT environment |

Engagement team’s complexity assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Automation |

|

|

The use of integrated group‑wide application for complex automation is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Reliance on system‑generated reports |

|

|

The reliance on complex configured reports is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Customization |

|

|

While the component entity cannot alter SAP, the SAP version used by the component is still complex and customized. This is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

|

Business model |

|

|

The limited use of highly integrated applications along with the moderately complex business model and a small volume of operations reliant on technology is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Level of change |

|

|

The quarterly changes applied to the applications used by the component is indicative of a complex level of complexity. |

| Emerging Technology |

|

|

The limited use of emerging technologies is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Overall Engagement Team Assessment* |

The majority of assessments for each characteristic were assessed to be complex for this entity. Based on the engagement team’s judgment, including discussion with IT Audit, overall consideration of the above characteristics and assuming there are no significant changes in the IT environment up to the balance sheet date, the engagement team would likely conclude the entity has a complex IT environment. |

||

|

Use of IT Audit (based on OAG Audit 3102 Policy) |

IT Audit is to be involved with the audit of this complex IT environment. The level of involvement planned by the engagement leader and the IT Audit personnel may include:

|

||

* It is the responsibility of the recipient OAG component auditor to assess the relevance and impact of any information communicated on their audit strategy and plan.

Component B

|

Characteristic |

Indicators of a non‑complex IT environment |

Indicators of a Moderately Complex IT environment | Indicators of a Complex IT environment |

Engagement team’s complexity assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Automation |

|

N/A |

N/A |

Component B does not use the complex group‑wide automation. The simple calculations and low volume of data inputs is indicative of a non‑complex level of complexity. |

|

Reliance on system‑generated reports |

|

N/A |

N/A |

Use of standard reports is indicative of a non‑complex level of complexity. |

|

Customization |

|

N/A |

N/A |

Use of non‑complex commercial software, rather than the complex group instance of SAP, is indicative of a non‑complex level of complexity. |

|

Business model |

N/A |

|

N/A |

Component B’s business model does not use the highly integrated applications used by the group but does rely on some technology integration. This is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Level of change |

|

|

N/A |

The manual / traditional way component B handles group changes is indicative of a moderate level of complexity. |

| Emerging Technology |

|

N/A |

N/A |

Absence of emerging technology use is indicative of a non‑complex level of complexity. |

| Overall Engagement Team Assessment |

The majority of assessments for each characteristic were assessed to be noncomplex for this entity. Based on the engagement team’s judgment, and overall consideration of the above characteristics and assuming there are no significant changes in the IT environment up to the balance sheet date, the engagement team would likely conclude the entity has a noncomplex IT environment. |

|||

|

Use of IT Audit (based on OAG Audit 3102 Policy) |

Where the assessment of the IT environment is non‑complex, there is no requirement to use IT Audit * IT Audit could still be used in a consulting or coaching role to support the engagement team if this would be effective and efficient. This may include:

|

|||

* It is the responsibility of the recipient component auditor to assess the relevance and impact of any information communicated on their audit strategy and plan.

Group‑Wide—Moderately Complex IT environment

The group operates in multiple industries and, at the group level, the financial reporting processes are limited to consolidation and treasury processes. There are four components that will be undergoing full scope audits, each is run as a separate legal entity with a distinct IT environment from any other entity in the group. In this scenario, it is possible that the group engagement team would likely conclude that the group entity has a moderately complex IT environment based on the circumstances, regardless of the complexity of each component’s IT environment.

Each component engagement team would need to perform an individual assessment of the complexity of the IT environment for each component. Component IT environments could individually be assessed to be complex, moderately complex or non‑complex based on the understanding of each individual IT environment.

Complex IT environment with Non‑Complex Applications In Scope