Manuel de la vérification annuelle

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

7011.1 Audit guidance for specific financial statement areas

Dec-2023

In This Section

Substantive evidence for revenue

Substantive evidence for income statement accounts other than revenue

Substantive evidence for revenue

OAG Guidance

Importance of Revenue

Revenue is often one of the most significant FSLIs included in the financial statements of an entity, regardless of industry, size or geographic location. Revenue also affects many other significant FSLIs, such as cost of sales and accounts receivable, as well as overall profitability, and the application of accounting principles for the recognition and measurement of revenue can be complex. Internal and external stakeholders often cite changes in revenue when making important decisions that impact the business. Thus, our methodology is necessarily different for revenue than for other income statement accounts because:

-

Financial statement users typically ascribe more importance to revenue.

-

Auditing standards include a presumption of fraud risk in regard to revenue recognition.

-

In certain situations, auditing the balance sheet accounts related to revenue will not address whether all sales transactions have met the revenue recognition criteria.

Audit risk associated with revenue may be affected by changes in

- the business and organization of the entity,

- market and regulatory conditions,

- the interpretation and application of revenue recognition principles,

- the inherent and control risks associated with the entity’s revenues.

We therefore develop an audit plan that incorporates controls and/or substantive audit procedures to the extent deemed necessary based on the results of our assessment of the risk of material misstatement for relevant assertions.

Risk Assessment

The accounting for revenue may be complex, resulting in higher inherent risks of material misstatement from unintentional errors for certain assertions. Further, the assessed level of inherent risk may vary among different types of revenue transactions or assertions, or be different to that determined in prior years due to changes in the entity’s business and markets, operations, accounting principles and financial position. Accordingly, performing a risk assessment as described in OAG Audit 5040 is essential to our audit planning and execution. The assessment of risk is performed at the assertion level for significant revenue streams and reflects the characteristics, including size and complexity, of each revenue stream.

One aspect of the risk assessment process for revenue is to develop an understanding of the accounting policies and relevant accounting framework management utilizes to record revenue. Our understanding of the revenue streams would consider characteristics that may impact the complexity of revenue recognition and inherent risk, and ultimately our audit approach. Some factors to consider may include

- gross versus net income statement treatment;

- multiple deliverable arrangements;

- sales incentives;

- customer acceptance provisions;

- post-delivery obligations;

- exchanges;

- percentage of completion arrangements, including construction‑type and certain production‑type contracts;

- unbilled revenue and deferred revenue;

- sale of software, including embedded software;

- leasing revenue arrangements;

- research and development revenue arrangements;

- separately priced product maintenance and extended warranty arrangements;

- barter transactions;

- side-agreements;

- bill and hold or ship‑in‑place agreements;

- up front / advance fees;

- sales of future revenue;

- collaboration agreements;

- intellectual property;

- seller provided financing and guaranteeing arrangements;

- cancellation or refund rights;

- industry specific considerations.

In addition to inquiries of management and those responsible for financial reporting, we may also obtain information or a different perspective in identifying risks of material misstatement related to revenue through our risk assessment analytics, inquiries of others within the entity and sources of information external to the entity, such as analyst reports, industry reports and peer company analyses.

In addition to the risk of material misstatement due to error, there is a rebuttable presumption of a fraud risk related to revenue recognition. A relatively straight forward revenue recognition accounting policy may not present more than a normal risk of material misstatement due to error, but the mere lack of accounting complexity and/or the straight forward nature in which revenue transactions are processed does not alone provide sufficient rationale to conclude the risk of material misstatement due to fraud is not present. Accordingly, we need to evaluate which types of revenue, revenue transactions or assertions are impacted by such risks, as discussed further in OAG Audit 5509.

As a result of the risk assessment procedures outlined above we would normally identify at least the following risks in relation to revenue:

-

Significant risk of material misstatement due to fraud in revenue recognition tailored based on the specific circumstances of the engagement (unless the risk is rebutted).

-

Risk of material misstatement due to error, assessed as normal, elevated or significant.

Additional considerations—assessing risk of fraud in revenue recognition

|

Note: Set out below are additional considerations that may be applicable when assessing the risk of fraud in revenue recognition and determining an appropriate audit response to the risk. Our approach depends on engagement specific circumstances and our assessment of fraud risk, including the nature and characteristics of revenue and consideration of the components of fraud (i.e., incentives, opportunities and rationalization). To the extent that facts and circumstances of a particular audit engagement differ from those in the scenario below, including additional facts and circumstances, the judgments of the engagement team may differ from those reached in this scenario. For each engagement, we determine the most effective and efficient audit response to the risk of fraud in revenue recognition, considering the results of our fraud risk assessment and all other engagement specific circumstances. CAS 240 requires an assessment of the risk of fraud at the assertion level for classes of transactions. In order to focus our audit effort appropriately, we identify and articulate clearly which assertion(s) is/are relevant and why and our view as to how we believe fraud might be perpetrated in each of the respective revenue streams. Our audit documentation needs to reflect the specific engagement circumstances and the rationale for the judgments made. |

When the audit is performed on an entity which has high volumes of individually low value, non‑complex revenue transactions (e.g., a single performance obligation with recognition at a point in time) and:

-

Our planned approach includes testing of revenue transactions that are individually significant by nature or monetary value (if any); and

-

We conclude that appropriate controls over revenue transactions have been designed and implemented,

we might conclude that material misstatement due to fraud resulting from recognition of these low value, non‑complex transactions is less likely, given how many inappropriate transactions would need to be posted to amount to a material misstatement. Note that such a conclusion about the risk of material misstatement due to fraud would not eliminate the need to assess the risk of material misstatement due to error and the need to perform appropriate audit procedures to address the risk in accordance with this section.

In such situations, we might conclude that the material fraud risk related to revenue recognition is isolated to the posting of fraudulent revenue journal entries directly into the general ledger, consolidation entries and topside entries.

In these circumstances, sufficient evidence to address the risk of fraud in revenue recognition may be obtained through the following tests:

-

Performing testing of journal entries and other adjustments to revenue in accordance with OAG Audit 5509, as part of the response to the risk of management override of controls;

-

Performing substantive testing of the year end reconciliation between the sales subledger and general ledger, including tests of details for any significant reconciling items;

-

Performing tests of details over consolidation entries to address the risk of material misstatement in accordance with OAG Audit 2351; and

-

Performing tests of details on any topside entries made directly to the financial statements, as required by CAS 240.

Developing a Revenue Testing Strategy

General considerations

We develop a testing strategy that is appropriate based on our understanding of the revenue and receivables business process and controls, and the assessed level of risk for relevant assertions with respect to revenue, as determined and documented as part of the risk assessment process. The testing strategy and audit plan is tailored to reflect the particular circumstances of the entity and nature of the revenue.

We would normally perform specific procedures to address the risk of material misstatement for particular relevant assertions due to fraud in revenue recognition, which are responsive to the specific fraud risk factors that were identified as being relevant to the audit. These procedures are generally incremental to those that would be performed to address the risk of material misstatement due to error, however depending on the nature of the risk and the planned audit response they may involve leveraging the procedures performed to address the risk of material misstatement due to error. For further discussion on the risk of misstatement due to the fraud in revenue recognition, refer to OAG Audit 5506.

CASs and OAG Audit recognize that in designing the procedures to be performed, we need to consider the reasons for the assessment of the risk of material misstatement for relevant assertions. In relation to revenue this often involves identifying the revenue streams and developing a testing strategy accordingly. However, oftentimes we are able to further break down these revenue streams according to their risk characteristics. Revenue streams with different characteristics (e.g., different processes and controls, different risks) would generally be considered separate populations and therefore we need to perform procedures to address the relevant assertions with regards to each of these separate revenue streams, as appropriate. In many cases, we may consider there is less risk associated with revenue transactions settled during the year than unsettled transactions outstanding as of the date of the financial statements, as explained further in this section.

OAG Audit discusses the following procedures, or combinations thereof to be utilized in developing a response to the identified risks in relation to revenue:

-

Tests of controls (OAG Audit 6050)

-

Substantive analytical procedures (OAG Audit 7030)

-

Substantive test of details:

- Targeted testing (OAG Audit 7042)

- Two-step revenue approach (see guidance below “Two Step” Approach and OAG Audit 7044)

- Audit sampling (OAG Audit 7044)

- Accept-reject testing (OAG Audit 7043)

We obtain an understanding of the controls over revenue and determine whether those controls have been implemented, and consider whether testing of such controls would be effective and efficient. The level of controls reliance obtained and the resulting nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures performed is based on the evidence from controls with respect to each relevant assertion for the applicable revenue stream. Regardless of the level of controls reliance, we ordinarily need to perform substantive procedures for each relevant assertion in revenue, as explained in OAG Audit 7011. For example, if cut‑off is considered a relevant assertion, irrespective of relevant cut‑off controls that we test and find to be operating effectively, ordinarily we still need to perform substantive procedures to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence for this assertion.

For revenue streams and/or assertions that do not represent a significant risk, disaggregated revenue analytical procedures designed to provide substantive audit evidence and executed in accordance with OAG Audit 7030 may be both an effective and efficient audit procedure to reduce audit risk for those particular revenue streams and/or assertions to an appropriately low level. When using substantive tests of details, targeted testing is our preferred approach as it provides the opportunity to exercise significant judgment over the items to be tested.

In situations where the characteristics of a revenue stream or underlying testing population require the application of complex accounting principles, we further tailor the nature of our audit procedures and the type of evidence obtained to be able to evaluate whether the specific revenue recognition criteria have been met, and whether revenue is being recorded in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework.

It is also important to understand the possible relationship that evidence obtained in procedures performed over other account balances may have with respect to evidence to be obtained for the assertions relevant to revenue. For example, accounts receivable confirmations may also provide evidence as to the occurrence of sales transactions that have been billed, however they generally do not provide evidence with respect to the occurrence of revenue for the entire period under audit. Therefore, we would need to perform substantive procedures over revenue in addition to the procedures over the accounts receivable and other related accounts. Where we applied targeted testing to less than the entire account balance we need to consider the sufficiency of audit evidence related to the untested revenue balance in accordance with OAG Audit 7042 and we need to document the basis for our conclusion.

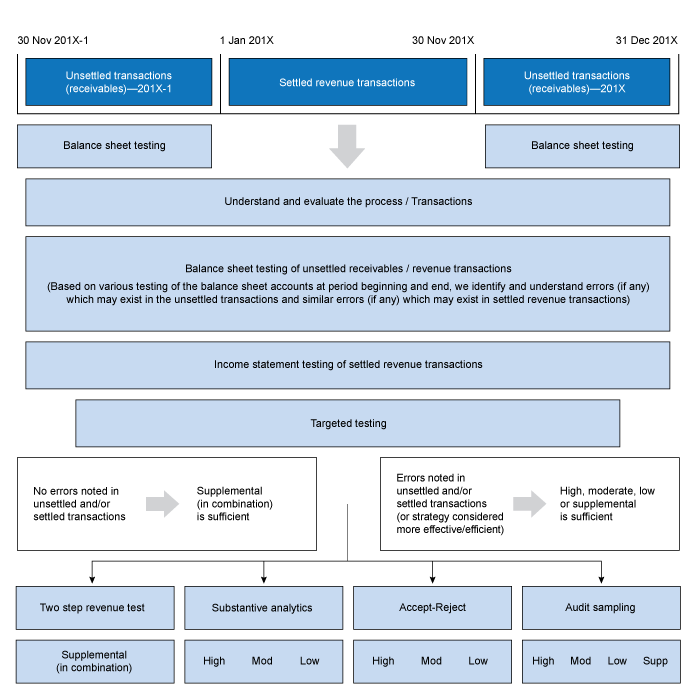

The chart below briefly summarizes potential procedures, or combinations thereof, that can be utilized when developing a response to the identified risks in relation to revenue for an entity with a 31 December year end and all accounts receivable being collected within 30 days. This chart is solely provided for illustrative purposes and does not intend to depict a decision tree for determining an effective and efficient testing strategy. We need to consider the engagement specific facts and circumstances and we need to consider specific guidance provided in the relevant sections of OAG Audit Manual to determine an appropriate audit plan:

Based on various testing of the balance sheet accounts (e.g., receivables confirmation and/or liquidation procedures, journal entry testing, etc.) we identify and understand errors (if any) which may exist in the unsettled receivables/revenue transactions and which may also be indicative of similar errors (if any) in the settled transactions. Generally, settled transactions are considered to have a lower likelihood of error, because by submitting payment the customer has agreed to and met the terms of the sales transaction. In contrast, unsettled transactions are those for which the customer has not submitted payment, and therefore the existence and terms of the sales agreement have not been subjected to the customer’s processes for review and approval of related payment. In selecting items to test it may be appropriate to separate sales transactions between the unsettled (i.e., those individual sales transactions that are recorded in accounts receivable as of the balance sheet date) and the settled (i.e., those individual sales transactions for which a payment has been received from the customer and appropriately applied to the receivable account). Taking into account our testing of unsettled receivables/revenue transactions, we then obtain further audit evidence for settled revenue transactions, considering our understanding of the revenue/receivables business process, commercial terms and conditions related to products and services sold and expected level of controls reliance. There are circumstances where disaggregation of revenue between settled and unsettled transactions may not be easily achieved and/or may not be an appropriate testing approach. In most cases, targeted testing may not provide sufficient substantive evidence if the revenue transaction being tested are numerous and small. Therefore we may need to perform further substantive audit procedures over revenue after considering, among other things, the extent of control testing performed. This can be accomplished by using the two step revenue test, accept‑reject testing (for certain assertions), substantive analytics, audit sampling, or a combination thereof depending on the level of assurance needed for the relevant assertions being tested.

Thus, from the results of our testing of the unsettled transactions we can determine the extent of sufficient appropriate evidence that is necessary for the remaining settled transactions. Our further substantive testing therefore would focus on the population of settled transactions, not the whole revenue population for the period. Using the chart above as an example, we may apply audit sampling to the population of settled revenue transactions that occurred during January–November 202X. Evidence for the revenue transactions that occurred in December 202X would be provided by the accounts receivable testing (providing that accounts receivable testing addresses the relevant assertions related to revenue transactions).

In determining whether the level of evidence over the settled revenue transactions is sufficient, we also consider the results of the procedures performed over the unsettled transactions and whether any misstatements identified are indicative of a systematic error that is likely to impact settled revenue transactions.

Testing of accounts receivable balances (unsettled transactions) may provide evidence over some relevant revenue assertions (such as occurrence, cut‑off, and in some instances accuracy). For example, we may obtain a confirmation from the customer that includes details of the transaction, such as invoice number, purchase order number, quantity, sales price, terms and conditions and/or other relevant evidence or we may perform alternative procedures by obtaining the purchase order, invoice and shipping documents. Therefore, we consider the nature of testing performed over accounts receivable and determine whether it is necessary to supplement or vary the accounts receivable tests to obtain the desired evidence over the assertions relevant to our revenue testing.

Examples of Revenue Testing Strategies

We develop and perform specific audit procedures that separately address the identified risk of fraud in revenue recognition on our engagements. In respect of the risk of material misstatement due to error, we utilize one or a combination of testing procedures, based on the specific circumstances of the engagement, balancing the level of evidence necessary and the effectiveness and efficiency of the procedures to address the risk.

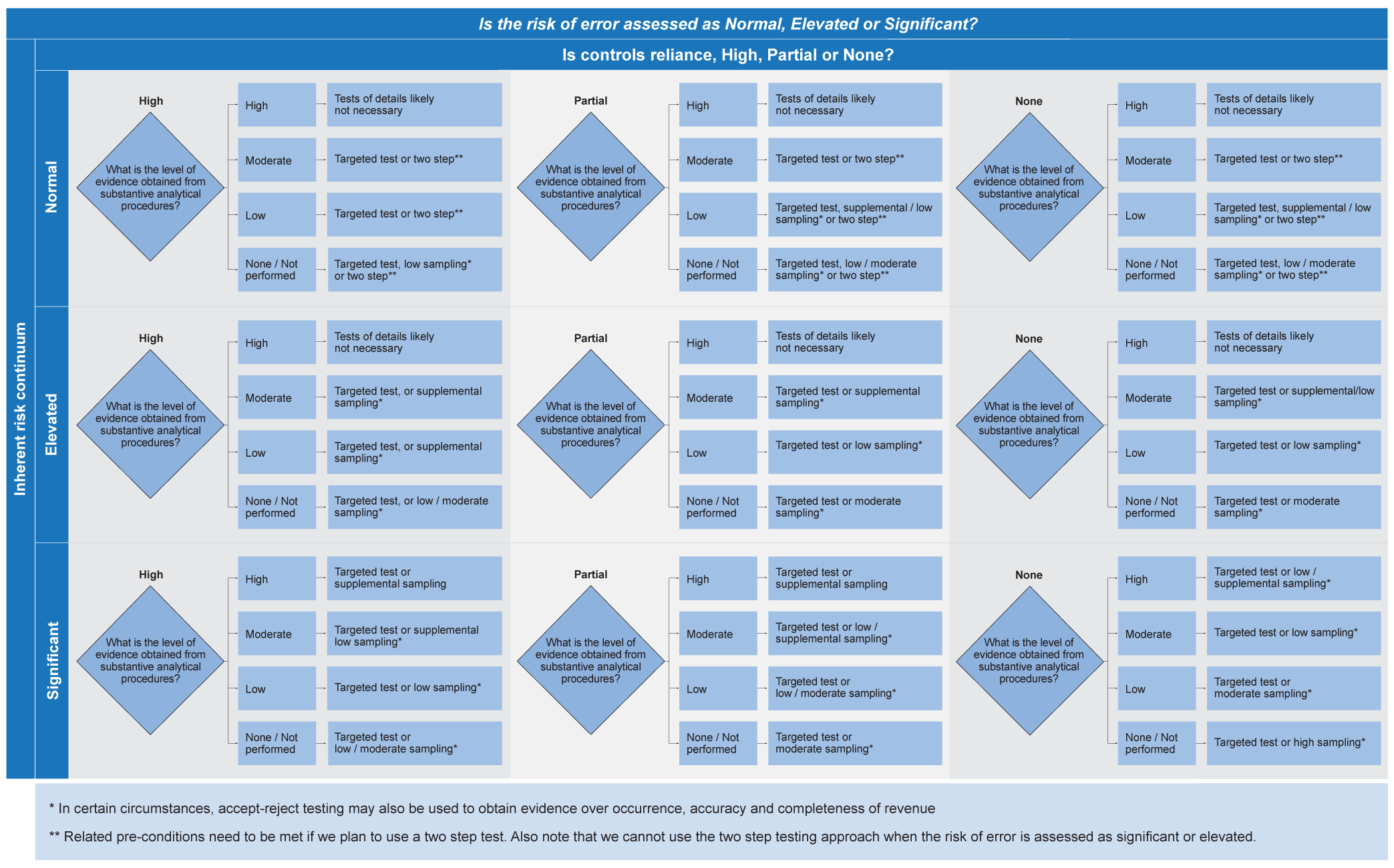

The following chart illustrates the general relationship between the evidence that would be obtained from a combination of controls testing, substantive analytical procedures and tests of details. This is solely provided for illustrative purposes and we would need to determine the most effective and efficient testing strategy, depending on the circumstances of the audit. We consider the spectrum of the risk of material misstatement. Where the risk of material misstatement is assessed at the higher end of the spectrum, the level of evidence necessary from tests of details would increase. As noted in the guidance above Developing a revenue testing strategy, we also need to perform specific audit procedures to address the risk of fraud in revenue recognition, as appropriate.

As noted in OAG Audit 7011, if we are unable to place reliance on controls, the information used as the basis for analytical procedures may be unreliable and accordingly, the analytical procedures will not be effective. In that case it may be inefficient to perform substantive analytical procedures and we plan to perform tests of details.

We may perform various types of tests of details to achieve the necessary level of substantive evidence over revenue. For example, when we need a Low level of evidence from detailed testing over revenue, this can be achieved in a number of ways:

- Two step test (when the related pre‑conditions have been met).

- Targeted test combined with supplemental non‑statistical sampling or statistical sampling.

- Audit sampling at the Low level of evidence.

The chart below provides illustrative examples of substantive procedures (and combinations thereof) that we can perform to achieve the necessary level of evidence, as illustrated on the diagram in the guidance above Developing a revenue testing strategy. This is solely provided for illustrative purposes and we would need to determine the most effective and efficient testing strategy, depending on the circumstances of the engagement.

Consider the following in relation to the testing strategies examples above:

-

Where we plan to use the two step revenue test, we need to consider if the related pre‑conditions have been met (see guidance below “Two Step” Approach).

-

Evidence obtained from controls testing affects the extent of substantive testing we need to perform. For example, the extent of targeted testing we need to perform to obtain sufficient evidence may be lower when we have high controls reliance, as compared to partial controls reliance.

-

When we plan to perform substantive analytics over revenue to achieve low or moderate level of evidence and certain pre‑conditions are met, we may use thresholds that could exceed performance materiality, as explained in OAG Audit 7033.2.

-

Substantive tests over revenue (targeted testing, non‑statistical sampling, statistical sampling, etc.) would be primarily focused on the revenue transactions settled during the period. Substantive evidence for the unsettled revenue transactions would normally be obtained from leveraging testing of accounts receivable.

-

Decisions on whether we have sufficient appropriate audit evidence are a question of judgment, weighing the materiality and risk factors against the quality of the evidence provided, the nature, timing, extent of our testing and its results. When making these decisions regarding sufficiency of evidence we consider that certain procedures may be more appropriate for some assertions than others.

-

There may be a number of revenue testing strategies that would be effective on a particular engagement. Therefore, consider the options available, and determine which strategy is more appropriate given the engagement’s particular facts and circumstances.

“Two Step” Approach

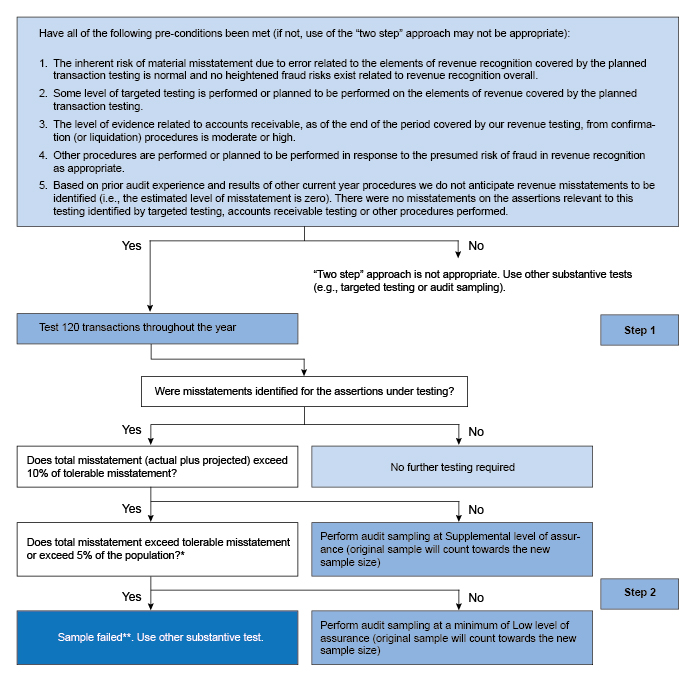

Depending on the inherent risks of material misstatement related to revenue and substantive evidence obtained from accounts receivable confirmation (or liquidation) and fraud procedures, we may apply a “two step” approach to detailed testing of a selection of revenue transactions in certain situations. For details please see guidance below:

-

Step 1: When certain pre‑conditions, as described below, are met, test 120 revenue transactions throughout the period.

-

Step 2: Evaluate if further evidence is necessary. If no misstatements were identified, further testing would not be required. When misstatements were identified, perform audit sampling at an appropriate level of assurance.

This “two step” approach is appropriate when:

-

The inherent risk of material misstatement due to error related to the elements of revenue recognition covered by the planned transaction testing is normal (i.e., is not elevated, or significant) and no heightened fraud risks exist related to revenue recognition overall (i.e., no specific fraud risks beyond the presumed risk of fraud in revenue recognition);

-

Based on cumulative audit experience and results of other current year procedures we do not anticipate revenue misstatements to be identified (i.e., the estimated level of misstatement is zero). Note: Not every exception is necessarily a misstatement or an indicator of misstatement. Consider what would constitute a misstatement in relation to our revenue test objectives and requirements of the applicable financial reporting framework. For example:

-

A sales return or bad debt would generally not be considered a revenue misstatement when the entity has properly accounted for such items;

-

-

When performing testing over revenue we might anticipate differences whereby amounts recorded in the general ledger could ultimately be settled at less than full value based on anticipated normal or routine credits or adjustments. Since adjustments of recorded gross revenue transactions, in any form, can be indicators of potential misstatements, it is therefore common as part of an overall revenue testing strategy for us to perform procedures over these adjustments to conclude if they are valid and appropriate, or whether they are indicators of potential misstatements. Where the testing of these adjustments indicates that they are valid and appropriate, they would typically not be considered misstatements for the purposes of the two step approach;

-

If an account is adjusted via credit memo for a pricing error, it would be considered an indicator of potential misstatement in gross revenue, and as such it may be inconsistent to use the two step approach in light of that finding. If however errors have been corrected before we perform our testing and we are able to ascertain that the entity has appropriately accounted for such pricing errors as a result of controls that have been in operation throughout the period, the use of the two step approach may still be possible. Further, examination of credit memos issued subsequent to period end may provide additional evidence regarding the likelihood of potential misstatement in revenue;

-

Some level of targeted testing is performed on the elements of revenue (e.g., revenue streams) covered by the planned transaction testing;

-

The level of evidence related to accounts receivable, as of the end of the period covered by our revenue testing, from confirmation (or liquidation) procedures is moderate or high; and

-

Other procedures are performed in response to the presumed risk of fraud in revenue recognition as appropriate (e.g., testing of journal entries, unpredictable audit procedures, corroboration of unusual account combinations associated with general ledger revenue account postings) targeted at the existence / occurrence and accuracy / valuation of revenue.

If the above criteria are satisfied, we can initially limit the number of revenue transactions selected for testing throughout the period to 120. If no misstatements related to our test objectives are identified from our accounts receivable confirmation (or liquidation), targeted fraud, or revenue transaction testing procedures for the relevant assertions under testing, further revenue transaction testing would not be required.

If revenue misstatements arise from revenue transaction testing procedures, accounts receivable confirmation (or liquidation), targeted fraud testing in relation to the relevant assertions covered by the “two step” approach, the Non‑statistical Sampling template or statistical Sampling template within the Test of Details template needs to be utilized to complete a sample (i.e., “two step”) at an appropriate level of assurance, and tolerable and estimated misstatement, based on the number and amount of the misstatements identified. If actual misstatements plus the projected misstatement based on results of our initial test selection exceed 10% of tolerable misstatement, an audit sample at a minimum at the Low level of assurance needs to be performed, because the actual misstatement rate would not allow us to accept the results of a sample at the Supplemental level. In such circumstances we would also need to consider if the account may be materially misstated and whether performing further audit sampling (at Low or higher levels of assurance) is appropriate. However, if no further errors are expected and the Supplemental level continues to be an appropriate level of assurance, the Non‑statistical Sampling or the statistical Sampling template within the Tests of Details template would be completed.

Finally, if identified misstatements are indicative of potential fraud, our fraud risk assessment and sufficiency of planned substantive evidence overall need to be reassessed.

Depending on the relationship of tolerable misstatement to the revenue population to being tested and the number of revenue streams, taking into consideration engagement circumstances (e.g., coverage obtained from targeted testing, level of evidence desired from audit sampling etc.), it is possible that an audit sample at the Supplemental or other assurance levels of the revenue account balance could result in a sample size less than 120. In such cases, it would be more efficient to perform an audit sampling at the appropriate level of evidence, rather than applying the “two step” approach. For example, for a client with 3 revenue streams and performance materiality reflecting 0.5 percent of revenue, the total number of items to be tested under the Two Step Revenue Approach (in addition to the target test) would be 360 (120 transactions x 3 revenue streams), whereas a non‑statistical sample or statistical sampling at a low level of assurance may require 160 transactions. See OAG Audit 7044 for further details on the impact of materiality disaggregation when using non‑statistical sampling.

The following chart represents a summary illustration of the “two step” approach described above.

*Even if the total misstatement is less than tolerable misstatement, we still need to appropriately consider sampling risk or the risk that our sampling results might underestimate the actual misstatement in the population tested.

**Consider requesting that the entity conducts additional testing that we can audit to support the recorded amount, before we expand our testing.

For guidance regarding the theory supporting the “two step” approach, refer to OAG Audit 7044.

Group audit considerations

The guidance above is applied to each revenue testing population. For example, if revenue transaction testing is planned at 5 components within a consolidated group 120 transactions would be tested at each (assuming the criteria described above were met at each component). See OAG Audit 2330 for general guidance on determining the audit strategy and plan on group audits.

Accounts Receivable Testing—Timing

The requirement discussed above to obtain a moderate or high level of evidence from our testing of accounts receivable could also be satisfied by performing confirmation (or liquidation) procedures at an interim date and performing an appropriate level of substantive roll‑forward procedures to extend our interim audit conclusions to the balance sheet date at the desired moderate or high level of evidence.

Sampling at the Supplemental Level of Assurance

The criteria described above apply when testing of revenue transactions is initially limited to 120. If instead an audit sample at the Supplemental level of assurance is executed, the chart included in OAG Audit 7044 would be considered in determining the appropriate level of substantive evidence from other audit procedures, including those related to accounts receivable.

Targeted Testing—Level of Coverage Necessary to Apply the Supplemental Level of Assurance

As discussed in more detail in OAG Audit 7044.1, the objective is to obtain evidence from other substantive audit procedures that when combined with the evidence obtained from a sample performed at the Supplemental level of assurance provides the overall amount of substantive evidence considered appropriate in the circumstances. Further, in order to satisfy the requirement that the Supplemental sample is not the only direct test of the account, some targeted test and/or unpredictability selections need to be made. However, there is no minimum number of selections, or coverage from target testing—whether from dollar or risk‑based targets—required to achieve that objective.

The following FAQs supplement the guidance above.

1. One of the pre-condition for the two step revenue approach is that some level of target testing is performed. Is the target testing in addition to or part of the 120 sample size?

The target testing is in addition to the 120 sample size. The purpose of target testing is to select items to be tested based on some characteristic. Teams may choose to select specific items from the population that may include:

-

High value or all items over a certain amount, or

-

Items with specific risk characteristics

The audit manual is explicit that there is no minimum coverage level required either through risk based or dollar target testing. Identification of items to target test may become difficult if the population is homogeneous but it would not be considered acceptable to test no items. There is a common misconception that target testing requires testing of a certain dollar value, so teams are often looking for large dollar value items, whereas target testing can also focus on specific risk characteristics. Some examples of specific risk characteristics include target Top 5 sales (even though those top 5 sales may not be very significant from a materiality perspective), sales made to new customers, or sales made to customers in a specific geographic location or from a particular location that the client has. As a result, an engagement team may decide that target testing a small number of the largest transactions or a few transactions with a certain risk characteristic is sufficient to meet the requirement of performing some level of target testing.

2. Can I count my cut‑off testing as target testing in order to meet the condition for the two step revenue approach?

No. Target Testing has to cover all the assertions that the population of 120 were designed to cover. Since cut off is not covering all of the assertions, it would not qualify.

3. Where accounts receivables are not material because sales are received almost immediately (i.e. retail or where A/R can be material but not significant in comparison to sales – i.e. $20m in receivable for $300m in revenue) and if the team has rebutted the requirement for accounts receivable confirmations is it sufficient to obtain a moderate amount of comfort from liquidation type procedures?

The moderate to high level of assurance over accounts receivable can be obtained through any combination of audit procedures the team considers appropriate. Confirmations are not required to use the two step revenue test.

4. For engagements that do not have an account receivable FSLI, does this mean that the two step revenue approach cannot be used as the pre‑condition, that the level of evidence related to accounts receivable, as of the end of the period covered by our revenue testing, from confirmation (or liquidation) procedures is moderate or high, hasn’t been met? For example in real estate a home developer collects all cash on close therefore the account receivable balance is immaterial.

It may be appropriate for teams to still use the two step revenue approach even though the client has no accounts receivable. In these cases the team would be doing adequate procedures to get a moderate or high level of assurance to confirm that the accounts receivable balance is zero. Teams with clients of this nature should also consider getting a moderate to high level of assurance on any liabilities created through the revenue cycle (deferred revenue, deposits or pre‑payments, etc.).

5. Does a moderate level of assurance on accounts receivable mean that I have to do a moderate audit sample on my confirmations?

No. If you are looking for a moderate level of comfort over accounts receivable, you can get that comfort through test of controls, target testing or audit sampling. For example, if you have no controls comfort, but you have a target test that covers 90% of your balance; you may not need to do any additional testing. Another example is that you may have a target test and obtained coverage over 50% of the balance and you might consider a supplemental audit sample over the remainder of the balance.

6. We are looking to perform an accounts receivable (A/R) liquidation computer‑assisted audit technique (CAAT) on the October 31 balance (December fiscal year end and days outstanding are approximately 60 days). If we test the roll‑forward of sales and receipts in the Nov‑Dec stub period is it enough for moderate comfort to apply the 2 step revenue approach?

The two-step approach requires a moderate level of assurance to be obtained over accounts receivable.

Generally speaking the use of the A/R Liquidation CAATs on a balance will result in a moderate to high level of assurance over the balance being tested. If a team tests the A/R balance at an earlier date to a moderate level of assurance and then performs adequate roll‑forward testing over the intervening period (through a combination of controls, substantive analytics, target testing, audit sampling or a CAAT) this would meet the requirements of the two‑step revenue test criteria.

7. What level of assurance does the two step revenue approach provide?

The 120 sample size is based on the supplemental level of assurance. This is considered appropriate for the revenue assertions of occurrence and transactional accuracy because the risk of error for these two assertions is generally low and a minimal amount of substantive evidence is required to support the audit opinion in this area. These testing techniques are reserved for areas where we do not expect errors and the risk of error is at the balance sheet date (i.e. cut‑off) and therefore don’t require a large amount of evidence for what has occurred during the year.

8. Can we use audit sampling at the supplemental level instead of the two step approach?

Yes – the 120 sample size is a maximum and is based on the supplemental level of assurance. If the sample size under the supplemental level of assurance would be lower than the 120 items in the two step revenue approach, the team should complete the Non‑statistical Sampling template within the Test of Details template to determine the sample size or use the DUS calculator in IDEA.

9. How should the two-step revenue testing approach be applied to different line items or streams of revenue?

The two-step revenue testing approach should be applied separately to each stream of revenue. Teams should ask themselves the following questions when determining which revenue streams should be separated or combined:

-

Are the criteria for revenue recognition consistent (e.g. FOB shipping point versus FOB destination) between the different revenue streams?

-

Are there different risks associated with the different streams of revenue?

-

Are the processes and controls consistent over the revenue streams?

If there is sufficient commonality between the different streams of revenue then the streams can be combined and the sample can be spread across the different streams. However, if an error is identified in one of the streams it will have to be evaluated in the context of all of the revenue included as a part of the sample.

10. When using this two-step approach for revenue testing, can we prorate the sample based on the period that we’re covering?

Yes – if you are sampling 120 items it would be appropriate to select 10 items in each month as long as the volume of transactions is consistent each month during the year.

11. When would you still want to test controls when you are using the two‑step revenue testing approach?

Under the two-step revenue approach there is no requirement to test controls. Teams may want to do it for other reasons – (e.g. client expectation) but it’s not a prerequisite to use the two‑step revenue approach.

Substantive evidence for income statement accounts other than revenue

OAG Guidance

This guidance discusses factors to consider in determining how much audit evidence is enough related to the audit of income statement accounts other than revenue and whether audit sampling is necessary when auditing costs and expenses. We need to follow a coordinated testing plan as provided in OAG Audit and not perform two “separate” audits—controls and balance sheet, and controls and income statement.

This guidance is directed towards the following categories of costs and expenses:

-

Cost of sales (which is derived from the inventory conversion process).

-

Balances derived from the attributes of related balance sheet accounts (e.g., depreciation expense, interest expense, etc.).

-

Balances that represent expenditures adjusted by changes in accruals and estimates (e.g., most payroll, SG&A, and operating expenses, which are derived from expenditure‑based processes, such as accounts payable, payroll and treasury).

We benefit from a fully coordinated audit strategy, because developing audit procedures for each account balance and assertion in isolation, rather than a coordinated set of procedures that together address the various accounts and assertions within a business process, tends to promote inefficiency and over‑auditing. The income statement and balance sheet are fundamentally interrelated and related balances tend to be generated from within common business processes, under common controls, and with common audit objectives that are most effectively and efficiently achieved when planned as a whole.

Note: There may be transactions recorded in the income statement that are large, unusual, and nonrecurring, or costs and expenses that are the basis for recording revenue (e.g., percentage of completion contract costs). In these situations it would be efficient and effective to base our audit strategy towards the income statement account or disclosure and then leverage those procedures to audit the balance sheet accounts, rather than leveraging the audit procedures performed over the balance sheet accounts. This guidance is directed towards those income statement accounts where we will leverage our substantive audit procedures on the balance sheet to influence how much additional testing is needed for the income statement accounts.

Framework

Our methodology on how much audit evidence is required on costs and expenses in the income statement is grounded in these fundamental considerations:

1. Audit objectives for balance sheet and related income statement accounts need to be achieved from a coordinated testing plan.

As explained in OAG Audit 7011, we design and perform one or more substantive procedures for each relevant assertion of each significant FSLI. However, this is not intended to imply that substantive audit procedures need to be applied without regard to audit evidence obtained as part of our testing of a related account, since it is likely that satisfactory audit work has already been performed on related account balances subject to the same or very similar audit objectives. It also means that we do not view each FSLI in the balance sheet or income statement as a unique FSLI to be evaluated for adequacy of audit evidence on a stand‑alone basis.

Procedures applied to balance sheet and related income statement accounts that are part of the same transaction process are interdependent and may be leveraged. By way of example, evidence supporting the completeness, accuracy and existence of an accrued liability or trade accounts payable at the beginning and end of a period contributes to evidence about the completeness, accuracy, and occurrence of related costs and expenses during the period, and tests of controls comprising reperformance or examination of evidence may be dual‑purpose (e.g., they both evaluate the effectiveness of controls and serve as substantive tests). In turn, a satisfactory reasonableness test of an income statement account balance may contribute to evidence that related balance sheet accruals are appropriate.

In other words, we detect material misstatements in amounts recorded as costs and expenses by taking a holistic coordinated transaction cycle approach whereby we: a) Audit the related balance sheet accounts, b) Get comfortable with income statement and balance sheet classifications through our substantive testing (e.g., accept‑reject) or dual purpose testing, c) Address fraud, elevated and significant risks through directed audit procedures targeted for the risk, and d) Evaluate whether the final balances make sense.

2. Costs and expenses are typically not subjected to tests of details, especially by way of audit sampling.

Our audit objectives for amounts recorded as costs and expenses are primarily focused on evaluating whether all expenses incurred have been captured, are recorded in the proper period, and are properly classified and presented on the income statement. Performing audit sampling and testing of expense items to achieve those objectives is an ineffective procedure for the following reasons:

-

We normally approach our audits with the view that liabilities are more likely to be understated or omitted from the accounts than overstated, and that assets are more likely to be overstated than understated. Our audit objectives, therefore, tend to focus on determining that prepaid assets are not overstated and that accrued liabilities are not understated, but without ignoring the possibility that the opposite may occur. Sampling from items recorded won’t address the more prominent audit risk and objective—that all items that should have been recorded have, in fact, been recorded. For example, it will not address period‑end estimates of expenses incurred related to goods or services for which invoices have not yet been received.

-

A misstatement in an expense account is either a misclassification on the income statement or a corresponding misstatement on the balance sheet. We therefore would be able to detect material misstatements in amounts recorded as expenses from a combination of: a) the procedures we apply to the related balance sheet accounts, b) our end‑to‑end cycle‑based controls and dual purpose testing about the proper classification of expenditures and associated attributes, and c) the results of our analytical procedures.

3. Analytical procedures (including risk assessment analytics and overall conclusion analytics) are integral to determining the sufficiency of audit work.

All accounts, at least at the financial statement level, are subjected to risk assessment analytics and overall conclusion analytics. Some accounts are optionally and discretionarily subject to further risk assessment analytics and/or substantive analytics. While risk assessment analytics and overall conclusion analytics may not provide direct substantive audit evidence, they do provide us with valuable audit evidence related to our audit judgments on how much audit evidence we need (i.e. nature, timing and extent of our other procedures). Risk assessment analytics diagnose and direct our attention so we focus our audit testing. Overall conclusion analytics help us to evaluate whether the financial statements “make sense” based on the results of our audit work. They help us in evaluating the proper classification of balances, and they direct us to do more work when account balances (including expense account balances) and financial statement relationships do not make sense in light of the work we have already performed.

Our audit methodology recognizes that certain types of expenses are conducive to the use of substantive analytics as an effective and efficient means of determining their reasonableness, and substantive analytics as a part of an overall audit strategy of controls testing, along with substantive tests of the balance sheet, are encouraged. Those in particular include:

-

Accounts that are highly correlated to revenue (e.g., specific elements of or overall cost of sales, commission expense, sales promotion expenses, etc.).

-

Accounts that are highly correlated to balance sheet accounts or are a function of the terms associated with balance sheet accounts (e.g., interest expense, interest income, depreciation expense, etc.).

-

Accounts that are more highly predictable based on auditable inputs (e.g., payroll expense).

Some accounts or cycles are conducive to other types of risk assessment procedures that might be helpful in informing our judgment that the substantive work we have done on balance sheet accounts is sufficient to detect a material misstatement in a particular business process. Examples of such procedures might be:

-

Scan expense account activity for missing or unusual entries (e.g., monthly cost with only 11 months recorded; large ins and outs.

-

Scan expenditures by vendor or by classification.

-

Scan activity (not just ending balances) in suspense accounts or miscellaneous accounts.

-

Analyze variances against standard inventory costs throughout the year (not just year‑end).

-

Analyze common ratios (see OAG Audit 7035 for examples).

Substantive analytics are not required, nor are the examples of additional risk assessment procedures provided above. Significant auditor judgment is needed when planning the collective audit procedures needed to detect potential material misstatements within a business process. Part of that audit judgment is determining whether other types of analytics, if not already planned, would be part of the testing strategy (in addition to risk assessment and overall conclusion analytics). Note that when we plan to perform substantive analytics over revenue to achieve low or moderate level of evidence and certain pre‑conditions are met, we may use thresholds that could exceed performance materiality, as explained in OAG Audit 7033.2.

Note that this framework is not the same for revenue, where audit sampling or other direct tests is used more frequently. While we can see that these considerations can be applied to revenue in a broad sense, the approach for testing revenue as provided in the auditing standards, and our methodology is necessarily different than for other income statement accounts principally because:

-

Financial statement users typically ascribe importance to revenue as an indicator of growth prospects of the entity and the cash generating nature of an entity’s revenue‑producing activities as a source of funding.

-

The auditing standards include a presumption of fraud risk in regard to revenue recognition.

-

In certain situations, auditing the balance sheet accounts related to revenue will not address whether all sales transactions have met the revenue recognition criteria.

Our Methodology

OAG Audit provides that audit evidence for amounts recorded as costs and expenses is achieved through:

-

Assessing the risk of material misstatement for the transaction or business cycle and evaluating the design and testing the effectiveness of controls related to the costs and expense transactions (including accept‑reject and dual purpose testing for authorization, recording in proper period, and proper classification in the income statement and balance sheet).

-

Substantive audit procedures directed towards significant risks and elevated risks, including significant fraud risks.

-

Substantive audit procedures applied to balance sheet accounts (and relating or correlating amounts on the income statement with balances on the balance sheet).

-

Analytical procedures (overall conclusion analytics and, where needed, additional risk assessment analytics and/or substantive analytics).

The more pervasive risk associated with costs and expense accounts is typically the completeness of expenses recording, particularly at the end of reporting periods. Important audit procedures to address that risk are the search for unrecorded liabilities and audit procedures directed towards the adequacy of the recorded liabilities (e.g. such as, among others, workers compensation, self‑insurance, warranty). Once we are satisfied that liabilities and other balance sheet accounts are fairly stated based on the search for unrecorded liabilities, tests of estimates, tests of prepaid expenses, proper capitalization of costs, and other relevant balance sheet procedures, the primary remaining risk of misstatement to amounts recorded as expenses is related to proper classification of the underlying transactions and balances. Typically, we obtain substantive evidence on proper classification based on our testing of the accumulation of transactions into general ledger accounts and then those amounts into financial statement captions.

When we intend to leverage substantive procedures performed over a balance sheet FSLI to provide audit evidence over a related income statement FSLI (e.g., we intend to leverage substantive procedures performed over prepaid expenses to obtain some or all of the audit evidence needed to address the presentation and disclosure and accuracy assertions for the administrative expenses FSLI), and the related balance sheet FSLI is determined to be not significant (e.g., prepaid expenses are material but are determined not to be a significant FSLI), we need to consider whether the nature and extent of substantive procedures we had intended to leverage will provide sufficient evidence to respond to the risks of material misstatement identified for the applicable income statement FSLI. If we determine that further evidence is necessary, we need to plan and perform further procedures over the income statement FSLI.

We obtain evidence about the proper classification of costs by one or more of the following procedures:

-

Dual purpose control testing or accept‑reject testing designed to provide evidence that expenditures are being recorded into the proper general ledger accounts and our testing of the accumulation of costs and expenses.

-

Substantive procedures on balance sheet FSLIs provide evidence that the accounting for capitalized or deferred costs is appropriate (e.g., repair and maintenance costs versus fixed assets, capitalized interest costs, prepaid expenses, inventory costing, etc.).

-

Analytical procedures—overall conclusion analytics can help to inform us about the proper classification of balances, and they direct us to do more work when account balances (including expense account balances) don’t make sense in light of the work we have already performed. In some cases, additional risk assessment analytics (e.g., fluctuation analysis of repair and maintenance costs) or substantive analytics (e.g., analyzing the reasonableness of a particular operating expense in relation to sales) may be warranted or may already have been performed—these are also audit procedures that can be leveraged.

Occurrence and Accuracy Assertions

Most of the evidence over occurrence and accuracy assertions will come from a combination of controls and dual purpose testing in the Expenditures, Inventory Conversion and Payroll cycles; our related balance sheet testing (including testing of related estimates and accruals); and, again, analytical procedures that tell us whether balances “make sense” based on work we have performed. While the search for unrecorded liabilities test is designed to detect understatements in expenses and accruals, it also provides evidence about the existence and accuracy of accounts payable and accruals, depending on the volume and magnitude of accrued items tested. When we have additional concerns about the understatement or classification of costs and expenses, we might address those concerns with one or a combination of: 1) stronger (i.e., more precise) analytics, 2) a more extensive or deeper search for unrecorded liabilities (which might provide more “coverage” of the legitimacy of accrued liabilities), and/or 3) testing of amounts accrued that are not covered by the search (including, of course, estimates).

We do not default to using audit samples of expense items within a general ledger account or series of general ledger accounts to meet our audit objectives. In circumstances where we have concluded detailed testing of expenditures is warranted (e.g., weak internal controls, identified fraud risk, etc.), then those tests would be targeted tests, or if sampling methods are to be used, then applied to the population of related disbursements within the business process, rather than those disbursements that comprise specific income statement general ledger accounts.

Guidance below considers the application of our methodology in relation to specific categories of accounts.

Cost of Sales

Audit evidence over cost of sales is derived from the audit work already performed on inventory account balances (including costing) and audit work performed in the sales process. The cost of sales account is a residual amount derived from changes in the related balance sheet accounts—principally of inventory and the “through‑put” of the costs associated with revenue‑producing activities. In our methodology, detailed testing of cost of sales therefore tends to be limited, because we have typically already tested the balances, movements, and costing of inventory, as well as the completeness, accuracy, authorization and classification of purchases (via disbursements controls testing and the search for unrecorded liabilities and our sales and inventory cut‑off testing). These other tests provide significant audit evidence about the “residual” cost of sales balance. As a result, substantive tests of cost of sales normally can be limited to analytical procedures (risk assessment, overall conclusion and/or substantive analytics) that test the proper classification of costs and/or its overall reasonableness in relation to recorded revenues. Note that when we plan to perform substantive analytics over revenue to achieve low or moderate level of evidence and certain pre‑conditions are met, we may use thresholds that could exceed performance materiality, as explained in OAG Audit 7033.2.

An important consideration to keep in mind when thinking about cost of sales is whether we have completed sufficient audit procedures directed towards inventory costing (price testing and testing of standards). This includes not just addressing the adequacy of reserves for excess and obsolete inventory, but also price testing of materials, labor and overhead, including testing the proper classification and treatment of capitalized overhead costs, as well as the capturing of manufacturing variances and allocation of favorable / unfavorable variances to inventory

Balances Derived from the Attributes of Related Balance Sheet Accounts

It is customary to perform analytical procedures on income statement balances that are derived from the attributes of related balance sheet accounts. For example, depreciation expense is derived from accounting policies that allocate fixed asset balances to the income statement over time, and we perform analytical procedures of depreciation expense using inputs and assumptions that are reliable and predictive based on the audit work we have performed on the related fixed asset accounts. Similarly, interest expense is derived from the terms associated with related debt, and we may choose to perform analytical procedures on interest expense based on the terms of debt balances that are themselves subjected to audit procedures.

These types of accounts are conducive to substantive analytics, given their predictable nature and the reliability (due to testing) of the balance sheet‑related input data through substantive audit procedures, controls testing or a combination of both. However, substantive analytics are not always necessary. For example, one could look at interest expense as being the by‑product of information included within the Treasury cycle and instead of substantive analytics of interest expense, we might instead rely on controls we have tested over maintaining debt and its underlying terms and conditions and payments of periodic interest payments (including testing whether interest payments are being classified properly as interest expense), and test the period‑end accrued interest balance at the beginning and end of the period. Those control and dual purpose tests related to classification, together with our overall conclusion analytics, may be sufficient to achieve our audit objectives.

Balances that Represent Expenditures Adjusted by Changes in Deferrals and Accruals and Estimates

Many income statement expense items are derived from transaction cycles that involve expenditure activity adjusted by changes in accrual / deferral accounts and estimates, such as rent, commissions, property taxes, self‑insurance claims, warranty claims, etc.

For example, our client is a consumer products company that offers a manufacturer’s warranty against product defects. A “warranty claims payable” account represents claims processed and approved, but not yet paid. A “warranty IBNR reserve” represents claims estimated to be incurred but not yet reported or processed and approved. Collectively, we will refer to these as the “warranty accruals.”

Our job is to perform sufficient audit work to detect material misstatements in the accounting for warranties, if they exist. The principal audit objectives for warranty accruals would include:

-

All valid warranty claims incurred during the period are reflected in the financial statements, and all claims incurred but not yet reported or paid as of the balance sheet data are recorded as a liability.

-

Recorded warranty claims are properly measured.

-

Warranty expenses are properly classified in the financial statements.

The starting point is to understand the specifics of the company’s warranty policies as well as management’s process and related controls for capturing, validating, processing and paying warranty claims (including capturing key data, such as failure rates, incidents, costs per incident, etc.), and also for estimating incurred but not reported claims. Once we have gained that understanding, we will plan our audit strategy holistically—not separately for each of the related accounts. Since the accounting for warranty claims includes an estimate (the IBNR reserve), the holistic plan will also consider the nature and extent of evidence needed to audit that estimate.

The actual approach to auditing the warranty cycle will depend on the client circumstances, materiality and predictability, among other factors.

In one client situation we may find the relationship of warranty claims to product sold is highly predictable and controls are found to be operating effectively. Therefore we might design an audit plan and perform a substantive analytic of both warranty expenses and the warranty accruals, or perhaps a substantive analytic of warranty expense with only limited detailed testing of the related balance sheet accounts.

However, let’s assume we determine that the following approach would be used based on a client’s circumstances:

-

Obtain a balance sheet account roll forward and agree beginning and ending balances and current year expenses to the general ledger:

12/31/X1 Warranty Accruals + 20X2 Warranty Expense - 20X2 Claims Paid = 12/31/X2 Warranty Accrual -

Assess the risk of material misstatement for the cycle and evaluate the design, and test the effectiveness of controls related to the warranty transactions (including accept‑reject and dual purpose testing for classification in the balance sheet and income statement and for key inputs into the warranty calculation related to failure rates, incidents, warranty costs and units under warranty).

-

Review and test management’s process for developing the IBNR reserve.

-

Test the completeness and accuracy of the claims payable account by reviewing payments occurring after the balance sheet date or other evidence.

-

Confirm via overall conclusion analytics that the recorded account balances—warranty accrual and warranty expense—are properly classified and make sense based on the work performed.

When we are performing “control testing of warranty claims processing,” we consider incorporating dual‑purpose testing of the key attributes of each claim processed that are important to our testing of management’s process for developing the IBNR reserve. Depending on the nature of the warranty obligation and how management captures the data for formulating its assumptions, key attributes might be the product number, the date sold, the claim date, the warranty period, the nature of the incident, the claim amount submitted, the claim amount approved, and others. We may also need to incorporate testing of management’s process for accumulating and maintaining the claims data used in the assumptions (perhaps, for example, if the data is stored in a data warehouse or database separate from the transaction processing system).

In regard to warranty expense—note that in both situations no specific substantive procedures were directed to the expense balance (other than to determine that charges were properly classified), since the audit objectives for the expense balance were met by our testing of controls and/or our audit work on the balance sheet adequacy.

FAQs related to the application of—the guidance on Substantive evidence for income statement accounts other than revenue:

1. Do I need control reliance to be able to apply the above guidance?

Yes. The above guidance requires at least partial controls reliance on the transactional control objectives of occurrence and accuracy in order to apply it.

2. Can the above guidance be applied over the purchases and payable cycle when only the 3‑way match control is tested for operating effectiveness as a dual purpose test for appropriate payment and invoice approvals?

Yes. The 3-way match control generally covers off the transactional control objectives of occurrence and accuracy. It is recommended to design the control test as a dual purpose test designed to provide evidence that expenditures are being recorded into the proper general ledger accounts.

3. Should the different categories of costs and expenses be tested separately using dual purpose testing?

Generally expenses/FSLIs should be grouped for testing based on the related processes and controls. For example, it would be appropriate to group marketing expenses and general operating expenses if they are all subject to the same three way match control. However, it would be unusual for cost of sales (which would include inventory management controls) or payroll (which would include HR controls) to be included in the same population. It is expected that each of the categories of costs and expenses are tested via separate dual purpose control testing samples.

The guidance above recommends that the transactional control testing and the accept‑reject substantive test covering classification is performed as a dual purpose test because the sample sizes for controls and accept‑reject testing would be approximately the same depending on the level of evidence desired. The sample size used in the dual purpose has to be the larger of the applicable accept‑reject and the control testing sample size.

4. Can the above guidance be used for testing payroll, depreciation and interest expense?

The guidance above can be used to test payroll, depreciation and interest expense; however, it might be more effective and efficient to perform testing of these balances through analytical procedures, as these expenses are often predictive in nature.

5. Can the above guidance be applied if there is control reliance, but the engagement team was not the auditor in the prior year?

Where we were not the auditors in the prior year, it is expected that we would have reviewed the prior year's auditor working papers in order to gain comfort over the opening balances. Where we are satisfied based on this review, application of the new expense testing would be appropriate. For further information on auditing opening balances, see OAG Audit 3052.