Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

7044.1 Eight step approach to performing non-statistical audit sampling

Jun-2021

In This Section

Step 1: Determine the test objective

Step 2: Define the population and sampling unit

Step 5: Determine sample selection method

Step 6: Executing non-statistical sampling

Step 7: Assessing misstatements and projecting misstatements to the population

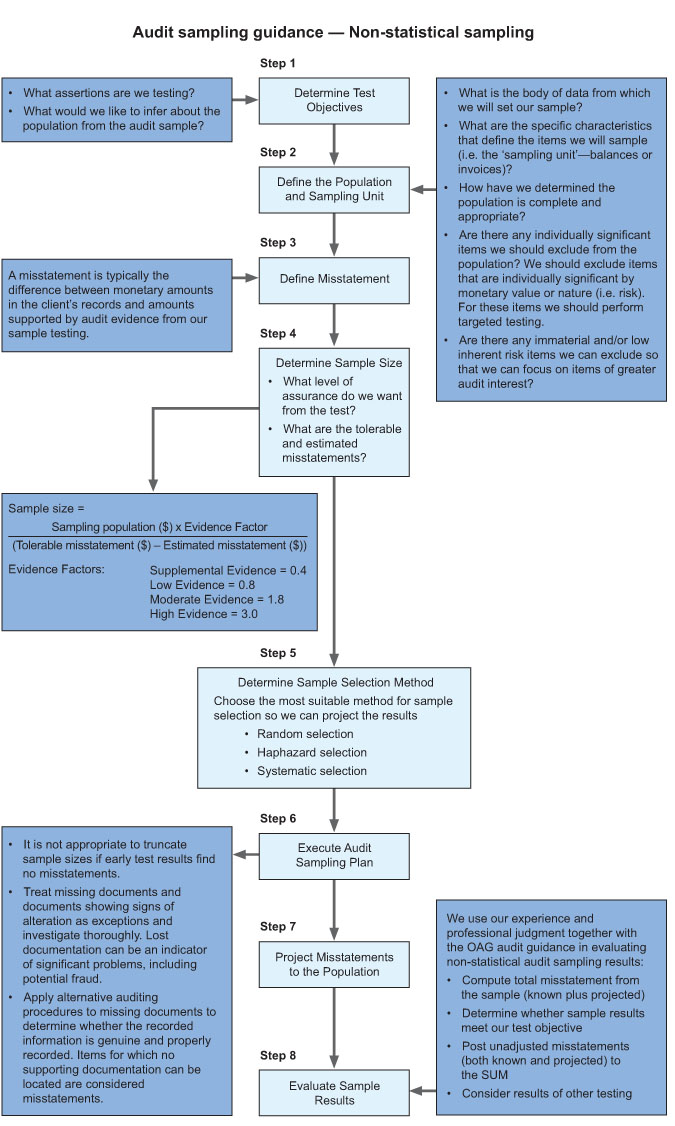

Overview

This topic explains:

-

Our eight step approach to performing non‑statistical audit sampling addressing:

- Designing an audit sampling test

- Defining the population and the sampling unit

- Defining misstatements

- Determining sample size

- Determining sample selection method

- Executing non-statistical sampling

- Assessing misstatements and projecting misstatements to the population

- Evaluating sample results

-

Practice aids for applying non-statistical sampling and documentation

OAG Guidance

The test objective is a description of what we would like to infer about the population from the sample and is related directly to the financial statement assertion we are testing (e.g., existence, accuracy). Determination of the test objective, consideration of the nature of the audit evidence sought and possible misstatements, and conditions or other characteristics relating to that audit evidence assist us in completing other steps in the sampling process (i.e., defining what constitutes a misstatement and what population to use for sampling).

A sampling plan for tests of details is generally designed to provide a particular level of evidence regarding the reasonableness of one or more assertions about a financial statement amount (e.g., the existence of accounts receivable). We carefully identify the characteristic of interest (i.e., the corroborating evidence) that is consistent with the test objective. We determine that the population from which we draw the sample is appropriate for the specific audit objective. For example, we would not be able to detect understatements of an account due to omitted items by sampling the recorded items. An appropriate sampling plan for detecting such understatements would involve selecting from a source in which appropriate evidence of any omitted items is included.

In certain circumstances when sufficient other procedures related to the relevant assertion have been performed, a Supplemental level of audit sampling may be appropriate to achieve the desired evidence from a combination of audit procedures at the assertion level.

OAG Guidance

Population

Determine that the population we intend to draw our sample from is appropriate for the specific audit objective and complete.

There is a natural tendency to designate an entire account balance or class of transactions as the population. However, the population can be restricted to the group of transactions for the time period relevant for the test and under the same system of controls that are relevant to the objectives of the test. For example, the population in a test of the valuation assertion may be restricted to past‑due receivables instead of all receivables. Similarly, if the objective is to test receivable balances remaining after targeted testing (e.g., targeted testing of large and unusual balances), then the population sampled will be accounts receivable balances remaining after targeted items have been removed.

When determining the appropriateness of the population for the planned audit procedure we consider:

-

The objective of the test (e.g., if the objective of the test is to determine whether goods delivered have been invoiced, it would be inappropriate to use recorded invoices as the sampling unit. Instead, the sampling unit would be shipping documents).

-

The direction of testing. For example, if our objective is to test for overstatement of accounts payable, the population could be defined as the accounts payable listing. Alternatively, when testing for understatement of accounts payable, the population is not the accounts payable listing but rather disbursements made subsequent to the period end, unpaid invoices, suppliers’ statements, unmatched receiving reports and/or other populations that provide audit evidence that addresses understatement of accounts payable.

We obtain audit evidence about the accuracy and completeness of information produced by the entity’s information system when that information is used in performing audit procedures. For example, if we select our sample from an accounts receivable invoice listing, we test the mathematical accuracy of the listing and reconcile the total open accounts receivable on the listing to the account balance on the general ledger.

See OAG Audit 4028.4 for further guidance on the reliability of information generated by an IT application used in our audit.

Homogeneity of populations

Generally, we define a population as the recorded amount of all items composing the account balance or class of transactions being tested. Determining a testing population involves defining the appropriate and complete set of data (e.g., transactions or balances) from which we will select our sample items and about which we wish to draw conclusions. It might be possible to combine multiple trial balance accounts as one single population if they have similar characteristics, risk factors and are subject to the same controls and systems. Professional judgment is applied in order to determine the appropriate population that is subject to a test of details taking into account factors explained in more detail below.

There may be a tendency to designate all instances of certain transactions processed centrally as a single population for our substantive testing purposes. However, when assessing the homogeneity of a substantive testing population, a homogeneous population is limited to those populations where the underlying nature of the data set is sufficiently similar and uses a sufficiently similar accounting model (e.g., all transactions in the data set follow the same revenue recognition basis, such as a single performance obligation recognized at a defined ‘point in time’ milestone). When a population is determined to be sufficiently homogeneous for substantive testing then we have concluded the characteristics are sufficiently similar to allow for conclusions to be drawn across the entire population based upon the outcome of the testing for the items included in our sample.

Careful consideration is applied when we are determining our testing populations and whether they are sufficiently homogeneous for testing. Our experience and understanding of the process(es), controls and nature of the underlying transactions, including accounting models employed, are important in determining the homogeneity of a testing population. There are a number of factors to consider and not all factors are equally important to each determination. Additionally, the evaluation of the homogeneity of populations for substantive testing is generally more complex than for control testing, because balances subject to testing may include multiple processes and/or controls and therefore we consider multiple relevant factors, whereas the evaluation of the homogeneity of a population underlying a control is performed on a control‑by‑control basis.

In making this assessment, we consider the factors described in the table below and document the overall rationale and judgment used for determining the homogeneity of the testing population. Use of the homogeneity factors and involvement by more senior members of the engagement team is encouraged when making these assessments.

Homogeneity—Factors to consider

When assessing homogeneity for substantive testing purposes there are a number of factors to consider as indicated in the table below. We assess the commonality of the processes, including the controls operating in the end‑to‑end process and their respective homogeneity when assessing the homogeneity of the related substantive testing population(s). When assessing homogeneity for substantive testing the evaluation will likely need to be performed for each individual substantive testing procedure and its underlying population.

Factors to consider when determining populations for substantive testing include

| Factor |

Homogeneity |

||

|

Not indicative < --------------------------------------------------- > Indicative |

|||

|

Commonality of the processes driving the material classes of transaction or account balance |

Unique or diverse processes |

Common or consistent processes |

|

| Factor |

Homogeneity |

||

|

Not indicative < --------------------------------------------------- > Indicative |

|||

|

Commonality of entity-level |

Different ELCs |

Some ELCs |

Same ELCs |

|

Commonality of supervisory |

Different/multiple |

Limited |

One/same supervisor |

|

Uniformity of the entity’s |

Diverse |

Similar |

Identical |

|

Number of individuals |

Larger number |

Smaller number |

|

|

Competency of the individuals executing the controls |

Varied levels of competency |

Consistent levels of |

|

|

Commonality of training |

Diverse |

Similar |

Identical |

|

Nature of the underlying |

Unique or diverse |

Identical transactions |

|

|

Whether an error identified |

An error identified would |

An error identified would be indicative of potential errors for all transactions in the population |

|

Impact of homogeneity conclusions on testing

We consider the factors above in making our determination as to whether a population is homogeneous. If the population is not determined to be homogeneous, separate populations will need to be identified and tested. If a population in its entirety is not homogenous, we could still assess if subsets of the population are homogeneous based upon the factors in the table above.

For example, an entity has designated a centralized function to process invoicing and revenue recognition for two different revenue types. One of the types is a “ship and bill” model with a single performance obligation satisfied at a point in time and the second type represents revenue for services performed that are considered a single performance obligation satisfied over time. After evaluating the factors outlined in the table above, we conclude the testing populations for certain controls executed centrally can include both revenue types, because the operation of the controls is considered to be sufficiently homogeneous. For example, the controls over customer cash collections and aged accounts receivable analyses may be the same for the two different revenue types. However, the two revenue types would not be treated as homogeneous testing populations from a substantive perspective due to significant differences in the underlying revenue contracts and accounting models. In this example, the significant difference in the nature of the underlying revenue contracts and accounting models is resulting in the conclusion to treat the two revenue types as separate populations from a substantive testing perspective.

Additional considerations—Populations containing debit and credit balances

Because the nature of the transactions resulting in debits in a given account may differ from the nature of transactions resulting in credits to the same account, the risks and relevant assertions, and therefore responsive audit considerations, may also differ. Therefore, it is necessary to consider whether it is appropriate to define a single population containing both debit and credit items together (i.e., a net population), including considering the homogeneity of the net population, or to instead consider these as separate populations. For example, an entity’s reported revenues may include both credit and debit balances. The credit balances may result from revenue recognized as a result of satisfying contractual performance obligations, whereas the debit balances might result from debit memos raised in relation to changes in variable consideration. The audit objectives and relevant assertions for testing those credit and debit balances might be different. For example, we might design a test of the accuracy and occurrence of credits to revenue (overstatement of revenues), design a separate test of the completeness of debit memos (i.e., understatement of debit memos and, consequently, overstatement of revenues), and design other tests for other relevant assertions.

If the aggregate amounts of credits and debits included in a single net population are each significant, it may be more appropriate to perform separate tests of the debit balances and the credit balances to appropriately address these differing risks and testing objectives. In that case, it would be necessary to define the debit and credit balances as separate populations for the purpose of audit sampling.

When evaluating a net population we also need to separately consider whether presenting an account balance or class of transactions on a net basis is appropriate within the context of the applicable financial reporting framework and, if not, determine if a misstatement may exist. If a misstatement is identified, we also consider whether there may be a control deficiency.

Negative/contra items within an account balance or class of transactions require careful consideration before testing all items as a single, net population. Defining a single sampling population as containing positive and negative balances may not result in a calculated sample size that reduces sampling risk to an acceptably low level. For example, when a proposed testing population contains both positive and negative items with large gross aggregate monetary values but the net monetary value of the population is small/ insignificant, the sample size calculated using the net monetary value would in most cases not provide a sufficient basis for reduce sampling risk for the population to an acceptably low level. Additionally, the evaluation of misstatements involving negative items that were included in a net population may necessitate the assistance of a statistical sampling specialist to interpret the results (e.g., projection of the differences arising from items with negative balances to the whole population). Where a testing population contains offsetting debit and credit items arising from voided items (e.g., items voided because of clerical matters such as invoices bearing incorrect mailing addresses), consider excluding the voided items (both the debits and the offsetting credits) from the sampling population after performing appropriate procedures to corroborate that the items are offsetting.

Revenue and cost of sales are most often regarded as separate classes of transactions and therefore separate populations for sampling purposes. Accordingly, it is generally inappropriate to seek reduced sample sizes by planning an audit sample to test revenue or cost of sales using a single net population defined as the gross margin. This approach may incorrectly assume that misstatements of revenue are always offset by misstatements in cost of sales or vice versa. For example, as a result of fraud, fictitious revenues may be recorded without any matching cost. As a further example, cut‑off errors might represent misstatements of either revenue or cost of sales but not necessarily both. Samples designed assuming only a gross margin population is at risk would generally be too small to provide the desired level of assurance that these and similar sources of misstatement would be detected.

Sampling Unit

Determine the sampling unit. For example, if our audit procedure is positive confirmation of receivable amounts, we select a sampling unit (such as account balance, individual unpaid invoice, or individual sales transaction) that we believe will lead to the most effective and efficient sampling application, and that is relevant to our test objective. If we select the customer account balance as the sampling unit, we test the entire customer account balance. If we do not receive a confirmation from a particular customer and that customer’s account balance is comprised of 25 invoices, when we perform alternative procedures we need to test all 25 invoices to arrive at a valid sampling conclusion. To test fewer than all 25 invoices would be “sampling a sample,” which will not permit us to arrive at a valid conclusion given the defined sampling unit. Alternatively, when designing the audit procedure we may decide that it would be more efficient to use individual unpaid invoices as the sampling unit.

We determine the total monetary value in the population and the nature of the items to be sampled. We also determine or estimate the number of items in the population (usually, we will obtain this information from the client or consider prior year experience) as different methods of determining the sample size are appropriate for smaller populations.

In addition, the source from which the sample will be selected needs to be appropriate for the test. For example, if the objective of the test is to determine whether goods delivered have been invoiced, it would be inappropriate to select the sample from a list of recorded invoices as the sampling unit. Instead, the source would be the population of shipping documents.

Exclusions from the Population

| Type of exclusion | Description |

|---|---|

|

Individually significant items |

When planning a sample, we use judgment to determine which items, if any, in an account balance or class of transactions will be individually targeted for testing rather than leaving them in the sampling population. An item may be individually significant by nature (i.e., risk) or monetary value. We select for targeted testing each item for which, in our judgment, acceptance of any sampling risk is not justified. These include (at a minimum) all individual items for which potential misstatements could exceed the amount of misstatement we can accept in the entire account or population (this amount is known as tolerable misstatement and is discussed in more detail in step 4). Any items that we target test are not part of the population from which we select an audit sample. |

|

Immaterial and/or low inherent risk items |

If we are primarily concerned with overstatements, we might identify items within a population that present relatively low inherent risk and are inconsequential in the aggregate. As a general rule, the aggregate of items to be excluded do not exceed the SUM de minimis materiality threshold. We might exclude those items from the sampling plan in order to concentrate effort on the items of greater audit interest. Removal of such items from the population to be sampled is not required. Before excluding such items, consider why there are zero balances or very small items in the population, as they may represent risk. Ordinarily, we also have prior audit experience to assess that the risk of error is ordinarily overstatement and not understatement. However, if the report being tested has zero balances as placeholders for infrequent activity (e.g., a list of all customers showing accounts receivable, even if the balance is zero), it is more appropriate to not include them in the sample. If items are to be excluded, these considerations require documentation. Analytical procedures could be applied to the low inherent risk items to the extent considered necessary. |

Related Guidance

Refer to further guidance on relevance and reliability of audit evidence at OAG Audit 1051.

CAS Guidance

The auditor’s consideration of the purpose of the audit procedure, as required by paragraph 6, includes a clear understanding of what constitutes a deviation or misstatement so that all, and only those, conditions that are relevant to the purpose of the audit procedure are included in the evaluation of deviations or projection of misstatements. For example, in a test of details relating to the existence of accounts receivable, such as confirmation, payments made by the customer before the confirmation date but received shortly after that date by the client, are not considered a misstatement. Also, a mis‑posting between customer accounts does not affect the total accounts receivable balance. Therefore, it may not be appropriate to consider this a misstatement in evaluating the sample results of this particular audit procedure, even though it may have an important effect on other areas of the audit, such as the assessment of the risk of fraud or the adequacy of the allowance for doubtful accounts (CAS 530.A6).

In considering the characteristics of a population, for tests of controls, the auditor makes an assessment of the expected rate of deviation based on the auditor’s understanding of the controls or on the examination of a small number of items from the population. This assessment is made in order to design an audit sample and to determine sample size. For example, if the expected rate of deviation is unacceptably high, the auditor will normally decide not to perform tests of controls. Similarly, for tests of details, the auditor makes an assessment of the expected misstatement in the population. If the expected misstatement is high, 100% examination or use of a large sample size may be appropriate when performing tests of details (CAS 530.A7).

OAG Guidance

A misstatement is the difference between monetary amounts in the entity’s records and amounts supported by audit evidence from our sampling application. A clear misstatement definition, prior to executing the sampling plan, is essential. Misstatement definitions need to be accurate (not too narrow or too broad) in order to result in effective sampling. For example, we would not ordinarily consider observed differences to be misstatements if they are explainable and supportable by the circumstances (e.g., timing differences for confirmations). Also, when the entity has independently identified misstatements as part of its routine system of internal controls and corrected them before we perform audit procedures on the selected sample items, these items would usually not be considered as misstatements in the sample. When we use audit sampling, generally our primary concern is overstatement.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall determine a sample size sufficient to reduce sampling risk to an acceptably low level (CAS 530.7).

CAS Guidance

The level of sampling risk that the auditor is willing to accept affects the sample size required. The lower the risk the auditor is willing to accept, the greater the sample size will need to be (CAS 530.A10).

The sample size can be determined by the application of a statistically‑based formula or through the exercise of professional judgment. Appendices 2 and 3 indicate the influences that various factors typically have on the determination of sample size. When circumstances are similar, the effect on sample size of factors such as those identified in Appendices 2 and 3 will be similar regardless of whether a statistical or non‑statistical approach is chosen (CAS 530.A11).

Examples of factors influencing sample size for tests of details (CAS 530 Appendix 3)

The following are factors that the auditor may consider when determining the sample size for tests of details. These factors, which need to be considered together, assume the auditor does not modify the approach to tests of controls or otherwise modify the nature or timing of substantive procedures in response to the assessed risks.

| Factor | Effect on sample size | |

|---|---|---|

|

An increase in the use of other substantive procedures directed at the same assertion |

Decrease |

The more the auditor is relying on other substantive procedures (tests of details or substantive analytical procedures) to reduce to an acceptable level the detection risk regarding a particular population, the less assurance the auditor will require from sampling and, therefore, the smaller the sample size can be. |

|

An increase in the auditor’s desired level of assurance that tolerable misstatement is not exceeded by actual misstatement in the population |

Increase |

The greater the level of assurance that the auditor requires that the results of the sample are in fact indicative of the actual amount of misstatement in the population, the larger the sample size needs to be. |

|

An increase in tolerable misstatement |

Decrease |

The lower the tolerable misstatement, the larger the sample size needs to be. |

|

An increase in the amount of misstatement the auditor expects to find in the population |

Increase |

The greater the amount of misstatement the auditor expects to find in the population, the larger the sample size needs to be in order to make a reasonable estimate of the actual amount of misstatement in the population. Factors relevant to the auditor’s consideration of the expected misstatement amount include the extent to which item values are determined subjectively, the results of risk assessment procedures, the results of tests of control, the results of audit procedures applied in prior periods, and the results of other substantive procedures. |

|

Stratification of the population when appropriate |

Decrease |

When there is a wide range (variability) in the monetary size of items in the population, it may be useful to stratify the population. When a population can be appropriately stratified, the aggregate of the sample sizes from the strata generally will be less than the sample size that would have been required to attain a given level of sampling risk, had one sample been drawn from the whole population. |

|

The number of sampling units in the population |

Negligible effect |

For large populations, the actual size of the population has little, if any, effect on sample size. Thus, for small populations, audit sampling is often not as efficient as alternative means of obtaining sufficient appropriate audit evidence. (However, when using monetary unit sampling, an increase in the monetary value of the population increases sample size, unless this is offset by a proportional increase in materiality for the financial statements as a whole (and, if applicable, materiality level or levels for particular classes of transactions, account balances or disclosures). |

OAG Guidance

To determine the number of items to be selected in a sample for a particular substantive test of details, we consider the tolerable misstatement and the expected misstatement, the audit risk, the characteristics of the population and the assessed risk for other substantive procedures related to the same assertion. We apply professional judgment to relate these factors in determining the appropriate sample size.

Expected misstatement (Expected error) is the total value of errors we expect to find in the population being sampled, excluding key or high value items that are evaluated separately.

The expected error is based on professional judgement, including consideration of historical experience, and assessed risk.

In order to be efficient, the expected misstatement should be less than one half the tolerable misstatement amounts. Consult Audit Services when the aggregate of the haircut and the expected misstatement for a particular sample population is greater than 50% of overall materiality.

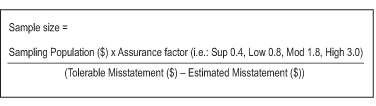

Formula to Calculate Sample Size

This formula is used for populations of 200 or more and does not include items targeted tested or items removed that are immaterial in aggregate.

When the computed sample size is not a whole number, round up to the next highest whole number.

The sample size provided by the formula is the minimum for a desired level of Supplemental, Low, Moderate or High assurance. Using a larger sample size than is suggested by the formula is permitted, but the reasons need to be documented. If larger sample sizes are deemed necessary to achieve more evidence or a more precise sampling estimate, consider using statistical sampling. For further guidance on statistical sampling, see OAG Audit 7044.2.

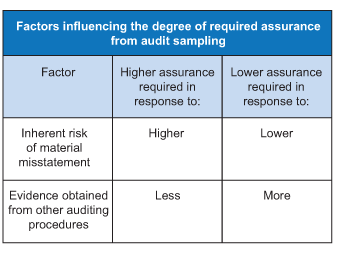

Assurance (Evidence) Factor

Determining the appropriate level of evidence at the assertion level is a matter of professional judgment and depends primarily on inherent risk and evidence obtained from other auditing procedures including tests of controls and substantive procedures.

The chart below illustrates the evidence that may be needed from audit sampling depending on the inherent risk and evidence obtained from other procedures. For example, higher evidence would be obtained from audit sampling in response to a higher inherent risk (elevated or significant) and when other auditing procedures provide less evidence.

In determining the sample size we consider whether sampling risk is reduced to an acceptably low level. In the context of audit sampling the level of assurance required and resulting sample size is inversely related to the level of sampling risk we can accept.

The greater the required evidence from audit sampling, the larger the sample size and the lower the sampling risk.

Sampling risk exists whenever we use audit sampling and arises from the possibility that our conclusions might be different from those that would have been reached if the test had been applied to all the items in the account balance or class of transactions (i.e., risk that a material misstatement could exist even though our audit sample tests provide acceptable results). While a sample might contain proportionately more or less misstatement than exists in the population, our primary concern is the risk that our sample may contain proportionately less misstatement than exists in the population. Some degree of sampling risk is always present when we sample, even when no misstatements are found in the sample items tested.

Sampling risk (the mathematical complement of which is termed confidence level) correlates to the levels of evidence in the evidence factors. While it is not possible or necessary to specifically quantify the level of sampling risk associated with non‑statistical sampling applications approximations can be used. The table below summarizes the ranges for sampling risk and the assurance factors used in the formula for each desired level of evidence:

| Desired level of assurance | Sampling risk | Confidence level | Assurance factor |

|---|---|---|---|

|

High |

7-14% |

86-93% |

3.0 |

|

Moderate |

20-27% |

73-80% |

1.8 |

|

Low |

50-55% |

45-50% |

0.8 |

|

Supplemental |

67% |

33% |

0.4 |

For example, sampling risk of 20 to 27% (moderate assurance) means that even if the sample results suggest the population is fairly stated, there is a 20 to 27% risk that the population (e.g., account balance) may be misstated by an amount in excess of tolerable misstatement.

The reason we can accept relatively high sampling risk when we need supplemental to low evidence is because when we consider inherent risk and evidence obtained from other audit procedures, relatively little assurance is needed from audit sampling to reduce the overall risk of material misstatement in a particular account or sampling population to acceptable levels.

Supplemental Level of Assurance

As stated in the table above, the Supplemental level of assurance relates to only a 33% confidence level (which corresponds to the sampling risk of 67%), and therefore will not provide sufficient substantive evidence on its own. If audit sampling is performed to obtain sufficient substantive evidence (i.e., is performed as a stand‑alone substantive test), then the Low, Moderate or High levels of assurance need to be used. Supplemental level of assurance is not to be used as the only substantive test to address the risk at the FSLI assertion level.

The Supplemental level is intended to “supplement” other substantive evidence obtained with respect to a material FSLI. Therefore, we would only use the Supplemental level of assurance when we performed sufficient other substantive procedures related to the relevant FSLI assertion.

In other words, the limited substantive evidence provided by an audit sample at the Supplemental level of assurance needs to be combined with other substantive procedures to provide the desired substantive evidence at the FSLI assertion level. As explained in OAG Audit 7011, in most cases we will design and perform one or more substantive procedures for each relevant assertion for all material classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures. When we seek to obtain substantive evidence over every relevant assertion, we need to perform other substantive tests for those assertions in addition to audit sampling at the Supplemental level. In other words, audit sampling at the Supplemental level would not be used as the only substantive test we perform for the relevant assertions. For example, when we achieved High controls reliance over the revenue FSLI and performed substantive revenue cut‑off testing, it would not be appropriate to use audit sampling at the Supplemental level as the only test to address other relevant assertions (not covered by the cut‑off testing).

We may also consider it effective and efficient to use audit sampling at the Supplemental level of assurance as part of our dual purpose testing. Sample sizes related to controls testing may be similar to the Supplemental level and therefore we may be able to achieve further efficiency by performing controls and substantive testing simultaneously to be combined with sufficient other substantive procedures.

When performing audit sampling at the Supplemental level, the estimated misstatement is zero. Zero estimated misstatement is used because if it is likely that the projected misstatement will not be zero or very close thereto when we execute the sample (i.e., if the actual misstatement observed by performing other procedures suggests likely misstatement in the population is other than trivial), the Supplemental level of assurance is not likely to provide us with the desired level of audit evidence. When considering using the Supplemental level of assurance and the estimated misstatement is not zero or very close thereto, use alternative substantive testing procedures at higher than a Supplemental level of assurance to respond to the potential risk.

Because we only use the Supplemental level of assurance when we have performed sufficient other procedures related to the relevant assertion, we normally have information about the actual misstatement in the population. When clearly trivial misstatements have been identified as a result of other procedures (e.g., targeted testing) performed prior to applying audit sampling at the Supplemental level, we may still perform the Supplemental testing using zero as the estimated misstatement as long as the likely population misstatement suggested by other procedures is sufficiently small (not expected to exceed the de minimis SUM posting level) and we appropriately consider the potential increased risk associated with the misstatements observed.

We consider targeted testing, either on individually significant transactions or risk based before performing sampling tests at any level.

Example

The Supplemental level could be used to supplement other substantive evidence to reduce the audit risk to a sufficiently low level on relevant assertions (e.g., occurrence and accuracy throughout the period) for revenue. When testing revenues and we have achieved High controls reliance over the Revenue FSLI, obtained substantive evidence regarding the accounts receivable balance, including cut‑off and accounts receivable testing at the beginning and end of the year, performed risk based targeted testing of revenue transactions and journal entry testing, but have not obtained sufficient evidence from such substantive procedures, then testing at the Supplemental level may be performed to provide sufficient evidence. The Supplemental level does not change our fundamental approach to testing revenue and it is not intended to replace other substantive testing between the period ends, such as targeted testing, journal entry testing or revenue substantive analytical procedures but rather supplement those other evidence gathering activities.

Impact of Tolerable Misstatement on Sample Size

Once we have determined the level of evidence required, determining the appropriate sample size is based on excess of tolerable misstatement over estimated misstatement. The smaller the difference between tolerable and estimated misstatement the more precise the necessary sample conclusion and therefore the larger the necessary sample size.

Important points to consider with regard to tolerable misstatement:

-

It is the largest amount of misstatement we can tolerate in an account or population and still conclude we have obtained sufficient assurance that the account does not contain a material misstatement.

-

It does not exceed performance materiality.

-

Generally it is equal to performance materiality. However, it may be set below performance materiality where a more precise test is required in response to account‑level qualitative factors such as the effect of material misstatement on debt covenants, important trends and ratios. This also applies to balance sheet accounts rather than another balance sheet driven amount (e.g., 5% of total assets) since an error in balance sheet accounts will ordinarily also impact the income statement. Performing non‑statistical sampling on companies with large asset or liability balances in relation to performance materiality frequently results in large sample sizes therefore consideration is needed as to whether other audit procedures would give a more efficient outcome.

-

Where we determined materiality for particular classes of transactions, account balances or disclosures, we take those levels into account when determining tolerable misstatement. The tolerable misstatement for such accounts would ordinarily be equal to related specific materiality level.

-

It is larger than the estimated misstatement.

-

It almost always exceeds the SUM de minimis threshold level (because the de minimis amount is a matter of convenience in posting items to the SUM rather than the amount of misstatement considered material for a particular account).

-

If it is set too low it may result in a large sample size and may not be an efficient test.

-

It is subjective, like overall materiality, and may change during the course of the engagement.

-

When a FSLI is comprised of multiple trial balance accounts which are all subject to non‑statistical sampling, performance materiality does not necessarily need to be disaggregated to each trial balance account in establishing the tolerable misstatement and determining the appropriate sample sizes under non‑statistical sampling. However, additional consideration is required when not all account balances or classes of transactions included within the FSLI are subject to substantive audit procedures. In these situations, we apply a tolerable misstatement amount lower than performance materiality to each trial balance account subject to non‑statistical sampling in order to reduce aggregation risk. Consider the example below:

Performance materiality is $100k, and the class of transaction (i.e. Revenue) is recorded as four trial balance accounts amounting to a total of $1m:- Account 1 - $250k

- Account 2 - $500k

- Account 3 - $200k

- Account 4 - $50k

In this scenario, if we decide to perform non‑statistical sampling for all four account balances, we would normally use performance materiality for each account as the tolerable misstatement for determining the non‑statistical sample size.

Alternatively, if test of details are not planned for account 4 because it is individually below performance materiality and non‑statistical sampling is the only procedure used in testing the remaining balance of accounts 1 to 3, then tolerable misstatement is set at an amount that is lower than performance materiality for each tested balance to address the aggregation risk presented in the balance that was not subject to testing.

If tolerable misstatement is > 20% of the overall account balance or sampling population, carefully consider whether sampling is the appropriate testing application, because, for instance, it can mean that 20% of the account or population would need to be incorrect to have a material misstatement. In these circumstances, it may be more efficient to test by relying on controls, substantive analytical procedures, targeted testing or some combination of these.

Impact of Estimated Misstatement on Sample Size

We assess the estimated misstatement on the basis of professional judgment after considering such factors as the entity’s environment and risks, the results of prior years’ tests of the account and the results of other tests applied in the current period such as targeted testing, substantive analytical procedures and tests of controls. Estimated misstatement is a critical component in the evaluation of our sample results and therefore a reasonable estimate of expected misstatement is necessary.

If we select a sample size based on an estimated misstatement that turns out to be inappropriately low as the actual sample results yield a higher amount of total misstatement, then results may not be acceptable to achieve the desired level of assurance (i.e., the test could be deemed to be invalid and additional testing may be necessary). Conversely, if our estimated misstatement is unnecessarily high, we will test a larger sample than is needed to attain our desired level of assurance. See step 8 below for further guidance on evaluation of results and consideration of sampling risk.

As previously noted under the heading Supplemental level of assurance, when performing audit sampling at the Supplemental level, the estimated misstatement is zero. When considering using the Supplemental level of assurance and the estimated misstatement is not zero or very close thereto, use alternative substantive testing procedures at higher than a Supplemental level of assurance to respond to the potential risk.

Relationship Between Tolerable Misstatement and Estimated Misstatement

The excess of tolerable misstatement over estimated misstatement is a measure of how precise the conclusions from our sampling application will be. It is the key factor to consider when deciding on the appropriate sample size for a particular level of evidence (see sample formula above). The importance of the excess of tolerable misstatement over estimated misstatement in determining sample size is related to the uncertainty caused by examining less than 100% of a population (sampling risk or the risk that our sample may contain proportionately fewer misstatements than actually exist in the population). The narrower the range between tolerable misstatement and estimated misstatement, the more precise our estimate of the population misstatement resulting from our sample needs to be. Larger sample sizes yield more precise estimates (reduced sampling risk or margin for uncertainty).

Audit sampling is not the appropriate audit approach if estimated misstatement is greater than tolerable misstatement or even if it is very close to it (i.e. estimated misstatement > 70% of tolerable misstatement) or if we estimate that the population has a high misstatement rate (i.e. > 5%). In these cases reconsider the testing strategy, including whether sampling is necessary to obtain sufficient evidence.

It is recommended to have management review and correct the expected errors in the population so that, if sampling is still considered the appropriate strategy, the estimate of tolerable misstatement will be less. If it is not possible to have the client correct the data and sampling is the only option, we may be able to use statistical sampling rather than non‑statistical sampling approach. In such cases, consult with the Internal Specialist of Research and Quantitative Analysis. For further guidance on statistical sampling, see OAG Audit 7044.2.

The impact of targeted testing on tolerable and estimated misstatement and sample size

In the relatively small number of cases when targeted testing and audit sampling are conducted at the same time, tolerable and estimated misstatement are determined based on the overall account basis. The expected misstatement rate is applied to the sampling population to determine estimated misstatement used in the sample size formula. In most cases targeted testing will be completed before we apply audit sampling; in these cases we might still determine tolerable and estimated misstatement on the overall account basis, but more often we use the results of the targeted testing to adjust tolerable misstatement and to inform our judgment of estimated misstatement.

Before we apply audit sampling, consider increasing the portion of the account that is targeted tested, as increasing targeted testing will potentially reduce the sample size. At a minimum, we select for targeted testing all individual items whose monetary value exceeds the amount of tolerable misstatement.

Audit Sampling Performed at an Interim Date

We may decide to perform audit sampling on a population of transactions through an interim date. Strategies for the remainder of audit work to be completed when audit sampling is performed as of an interim date include:

-

Performing appropriate testing procedures (other than audit sampling) for the remaining period in accordance with OAG Audit 7015. These procedures would include substantive procedures combined with tests of controls or substantive procedures only.

-

Performing audit sampling for the remaining period, if it is determined that audit sampling is the appropriate test of details. In this case we may only need a low or supplemental level of assurance from the audit sample based upon facts and circumstances, including successful interim testing and other testing performed. Note that sampling results can only be projected to the population from which it was selected (i.e. interim and remaining period populations need to be treated as separate complete populations). Therefore, extrapolating results from the interim population to that at year end is not appropriate.

-

Designing an audit sample to cover the full year population. Determine the sample size based on an estimate of the total population for the year. Allocate a portion of the sample to interim period transactions that is representative of the interim period transactions and complete that portion at an interim date. Once the final population amount is known at year end, recalculate the sample size for the full year and sample the remaining number of items necessary to complete the full year sample. Identified misstatements will be projected over the full year population.

Note that if separate samples are taken for interim and the remaining period, the combined sample size would normally approximate the sample size of a sample of the full year population. One possible benefit of performing a separate interim and year end sample is that if misstatements are noted, they would only be projected over their respective populations and not the full year population.

Population of < 200 Items

If a population contains fewer than 200 items, we may want to reconsider the decision to use audit sampling. When a population is very small, other auditing procedures (e.g., targeted testing) may be more effective and more efficient than audit sampling. If it is still concluded that non‑statistical sampling is appropriate in the circumstances and a population contains fewer than 200 items, we can use a sample size smaller than those provided by the formula. A percentage of the sample size provided by the formula can be applied as follows:

| Population size | % of sample size provide by formula |

|---|---|

|

175 |

85% |

|

100 |

70% |

|

60 or less |

55% |

Interpolation of these percentages is permitted. The automated non‑statistical sampling template performs this computation automatically.

Practice Aid

The Non-Statistical Sampling Test template within Test of Details template Menu is recommended to assist teams in calculating an appropriate sample size. However, when designing Supplemental level sampling, auditors should use IDEA to calculate the sample size (confidence level of 33% and estimated error of zero).

Related Guidance

OAG Audit 7011 explains the relationship between the amount of evidence obtained from controls and the evidence required from our collective substantive testing.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall select items for the sample in such a way that each sampling unit in the population has a chance of selection (CAS 530.8).

CAS Guidance

With statistical sampling, sample items are selected in a way that each sampling unit has a known probability of being selected. With non‑statistical sampling, judgment is used to select sample items. Because the purpose of sampling is to provide a reasonable basis for the auditor to draw conclusions about the population from which the sample is selected, it is important that the auditor selects a representative sample, so that bias is avoided, by choosing sample items which have characteristics typical of the population (CAS 530.A12).

The principal methods of selecting samples are the use of random selection, systematic selection and haphazard selection (CAS 530.A13).

OAG Guidance

Random Selection

Random selection method allows for all items in the population to have an equal chance of being selected. To apply the random selection method, we can use random number tables, random numbers generators or random selection offered by sampling software such as Microsoft Excel and IDEA.

Haphazard Selection

Haphazard selection method provides for selecting a judgmentally representative sample without relying on a truly random process or on a structured technique. “Haphazard” does not mean without thought or effort. Sample items are selected without any conscious bias, (i.e., without any special reason for including or omitting items from the sample) or predictable pattern because to do so would not provide an equal chance for selection of all items in the population we are testing. For example it would not be appropriate to:

-

Select revenue transactions solely related to one or very few customers when an entity has many customers. For example, when the population is comprised of daily transaction batches but our sampling unit is individual revenue transactions, we would select transactions from batches throughout the period (but it is not generally expected that each entry will be from a separate batch).

-

Avoid selecting items because we believe it will be difficult for management to provide supporting documentation.

-

Always choose or avoid items based on a pattern such as the first or last entries on a page.

When random selection methods can be applied efficiently, they are preferable because they exclude potential bias. However, haphazard selection may be an acceptable alternative to random selection when electronic data is not readily available and if we are confident selection conditions will not introduce bias, the selection is representative of the population and each item in the population has a chance to be selected. Haphazard selection is not appropriate when using statistical sampling.

Systematic Selection

Systematic selection method selects every nth item (sampling interval) regardless of size or monetary value. For example, if there were 600 trade receivables and we wished to select 20 balances, we might select every thirtieth balance. To use systematic selection we haphazardly or randomly select the first sample item from the first interval of 1–30 items and then select every thirtieth item. In this example, if the first item haphazardly selected was 13, the next item would be 43, then 73, and so on. Microsoft Excel can perform systematic selection (in Excel, go to the Tools menu, then Data Analysis and then Sampling).

Systematic selection is not appropriate when the characteristics are not distributed randomly throughout a population. An example of a population that is not randomly ordered is a payroll record for a construction company where the payroll register is organized by teams; each team consists of a crew leader and nine other workers. In this circumstance, a selection of every tenth employee would either include all or no crew leaders, depending on the random start.

Stratification

Stratification is the process of dividing a population into subpopulations or stratum, each of which is a group of sampling units which have similar characteristics (e.g., values within a monetary range or similar risk attributes). Each stratum is examined separately. In this way, items with similar characteristics are included in each subpopulation (stratum). Separating populations may reduce the variability of items in each stratum, which may provide two potential benefits (1) stratification provides greater precision in the test outcome because observed errors are projected only to the stratum where the test differences were identified; and (2) stratification allows the sample size to be reduced without a proportional increase in sampling risk. Subpopulations need to be carefully defined such that any sampling unit can only belong to one stratum.

However, if the variability within strata is not reduced, relative to the overall variability in the population, no benefit is gained. Any anticipated reduction in sample size would then have to be compensated by additional audit work.

Our non-statistical sampling methodology assumes no stratification and compensation for not considering stratification is embedded in the sampling formula. As such, we are not required to perform stratification. However, in circumstances where we consider it effective and efficient, we may perform stratification of the population, in which case, if the stratification approach reduces monetary variability of items within the strata when compared to the variability of items in the entire population, we can adjust the sample size produced by the formula (i.e., by reducing the resulting sample size by a factor of 10%). Therefore, when stratifying by risk, if the risk does not reduce monetary variability, it would not result in a reduced sample size. Further details and examples are provided below.

When a population is stratified, misstatements identified as part of the test are projected separately for each stratum. Projected misstatements for each stratum are then added together to form an aggregated projected misstatement for the total population in line with the existing thresholds in Step 8: Evaluation of sample results.

Stratification—Monetary Value

Monetary stratification means dividing a population into two or more distinct subpopulations by monetary value (normally two strata). This approach allows us to focus relatively more testing on large monetary items. Normally the two strata are equal in size in terms of total monetary value and the computed sample size is allocated equally across the two strata. However, if the identified strata have unequal monetary values (e.g., a large pool of relatively small transactions makes up 1/3 of the monetary value of the population and the remaining 2/3 of the population is made up of larger items the sample size is allocated proportionately.

Stratification—Risk

A population may also be stratified according to a particular characteristic that indicates a higher risk of misstatement. For example, when testing the allowance for doubtful accounts in accounts receivable, balances may be stratified into several strata by age of the receivables. Before stratifying by risk, we first consider whether the risk characteristics identified:

-

may instead provide an effective and efficient basis for performing risk‑based targeted testing, or

-

may be an indication that we have not appropriately identified a homogeneous sampling population in accordance with Step 2: Define the population and sampling unit.

When stratifying by risk, the computed sample size for the population is allocated to the individual stratum proportionately based on their monetary values relative to total population monetary value. Unlike monetary stratification, where the expected errors needs to be the same for each stratum, when performing stratification by risk we can compute sample size using different expected error for each stratum.

Additional guidance on sample selection method

To further clarify, with non-statistical sampling, all transactions have an equal opportunity of being selected. When selecting samples from batches, some level of combining may be acceptable such as selecting 2–4 samples from each batch. However, we would generally expect no more than 4 samples should be selected from one batch.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall perform audit procedures, appropriate to the purpose, on each item selected (CAS 530.9).

If the audit procedure is not applicable to the selected item, the auditor shall perform the procedure on a replacement item (CAS 530.10).

If the auditor is unable to apply the designed audit procedures, or suitable alternative procedures, to a selected item, the auditor shall treat that item as a deviation from the prescribed control, in the case of tests of controls, or a misstatement, in the case of tests of details (CAS 530.11).

CAS Guidance

An example of when it is necessary to perform the procedure on a replacement item is when a voided cheque is selected while testing for evidence of payment authorization. If the auditor is satisfied that the cheque has been properly voided such that it does not constitute a deviation, an appropriately chosen replacement is examined (CAS 530.A14).

An example of when the auditor is unable to apply the designed audit procedures to a selected item is when documentation relating to that item has been lost (CAS 530.A15).

An example of a suitable alternative procedure might be the examination of subsequent cash receipts together with evidence of their source and the items they are intended to settle when no reply has been received in response to a positive confirmation request (CAS 530.A16).

OAG Guidance

In executing our non-statistical sample, we examine evidence, appropriate to meet the purpose of the test, for each item selected. We may find that an item initially selected for testing is not appropriate, or the required evidence cannot be found. Our response in such circumstances is outlined below:

Voided Items

Occasionally, a random sample includes an item that has been voided. In determining that an item has been properly voided we obtain evidence that the underlying explanation for voiding the item is appropriate, normally by determining that authorized personnel voided the item for a legitimate business purpose. Voided items that do not result in a subsequent adjustment to the recorded amount are not generally counted as misstatements. For example, items that are voided because of clerical misstatements (e.g., invoices bearing incorrect mailing addresses) and replaced by correct items have no impact on the recorded amounts and are not considered misstatements. Once we are satisfied as to the propriety of the voiding procedure, we would ordinarily select another item to replace the voided sample item. If the voided item did require an adjustment to the recorded amount and the client properly followed the voiding procedure and made the proper adjustment, then there is no misstatement. In this case, an audited amount can be determined and the sample item included in the population.

If voiding of the selected item resulted in an adjustment to the recorded amount being required but the adjustment was not recorded or was recorded in a subsequent accounting period, then the item is to be counted as a misstatement. Assume, for example, that we selected a sample of unpaid customer invoices for confirmation. An invoice that was outstanding as of the confirmation date, and subsequently voided because the original billing was misstated, represents a misstatement in the accounts receivable balance at the confirmation date.

Unlocatable Documents

Unlocatable documents include requests for confirmation of information to which third parties do not respond or specified documents that cannot be located in the clients files. In these circumstances, an alternative auditing procedure needs to be applied to determine whether the recorded information is genuine and properly recorded. Items for which supporting documentation cannot be located, and thus cannot be audited, are considered misstatements regardless of monetary value and are treated as known misstatements in the sampling calculations (i.e., included in the calculation of the misstatement rate for projecting misstatement to the untested portion of the population as well as included with other known misstatements and, if above the de minimis level, posted to the SUM). Thoroughly investigate missing documentation because, while it may represent an inadvertent misplacement of documents, it can also be an indicator of serious issues, including potential fraud. Depending on the circumstances, it may be appropriate to consult with the engagement leader or team manager if the client has lost or destroyed documentation.

Unused Items

Occasionally, a sample includes an item that has not been used. For example, customer account numbers may not be assigned in consecutive numerical sequence. If the item selected for testing was not used, we verify the item has not been used (i.e., it is not a voided or unlocatable item) and replace the unused item with another item.

Thoroughly investigate any documents showing sign of alteration as they can be a significant indicator of problems including potential fraud.

Impact of Early Test Results

It is not appropriate to reduce sample sizes if the results of the audit test applied to the first selected items indicate no misstatements. For example, if after testing the first 10 items from a sample of 20, no misstatements are detected, it is not correct to conclude the remaining 10 items need not be tested. The reduced sample would not provide the level of evidence previously deemed necessary. On the other hand, it may be appropriate to halt testing if the results of the audit test applied to the first selected items indicate significant misstatements that, when projected, suggest the population is materially misstated. If audit sampling is halted due to the number and size of those misstatements we find, it may be necessary for the client to identify the source of the misstatements and correct the population. We then retest using audit sampling or other audit procedures. If we retest using audit sampling, we generally increase our sample size to gain sufficient evidence the source of the misstatements originally identified has been corrected.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall investigate the nature and cause of any deviations or misstatements identified, and evaluate their possible effect on the purpose of the audit procedure and on other areas of the audit (CAS 530.12).

In the extremely rare circumstances when the auditor considers a misstatement or deviation discovered in a sample to be an anomaly, the auditor shall obtain a high degree of certainty that such misstatement or deviation is not representative of the population. The auditor shall obtain this degree of certainty by performing additional audit procedures to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence that the misstatement or deviation does not affect the remainder of the population (CAS 530.13).

For tests of details, the auditor shall project misstatements found in the sample to the population (CAS 530.14).

CAS Guidance

In analyzing the deviations and misstatements identified, the auditor may observe that many have a common feature, for example, type of transaction, location, product line or period of time. In such circumstances, the auditor may decide to identify all items in the population that possess the common feature, and extend audit procedures to those items. In addition, such deviations or misstatements may be intentional, and may indicate the possibility of fraud (CAS 530.A17).

The auditor is required to project misstatements for the population to obtain a broad view of the scale of misstatement but this projection may not be sufficient to determine an amount to be recorded (CAS 530.A18).

When a misstatement has been established as an anomaly, it may be excluded when projecting misstatements to the population. However, the effect of any such misstatement, if uncorrected, still needs to be considered in addition to the projection of the non-anomalous misstatements (CAS 530.A19).

OAG Guidance

Understanding Misstatements

The understanding of misstatements uncovered during sampling is an integral part of the testing and review process and requires documentation. In addition to the evaluation of the frequency and amounts of monetary misstatements, consideration of the qualitative aspects of the misstatements is required. These include:

-

The nature and cause of misstatements, such as whether they are differences in principle or in application, are errors or are caused by fraud, or are due to misunderstanding of instructions or to carelessness.

-

The possible relationship of the misstatements to other phases of the audit. The discovery of fraud ordinarily requires a broader consideration of possible implications than does the discovery of an error. We also relate the evaluation of the sample to other relevant audit evidence when forming a conclusion about the related account balance or class of transactions.

If there is evidence that suggests a misstatement may be considered an anomaly consult with the team manager and potentially the engagement leader. Clearly document the basis for and evidence to support the conclusion reached.

If the nature and frequency of misstatements suggest that assumptions made earlier in the audit were not appropriate, we reconsider the initial audit approach. For example, a large number of misstatements discovered in the confirmation of receivables might indicate the need to reconsider our planned controls reliance related to the revenue and receivables business process. If any misstatements indicate possible fraudulent activities, report the findings to the engagement leader and carefully consider and document possible audit implications of the finding.

Regardless of our conclusions as to the need to revise the audit plan in response to detected misstatements, we document our conclusions and advise the client of our findings so they can take corrective action.

Projecting Misstatements (Most Likely Error)

The purpose of audit sampling is to draw inferences from the sample to the population. We project the misstatement results of the sample to the sampling population from which the sample was selected.

The projected misstatement amounts are differences considered likely to exist based on extrapolation from audit evidence obtained. Known audit differences identified during the sampling process are projected to the total population being tested. Because conclusions based on sample results apply only to the population from which the sample items were selected, the population must have been carefully defined (see step 2). There are a number of acceptable methods of projecting errors identified in the sample to the population; however, the OAG preferred approach is to use IDEA.

When using non-statistical sampling, we use IDEA to calculate the most likely error to determine the total misstatement amount (projected misstatement amount plus the known audit differences) for the population.

Sampling at a Supplemental level of assurance may allow a sample to meet the test objective even if the total sample misstatement is above estimated misstatement so long as the total sample error is no more than the de minimis SUM posting level. When we observe more misstatement than expected, the test yields slightly lower confidence level than we had planned and it is important for us to appropriately consider the potential increased risk associated with the misstatements observed as well as the slightly lower confidence. Even low levels of misstatement identified as a result of sampling at the Supplemental level may indicate inconsistencies with the information we have already obtained from other procedures regarding the likely population misstatement. If, based on our understanding of the errors found, the risk and confidence are acceptable, we may conclude the test objective has been met. When the total sample misstatement is more than zero and less than the de minimis SUM posting level and we conclude the test has not met our objective, we perform additional substantive procedures such as targeted testing, substantive analytics, or audit sampling at assurance levels higher than Supplemental. Also, if the total sample misstatement exceeds the de minimis SUM posting level, we need to perform additional substantive procedures at assurance levels higher than the Supplemental level of assurance. Our judgments on the evaluation of projected misstatements and conclusions need to be documented in the workpapers.

Isolation and Containment

When misstatements are identified and investigated, they commonly are found to have some “unusual” or “unique” quality or characteristic. There is a natural tendency to want to isolate misstatements that are “unique” and not project the items to the population (particularly when the resulting misstatement projection is unacceptably high). However, the isolation of misstatements is not appropriate. The purpose of audit sampling is to draw inferences about the entire population by examining only some items. While some misstatements may appear “unique,” they may be representative of other “unique” misstatements in the population. The problem with isolation is that we can rarely conclude that the remaining population contains no more “unique” items.

If the misstatement projection from audit sampling is unacceptably high, and if client adjustments do not reduce risk to an acceptable level, there might be instances when a form of misstatement “containment” is a practical solution. This means that we consider whether information obtained about some misstatements identified by audit sampling can justify the creation of a new subpopulation to be tested separately. This new subpopulation would be made up of items with characteristics similar to the sample items with misstatements we would like to “contain” so that we can conduct additional focused testing on the area most likely to contain similar misstatements.

As an example, in testing accounts receivable, one rather large misstatement is discovered in an international customer balance. The misstatement was caused by the client’s incorrect foreign currency translation computation, and further investigation reveals there were only 15 sales to foreign customers during the year. In this case, we may be justified in applying targeted testing to these 15 items and removing them from the evaluation of the population sampled.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall evaluate (CAS 530.15):

(a) The results of the sample; and

(b) Whether the use of audit sampling has provided a reasonable basis for conclusions about the population that has been tested.

CAS Guidance

For tests of controls, an unexpectedly high sample deviation rate may lead to an increase in the assessed risk of material misstatement, unless further audit evidence substantiating the initial assessment is obtained. For tests of details, an unexpectedly high misstatement amount in a sample may cause the auditor to believe that a class of transactions or account balance is materially misstated, in the absence of further audit evidence that no material misstatement exists (CAS 530.A21).

In the case of tests of details, the projected misstatement plus anomalous misstatement, if any, is the auditor’s best estimate of misstatement in the population. When the projected misstatement plus anomalous misstatement, if any, exceeds tolerable misstatement, the sample does not provide a reasonable basis for conclusions about the population that has been tested. The closer the projected misstatement plus anomalous misstatement is to tolerable misstatement, the more likely that actual misstatement in the population may exceed tolerable misstatement. Also if the projected misstatement is greater than the auditor’s expectations of misstatement used to determine the sample size, the auditor may conclude that there is an unacceptable sampling risk that the actual misstatement in the population exceeds the tolerable misstatement. Considering the results of other audit procedures helps the auditor to assess the risk that actual misstatement in the population exceeds tolerable misstatement, and the risk may be reduced if additional audit evidence is obtained (CAS 530.A22).

If the auditor concludes that audit sampling has not provided a reasonable basis for conclusions about the population that has been tested, the auditor may (CAS 530.A23):

-

request management to investigate misstatements that have been identified and the potential for further misstatements and to make any necessary adjustments; or

-

tailor the nature, timing and extent of those further audit procedures to best achieve the required assurance. For example, in the case of tests of controls, the auditor might extend the sample size, test an alternative control or modify related substantive procedures.

OAG Guidance

In evaluating non-statistical sampling results, we use experience and professional judgment and consider the guidelines provided below. In any evaluation of sample results larger sample sizes result in more accurate estimates of the actual population misstatement.

The results of our procedures need to be evaluated before we can reach a final conclusion about the non‑statistical sampling procedure. We also consider the impact on other areas of the audit. Even if the total misstatement from the sample is less than tolerable misstatement, we still need to appropriately consider sampling risk or the risk that our sampling results might underestimate the actual misstatement in the population tested. The original sample size may have been calculated using an inappropriately low estimated misstatement resulting in an original sample that was too small to achieve the desired level of evidence. An allowance for sampling risk is built into the sample size in the denominator of the sample size formula and is the difference between tolerable and estimated misstatement. Therefore, we evaluate whether the sample size is sufficient to achieve our desired level of evidence by comparing total misstatement resulting from the sample with the estimated misstatement used to determine the original sample size.

If our total misstatement from the sample is less than or close to the estimated misstatement we used to calculate the sample size, we have sufficient evidence at the planned level of evidence that the sampling population does not contain a misstatement greater than tolerable misstatement.

Consideration of Sampling Risk When Total Misstatement Is Greater Than Estimated Misstatement

If total misstatement is greater than estimated misstatement, we still may be able to conclude based on judgment that the sample results have met our test objective, however at a slightly lower confidence level than we had planned. Under these circumstances, document our judgments and conclusions.

We, use the following rules of thumb in our evaluation of the sample results:

| Outcome condition | Outcome |

|---|---|

|

Outcome condition 1 |

Total misstatement from the sample < or = estimated misstatement. This outcome condition indicates that we have met our test objectives or that we have obtained sufficient appropriate evidence that the sampling population does not contain a misstatement greater than tolerable misstatement at our planned level of desired evidence. |

|

Outcome condition 2 |

Total misstatement from the sample > estimated misstatement. This outcome condition suggests that we have not met our planned test objective and that the sample size may have been insufficient. The larger the total misstatement, the higher the risk that the sampling population contains a misstatement greater than tolerable misstatement. We may be able to use the evidence provided by the non‑statistical sample if, in our professional judgment, we are able to accept a lower level of evidence from the test. This decision will depend upon the results of other sources of assurance for the particular FSLI as well as the results for other FSLI within the financial statements as a whole. Document the rationale and support for that conclusion. |

|

Outcome condition 3 |

Total misstatement from the sample > tolerable misstatement. This outcome condition indicates an unacceptably high likelihood that the account is materially misstated. Additional testing by the team and/or client is likely warranted. |