Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

4028.3 ITGC testing

Sep-2022

In This Section

OAG Guidance

As described within OAG Audit 5035.2, the ITGC testing approach is based upon the understanding of the IT applications and the relevant IT dependencies. This will include consideration of the type of application, the IT risks relevant to the IT dependencies and controls addressing those risks.

The evidence needed to confirm whether an ITGC is operating effectively depends on the risk associated with the ITGC. While many are pervasive (i.e., numerous automated information processing controls across multiple processes may depend on them), pervasiveness, by itself, does not automatically dictate the nature in which we test them. Rather, pervasiveness is one of several risk factors that need to be considered. The type of testing procedure performed is determined based on the risk factors considered. Avoid defaulting to reperformance tests for all ITGCs. See OAG Audit 6053 for further guidance on the extent of testing controls. Also, when determining to what extent we can use the work of internal auditors with respect to ITGCs, it is important to consider that we can place greater reliance on the work of internal auditors for ITGCs that are not higher risk. For example, we may use internal audit to test controls over backups of data, controls that typically involve less judgment but would be less likely to use them to test a change control that considers whether procedures are planned and executed in a manner that is sufficient and appropriate to the nature of the change and its associated risks. See OAG Audit 6030 for further guidance on considerations when using the work of internal audit or equivalent function. Additionally, note that regular control testing rotation as mentioned in CAS 330.14, normally does not apply for ITGCs and we normally need to test at least some ITGCs in the current audit. Refer to OAG Audit 6056 for further guidance on how CAS 330.14 impacts ITGCs.

A “one size fits all” approach to testing ITGCs does not address the risks that are relevant to the audit in an effective and efficient manner. When developing an ITGC testing approach it is important to note ITGC domains and ITGCs within them may have varying degrees of relevance to the audit. It is important to appropriately identify the IT dependencies relevant to the audit and assess the IT risks during the planning phase of the audit through collaboration with IT Audit, where applicable. The testing approach would then be tailored to address the associated risks and provide sufficient evidence to rely upon the continuing operation of the relevant IT dependencies.

Further guidance in relation to understanding the relevant ITGC domains (Access to programs and data, Program change, Program development and Computer operations) is included in OAG Audit 5035.2.

OAG Guidance

Introduction

By the nature of IT operations, written evidence about the operation of ITGCs may not always be readily available or consistently maintained, but the controls may still be effective, we just have to find appropriate, if different, evidence. ITGC deficiencies need to be evaluated for their individual and collective impact on the reliability of information processing controls and other system generated information (i.e., reports) prior to making judgments that would suggest significant changes to the audit strategy. When our past audits have indicated that the IT control environment is deficient or certain ITGCs are ineffective and we know there has been insufficient remediation of such controls, our audit plan needs to be developed in consideration of the potential inability to rely on any impacted IT dependencies for the financial statement audit. Typically, it would be necessary to obtain only limited evidence to confirm that ITGCs with un‑remediated deficiencies remain ineffective. However, it is important that if the integrity of an IT dependency is impacted by one or more ITGC deficiencies, we do not default automatically to the assumption that the IT dependencies cannot be relied upon and perform additional substantive testing of account balances and transactions. Use professional judgment to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the ITGCs in providing evidence of the integrity of the IT dependencies that depend on them during the period of time over which the ITGCs have been evaluated. Determine whether the ITGC deficiency culminated in compromising the integrity of the IT dependency. If we determine that the ITGC deficiency or combined deficiencies impacts one or more IT dependencies, consider applying an alternative testing approach to these IT dependencies before revising the audit plan to reflect the lack of controls reliance. Refer to OAG Audit 6054 and OAG Audit 4028.4 for guidance on how to test IT dependencies when ITGCs have not been tested.

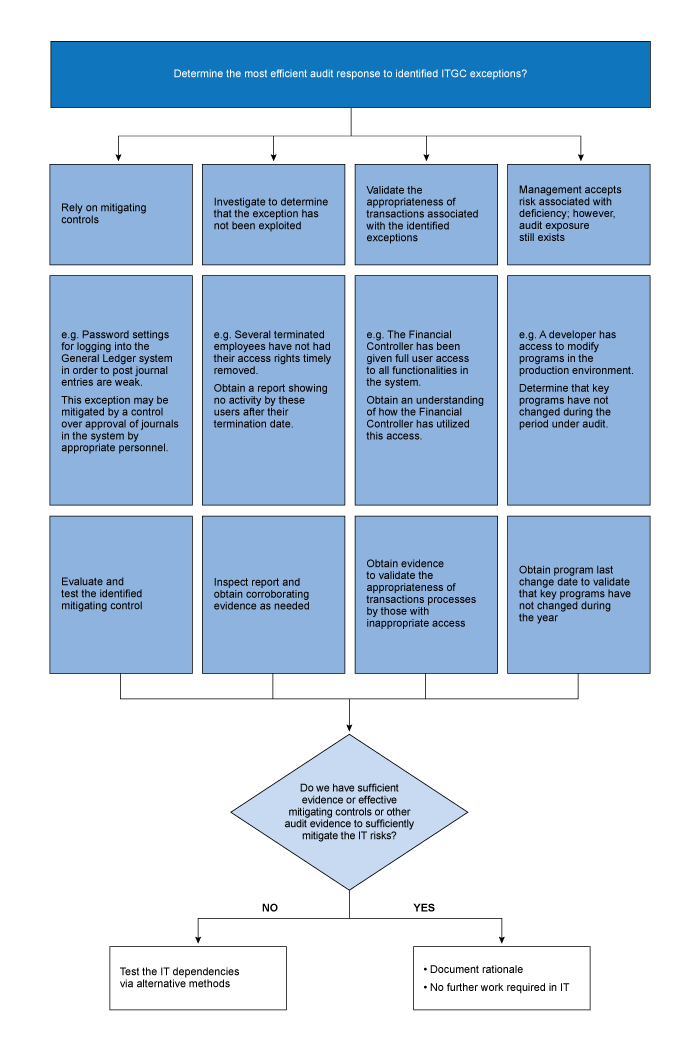

Refer to the chart below for guidance on how to determine if ITGC deficiencies have not been exploited.

IT deficiencies within off‑the‑shelf packages

Our evaluation of deficiencies for off‑the‑shelf packages is no different than those associated with bespoke and/or customized applications. However, control deficiencies within these types of applications are typically related to privileged access. We need to consider the likelihood, not just magnitude, of a possible exception when evaluating the risks associated with inappropriate access rights, including high powered access rights and potential segregation of duties conflicts. Requesting assistance from IT Audit may be helpful under these circumstances.

Assessing ITGC deficiencies

Examples of potential deficiencies in internal control:

-

A person within the entity has been identified as having “super user” access: The existence of privileged access is not a “de facto” control deficiency. All applications have privileged user accounts built in. A deficiency only exists when such privileged access is inappropriate. There may be compensating controls in place: e.g. all entries are logged by the application; oversight of log by management. If we are able to evidence that the person had not used that “super‑user” access during the year, the risk associated with this deficiency is low.

-

Multiple users within finance share one log‑in and password, so when a person is transferred to another department, they are still able to access the application: There may be compensating controls in place, e.g. review of activity logs by management, BPRs performed at a sufficiently high level of precision to detect whether unauthorized entries were posted.

-

Back‑ups of critical data are not made: If there had been no need for the client in the current year to restore back‑ups, then we might recommend to them that back‑ups be made going forward as a safeguard against potential future loss of data. However, if there had been issues during the past year, whether a deficiency exists would depend on how successfully the entity was able to restore their data.

If the engagement team has identified one or more deficiencies in ITGCs, we still assess whether the relevant IT dependencies can be relied upon, because the entity may have compensating controls that reduce the impact of the ITGC deficiencies, e.g. management review of logs, or alternative testing methods could be applied to these IT dependencies to avoid increasing substantive testing. Refer to OAG Audit 4028.4 for guidance on how to test IT dependencies when ITGCs are deficient or do not exist.

The existence of privileged access is not a “de facto” deficiency in internal control. Reasonable professional judgment is needed to evaluate risks associated with privileged access (both fraud risks and the risks of inadvertent error or data corruption), and the nature and extent of controls needed to mitigate those risks. Some factors to consider in making those judgments include:

-

Is there a legitimate business purpose for direct access to data? If management believes that 100% restriction from data access is operationally impractical or could threaten IT environment stability, are there at least partial restrictions enforced; such as constraining access to specific applications or platforms and segregating responsibilities?

-

What are the inherent risks associated with the direct access to data, including factors such as:

-

Nature and volume of access activities (e.g., normal application maintenance versus frequent “clean‑up” or “data fix” activities)

-

-

Importance/significance of the impacted data to financial statement assertions

-

Breadth of access rights (e.g., number of cycles or business processes impacted)

-

Availability of reliable information about the population of data changes

-

Level of susceptibility of related assets and liabilities to loss or fraud

-

IT environment and application complexity; effectiveness of built‑in data integrity controls;

-

vulnerability of data to access through indirect means

-

History of misstatements due to errors or fraud related to data access

-

-

Are the people with access to the database and the underlying data files appropriate and authorized based on job responsibilities and management’s approved intent? Is direct access restricted to those few individuals responsible for legitimate IT maintenance activities? Are those individuals otherwise segregated from:

-

Finance or accounting responsibilities

-

Responsibility for operating or reviewing controls over the processing of computerized data, such as reconciliations and interface controls

-

The ability to modify the flow of data processing in relation to the relevant data, such as through programmer access rights or "superuser" status

-

-

The ability to change automated controls, such as through programmer or configuration access rights

-

Access to physical assets controlled via the application or to sensitive preprinted forms or checks

-

The ability to authorize or process transactions via other access rights (e.g., using the applications or manually outside the IT environment)

-

The ability to grant/modify user access

-

The ability to change or delete application logs that track data access activities

-

The ability to add, delete or modify user access security privileges

-

-

Are there controls in place to periodically review data access rights to determine if they remain consistent with job responsibilities and management’s approved intent?

-

Is there competent, diligent supervision of those with data access rights?

-

Are there controls in place to provide access only on a temporary, as‑needed basis (e.g., broad access is granted on an exception basis to address a specific problem and then is promptly revoked)?

-

Are there controls in place to independently track and monitor the activities of those accessing data directly—either through reliable application logs, or through manual logging by individuals both independent of those with the access rights and sufficiently skilled to detect errors or unauthorized activity? (If system degradation is a concern against system‑based logging, has the company considered the approach of capturing logging in a separate protected server?)

-

Are background checks or other controls in place to properly consider the integrity of individuals with sensitive access rights?

-

Are there controls in place to ensure that all people with broad data access are informed, understand, and acknowledge that accessing or changing data files outside of the normal, documented process would have very serious consequences? Are such expectations regularly communicated and reinforced?

-

Is there a formal change management process in place to control data changes? Are formal approvals obtained for all changes, from the requesting parties and IT (to document the change was needed and why) and user management (to verify the change was made correctly)?

-

Are there controls in place such as a report of all standing or accumulated data elements changed from one period to the next that is reviewed to ensure no unauthorized changes were made (e.g., electronic notification, or review of a manual log where the volume of changes is reasonable and individuals with broad access cannot access or change the log)? If management asserts that such a reliable detective control is difficult to implement due to the volume of changes or the difficulty of interpreting change logs, is there a satisfactory alternative such as monitoring changes to a subset of the data elements that are higher risk?

-

Are there other controls (manual or automated) to ensure data has not been changed other than as intended (e.g., reconciliations with data from other well‑controlled applications or an external source)?

Factors such as these are relevant to evaluating first whether a deficiency in internal control exists and, if so, the severity of the deficiency. Deficiencies in internal control might exist in the design of controls (e.g., direct and unmonitored access to data is provided to individuals who also have the ability to process financial transactions) or in operating effectiveness (e.g., a breakdown in controls designed to monitor and detect unauthorized activity related to data access). The severity of a deficiency related to direct data access to financially significant applications generally needs to be evaluated directly in relation to the potential misstatement of the account by assertion, since restricting access to transactional data is typically related directly to achieving relevant financial statement assertions. It is not uncommon for compensating, manual business process controls (e.g., business performance reviews, transaction analyses, reconciliations, et al) to be an important part of the evaluation of data access‑related deficiencies, particularly for transaction cycles that are most prone to fraud risk. Note: It is very important that the effectiveness of any such compensating controls is not compromised by the same data access deficiencies that are being evaluated (for example, an individual with inappropriate access to data is the same individual performing the detective compensating controls).

A key to evaluating deficiencies in this area is whether management can demonstrate, through a sufficient balance of controls and qualitative factors, that the risk of a material misstatement of the financial statements from unauthorized or incorrect changes to accounting data via direct data access has been adequately mitigated. In many cases, the control objective will be achieved through multiple layers of controls that work together to sufficiently mitigate the risk. All such determinations require a high degree of judgment, grounded in a thorough understanding of the entity’s approach to mitigating the risks of fraud and financial statement misstatement associated with direct data access.

System performance degradation is a common argument against implementing automated auditing or logging tools. Another concern is that the volume of information logged would be too large to be reasonably monitored or reviewed. It may be possible in most environments, however, to reduce the volume of direct access activities by implementing many of the controls listed above around access and change control, such that automated logging and reviewing would be less cumbersome.