Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

5035.1 Identify controls that address risks of materials misstatement at the assertion level

Sep-2022

In This Section

Controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level

Understanding and evaluating business performance review controls

CAS Guidance

The control activities component includes controls that are designed to ensure the proper application of policies (which are also controls) in all the other components of the entity’s system of internal control, and includes both direct and indirect controls (CAS 315.A147).

|

Example: The controls that an entity has established to ensure that its personnel are properly counting and recording the annual physical inventory relate directly to the risks of material misstatement relevant to the existence and completeness assertions for the inventory account balance. |

The auditor’s identification and evaluation of controls in the control activities component is focused on information processing controls, which are controls applied during the processing of information in the entity’s information system that directly address risks to the integrity of information (i.e., the completeness, accuracy and validity of transactions and other information). However, the auditor is not required to identify and evaluate all information processing controls related to the entity’s policies that define the flows of transactions and other aspects of the entity’s information processing activities for the significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures (CAS 315.A148).

There may also be direct controls that exist in the control environment, the entity’s risk assessment process or the entity’s process to monitor the system of internal control, which may be identified in accordance with paragraph 26. However, the more indirect the relationship between controls that support other controls and the control that is being considered, the less effective that control may be in preventing, or detecting and correcting, related misstatements (CAS 315.A149).

|

Example: A sales manager’s review of a summary of sales activity for specific stores by region ordinarily is only indirectly related to the risks of material misstatement relevant to the completeness assertion for sales revenue. Accordingly, it may be less effective in addressing those risks than controls more directly related thereto, such as matching shipping documents with billing documents. |

Paragraph 26 also requires the auditor to identify and evaluate general IT controls for IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment that the auditor has determined to be subject to risks arising from the use of IT, because general IT controls support the continued effective functioning of information processing controls. A general IT control alone is typically not sufficient to address a risk of material misstatement at the assertion level (CAS 315.A150).

The controls that the auditor is required to identify and evaluate the design, and determine the implementation of, in accordance with paragraph 26 are those (CAS 315.A151):

-

Controls which the auditor plans to test the operating effectiveness of in determining the nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures. The evaluation of such controls provides the basis for the auditor’s design of test of control procedures in accordance with CAS 330. These controls also include controls that address risks for which substantive procedures alone do not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence.

-

Controls include controls that address significant risks and controls over journal entries. The auditor’s identification and evaluation of such controls may also influence the auditor’s understanding of the risks of material misstatement, including the identification of additional risks of material misstatement (see paragraph A95). This understanding also provides the basis for the auditor’s design of the nature, timing and extent of substantive audit procedures that are responsive to the related assessed risks of material misstatement.

-

Other controls that the auditor considers are appropriate to enable the auditor to meet the objectives of paragraph 13 with respect to risks at the assertion level, based on the auditor’s professional judgment.

Controls in the control activities component are required to be identified when such controls meet one or more of the criteria included in paragraph 26(a). However, when multiple controls each achieve the same objective, it is unnecessary to identify each of the controls related to such objective (CAS 315.A152).

Examples of controls in the control activities component include authorizations and approvals, reconciliations, verifications (such as edit and validation checks or automated calculations), segregation of duties, and physical or logical controls, including those addressing safeguarding of assets (CAS 315.A153).

Controls in the control activities component may also include controls established by management that address risks of material misstatement related to disclosures not being prepared in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework. Such controls may relate to information included in the financial statements that is obtained from outside of the general and subsidiary ledgers (CAS 315.A154).

Regardless of whether controls are within the IT environment or manual systems, controls may have various objectives and may be applied at various organizational and functional levels (CAS 315.A155).

OAG Guidance

As explained in OAG Audit 5031 obtaining an understanding of the entity’s system of internal control allows us to identify and assess risks of material misstatement specific to the entity as well as facilitates the development of audit responses that effectively and efficiently address the identified risks of material misstatements. One of the components of the entity’s system of internal control that we are required to understand is control activities. As noted by CAS 315.A147 this component includes controls that are designed to ensure the proper application of policies in all other components of the entity’s system of internal control and includes both direct and indirect controls. When obtaining our understanding of the control activities component, we focus on identifying controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level. The detailed guidance covering the types of the controls that we would generally identify within the control activities component is included in the block below Controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level.

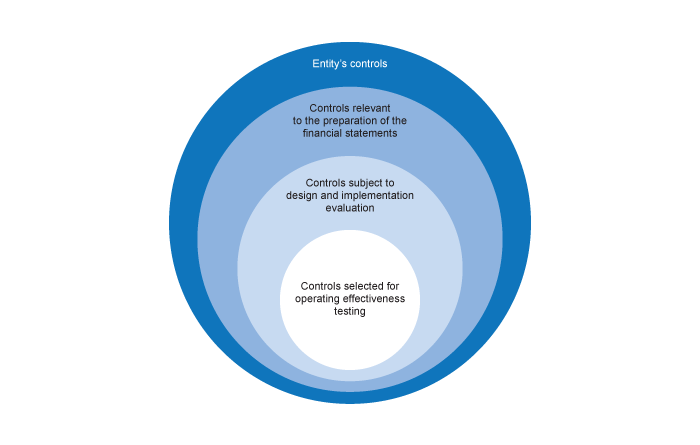

Not all controls that we identify during our audit would be included in the control activities component of the entity’s system of internal control subject to design and implementation evaluation. The relationship of the controls that the entity has designed and those that we would identify within the control activities component is depicted on the diagram below:

In order to ensure proper functioning of the business, the entity puts in place various controls referred to as the entity’s controls in the diagram above. The ‘entity’s controls’ typically address a variety of business and operational risks, some of which are not meant to address risks of material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements. When planning and performing our audit we focus on risks of material misstatement at the financial statement and assertion levels and the subset of the entity’s controls that address these risks. This subset of controls are referred to as controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements in the diagram above. We typically identify such controls when obtaining an understanding of the components of the entity’s system of internal control especially when obtaining understanding of the flow of transactions and business processes within the information system and communication component. See OAG Audit 5034 for additional guidance related to understanding information processing activities within business processes.

We identify controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level and are part of the control activities component in accordance with CAS 315.26(a). It is these controls that are subject to design and implementation evaluation. As explained in the block below Controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level, in addition to these controls other controls could be included in this subset based on specific CAS requirements other than CAS 315. See OAG Audit 5035.5 for further guidance on evaluation of design and implementation. A final subset of the controls presented on the chart are those controls that we plan to rely on when obtaining audit evidence and therefore would be selected for operating effectiveness testing. For further guidance on these controls see the block below Controls selected for operating effectiveness testing.

The table below summarizes the expected evidence for each of the control subsets mentioned above:

|

Control subset |

Procedures to be performed for the purposes of the audit |

|

Entity’s controls that are not relevant to the preparation of the financial statements |

|

|

Controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements |

|

| Controls that address the risk of material misstatement at the assertion level and subject to design and implementation evaluation (see the block below Controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level) |

|

|

Controls selected for operating effectiveness testing (i.e., controls on which we plan to place reliance) |

|

When performing the expected audit procedures for the individual control subset we need to be mindful that the concepts of design and implementation are not the same as testing the operating effectiveness of an internal control. Each of the concepts is explained below:

-

Design: Evaluating the design effectiveness of controls within the control activities component is focused on whether they can prevent or detect and timely correct a material misstatement, due to error or fraud, of the financial statements.

-

Implementation: Based on our understanding of the control, and our professional judgment we validate, through inspection, observation or re‑performance of at least one instance of the control, to obtain evidence that the entity has placed the control into operation as designed. We may also trace a transaction through a business process as evidence that the control has been implemented as designed.

Operating effectiveness: Testing the operating effectiveness of a control involves testing its operation over time during the audit period to determine whether it is operating as designed. If we intend to place reliance on the control, we test an appropriate sample of instances of the control operating during the audit period. See OAG Audit 6053 for guidance on sample sizes when testing operating effectiveness of a control.

CAS Requirement

The auditor shall obtain an understanding of the control activities component, through performing risk assessment procedures, by (CAS 315.26):

(a) Identifying controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level in the control activities component as follows:

(i) Controls that address a risk that is determined to be a significant risk;

(ii) Controls over journal entries, including non-standard journal entries used to record non-recurring, unusual transactions or adjustments;

(iii) Controls for which the auditor plans to test operating effectiveness in determining the nature, timing and extent of substantive testing, which shall include controls that address risks for which substantive procedures alone do not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence; and

(iv) Other controls that the auditor considers are appropriate to enable the auditor to meet the objectives of paragraph 13 with respect to risks at the assertion level, based on the auditor’s professional judgment;

CAS Guidance

Regardless of whether the auditor plans to test the operating effectiveness of controls that address significant risks, the understanding obtained about management’s approach to addressing those risks may provide a basis for the design and performance of substantive procedures responsive to significant risks as required by CAS 330. Although risks relating to significant non‑routine or judgmental matters are often less likely to be subject to routine controls, management may have other responses intended to deal with such risks. Accordingly, the auditor’s understanding of whether the entity has designed and implemented controls for significant risks arising from non‑routine or judgmental matters may include whether and how management responds to the risks. Such responses may include (CAS 315.A158):

- Controls, such as a review of assumptions by senior management or experts.

- Documented processes for accounting estimations.

- Approval by those charged with governance.

|

Example: Where there are one-off events such as the receipt of a notice of a significant lawsuit, consideration of the entity’s response may include such matters as whether it has been referred to appropriate experts (such as internal or external legal counsel), whether an assessment has been made of the potential effect, and how it is proposed that the circumstances are to be disclosed in the financial statements. |

CAS 240 requires the auditor to understand controls related to assessed risks of material misstatement due to fraud (which are treated as significant risks), and further explains that it is important for the auditor to obtain an understanding of the controls that management has designed, implemented and maintained to prevent and detect fraud (CAS 315.A159).

Controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level that are expected to be identified for all audits are controls over journal entries, because the manner in which an entity incorporates information from transaction processing into the general ledger ordinarily involves the use of journal entries, whether standard or non‑standard, or automated or manual. The extent to which other controls are identified may vary based on the nature of the entity and the auditor’s planned approach to further audit procedures (CAS 315.A160).

|

Example: In an audit of a less complex entity, the entity’s information system may not be complex and the auditor may not plan to rely on the operating effectiveness of controls. Further, the auditor may not have identified any significant risks or any other risks of material misstatement for which it is necessary for the auditor to evaluate the design of controls and determine that they have been implemented. In such an audit, the auditor may determine that there are no identified controls other than the entity’s controls over journal entries. |

In manual general ledger systems, non‑standard journal entries may be identified through inspection of ledgers, journals, and supporting documentation. When automated procedures are used to maintain the general ledger and prepare financial statements, such entries may exist only in electronic form and may therefore be more easily identified through the use of automated techniques. (CAS 315.A161).

|

Example: In the audit of a less complex entity, the auditor may be able to extract a total listing of all journal entries into a simple spreadsheet. It may then be possible for the auditor to sort the journal entries by applying a variety of filters such as currency amount, name of the preparer or reviewer, journal entries that gross up the balance sheet and income statement only, or to view the listing by the date the journal entry was posted to the general ledger, to assist the auditor in designing responses to the risks identified relating to journal entries. |

The auditor determines whether there are any risks of material misstatement at the assertion level for which it is not possible to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence through substantive procedures alone. The auditor is required, in accordance with CAS 330,42 to design and perform tests of controls that address such risks of material misstatement when substantive procedures alone do not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence at the assertion level. As a result, when such controls exist that address these risks, they are required to be identified and evaluated (CAS 315.A162).

In other cases, when the auditor plans to take into account the operating effectiveness of controls in determining the nature, timing and extent of substantive procedures in accordance with CAS 330, such controls are also required to be identified because CAS 330.43 requires the auditor to design and perform tests of those controls (CAS 315.A163).

|

Examples: The auditor may plan to test the operating effectiveness of controls:

|

The auditor’s plans to test the operating effectiveness of controls may also be influenced by the identified risks of material misstatement at the financial statement level. For example, if deficiencies are identified related to the control environment, this may affect the auditor’s overall expectations about the operating effectiveness of direct controls (CAS 315.A164).

Other controls that the auditor may consider are appropriate to identify, and evaluate the design and determine the implementation, may include (CAS 315.A165):

-

Controls that address risks assessed as higher on the spectrum of inherent risk but have not been determined to be a significant risk;

-

Controls related to reconciling detailed records to the general ledger; or

-

Complementary user entity controls, if using a service organization.

Controls in the control activities component are identified in accordance with paragraph 26. Such controls include information processing controls and general IT controls, both of which may be manual or automated in nature. The greater the extent of automated controls, or controls involving automated aspects, that management uses and relies on in relation to its financial reporting, the more important it may become for the entity to implement general IT controls that address the continued functioning of the automated aspects of information processing controls. Controls in the control activities component may pertain to the following (CAS 315.Appendix 3.20):

-

Authorization and approvals. An authorization affirms that a transaction is valid (i.e., it represents an actual economic event or is within an entity’s policy). An authorization typically takes the form of an approval by a higher level of management or of verification and a determination if the transaction is valid. For example, a supervisor approves an expense report after reviewing whether the expenses seem reasonable and within policy. An example of an automated approval is when an invoice unit cost is automatically compared with the related purchase order unit cost within a pre‑established tolerance level. Invoices within the tolerance level are automatically approved for payment. Those invoices outside the tolerance level are flagged for additional investigation.

Reconciliations – Reconciliations compare two or more data elements. If differences are identified, action is taken to bring the data into agreement. Reconciliations generally address the completeness or accuracy of processing transactions.

-

Verifications – Verifications compare two or more items with each other or compare an item with a policy, and will likely involve a follow‑up action when the two items do not match or the item is not consistent with policy. Verifications generally address the completeness, accuracy, or validity of processing transactions.

-

Physical or logical controls, including those that address security of assets against unauthorized access, acquisition, use or disposal. Controls that encompass:

-

The physical security of assets, including adequate safeguards such as secured facilities over access to assets and records.

-

The authorization for access to computer programs and data files (i.e., logical access).

-

The periodic counting and comparison with amounts shown on control records (for example, comparing the results of cash, security and inventory counts with accounting records).

-

The extent to which physical controls intended to prevent theft of assets are relevant to the reliability of financial statement preparation depends on circumstances such as when assets are highly susceptible to misappropriation.

-

Segregation of duties. Assigning different people the responsibilities of authorizing transactions, recording transactions, and maintaining custody of assets. Segregation of duties is intended to reduce the opportunities to allow any person to be in a position to both perpetrate and conceal errors or fraud in the normal course of the person’s duties.

For example, a manager authorizing credit sales is not responsible for maintaining accounts receivable records or handling cash receipts. If one person is able to perform all these activities the person could, for example, create a fictitious sale that could go undetected. Similarly, salespersons should not have the ability to modify product price files or commission rates.

Sometimes segregation is not practical, cost effective, or feasible. For example, smaller and less complex entities may lack sufficient resources to achieve ideal segregation, and the cost of hiring additional staff may be prohibitive. In these situations, management may institute alternative controls. In the example above, if the salesperson can modify product price files, a detective control activity can be put in place to have personnel unrelated to the sales function periodically review whether and under what circumstances the salesperson changed prices.

Certain controls may depend on the existence of appropriate supervisory controls established by management or those charged with governance. For example, authorization controls may be delegated under established guidelines, such as investment criteria set by those charged with governance; alternatively, non‑routine transactions such as major acquisitions or divestments may require specific high‑level approval, including in some cases that of shareholders (CAS 315.Appendix 3.21).

OAG Guidance

As part of obtaining a sufficient understanding of the entity’s information systems and the related business processes relevant to financial reporting, we normally obtain an understanding of controls within the business process/sub‑processes. We focus on controls that individually or in combination with others are likely to prevent or, detect and correct on a timely basis, material misstatements in the financial statements. In determining whether controls will prevent or detect misstatements both due to error and fraud, we consider their relationship with the relevant financial statement assertions.

CAS 315.26(a) requires us to understand, including evaluation of design and determining implementation, controls that address risks of material misstatement at the assertion level in the control activities component as follows:

-

Controls that address a risk that is determined to be a significant risk

-

Controls over journal entries, including non‑standard journal entries used to record non‑recurring, unusual transactions or adjustments

-

Controls for which we plan to test operating effectiveness, including controls that address risks for which substantive procedures alone do not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence

-

Other controls based on our professional judgment that we consider are appropriate to identify, and evaluate the design and determine the implementation, which may include:

-

Controls that address risks assessed as higher on the spectrum of inherent risk but have not been determined to be a significant risk (i.e., elevated risks);

-

Controls related to reconciling detailed records to the general ledger; or

-

Complementary user entity controls, if using a service organization.

-

When identifying controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements, various CASs require that we understand controls in the following specific areas:

-

Identified controls in the control activities component over management’s process for making accounting estimates (see OAG Audit 7073.1; CAS 540.13(i))

-

Controls, if any, that management has established to identify, account for, disclose and authorize related party transactions and transactions outside the normal course of business (see OAG Audit 7532; CAS 550.14)

-

Identified controls in the control activities component at the user entity that relate to services provided by a service organization, including those that are applied to transactions processed by the service organization (See OAG Audit 6042; CAS 402.10)

-

For group audits, group‑wide controls designed, implemented and maintained by group management over group financial reporting (see OAG Audit 2332; CAS 600.17)

To the extent any of the controls we identify and understand in the above areas are determined to represent controls in the control activities component, we are required to evaluate their design effectiveness and determine whether they have been implemented, as described in OAG Audit 5035.5. Conversely, to the extent any of these controls we identify and understand are not determined to represent controls in the control activities component, we are not required to evaluate their design effectiveness or to determine whether they have been implemented as described.

OAG Guidance

Business performance reviews

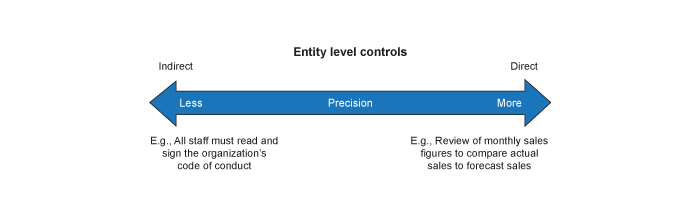

Business performance reviews ("BPRs") can represent Indirect Entity Level Controls (ELCs) typically included in the entity’s process to monitor the system of internal control, or direct ELCs typically included in the control activities component of the entity’s system of internal control.

Although their purposes may overlap, there is an important distinction between BPRs, which are a type of control activity, and monitoring of controls. The objective of monitoring of controls is to assess effective operation of internal controls whereas BPRs are directed at determining whether certain metrics (financial or non‑financial) are being met (e.g., is the entity meeting its budget). In some cases, BPRs may also provide information that enables management to identify deficiencies in internal control. Although controls such as monitoring of super‑user activity involve monitoring activities they are considered ITGCs and not BPRs.

When designed, implemented and operating effectively, BPRs may operate at a sufficient level of precision to adequately prevent, or detect and correct on a timely basis, material misstatements to one or more relevant assertions for FSLIs. Testing the operating effectiveness of BPRs that operate at a level of precision that, by themselves, would prevent or detect a material misstatement on a timely basis often will allow us to reduce the number of information processing controls that we might otherwise test. We may be able to rely on BPRs that are designed to prevent or detect and correct, on a timely basis, a material misstatement that could arise when information processing controls are either missing or deficient.

It is important we do not begin testing the operating effectiveness of any control, including a BPR, until we have first assessed its design effectiveness. It is important that the entity is able to describe the control design in sufficient detail to allow us to assess and document the basis for our conclusion about the design effectiveness of the BPR. Depending on the importance of the control, simply explaining or evaluating the design of a control as "Jane Doe, Controller, reviews and approves the group reporting package," or "The divisional controller performs a variance analysis," does not provide sufficient detail about what controls are performed and therefore does not identify the information needed to assess whether the control is designed in a way that is likely to prevent, or detect and correct, on a timely basis, a material misstatement. In addition to a detailed description of the activities performed, it is important to understand the actions taken when potential variances or other operating anomalies are identified and what level of variance or anomaly will trigger further investigation and/or correction (i.e., the level of precision with which the control is designed to operate).

|

Example: Contract review committee reviews all sales contracts with more than $ 50,000 value to identify and approve the terms of all sales contracts that contain multiple performance obligations, entity‑wide, to ensure (among other objectives) that the accounting implications are identified and subjected to appropriate accounting processes and controls. The contract review committee comprises members who are knowledgeable and experienced in accounting for revenues under IFRS 15 and are independent of the entity’s sales function. |

As a first step in determining whether we can rely upon a BPR in our audit, we begin by evaluating its design effectiveness. The factors that could be relevant to our evaluation of the design effectiveness of a BPR include those to be considered for other types of controls discussed in this section as well as other factors specific to BPRs.

The table below includes a summary of factors to consider when evaluating design and implementation of a BPR:

-

The objective(s) of the control;

-

Component(s) of the entity (individually or consolidated) covered by the control being evaluated;

-

Account(s) at the component(s) covered by the control;

-

The authority and competence of the person that performs the control;

-

The frequency with which the control operates;

-

The specific procedures that are performed and at what level of precision and the related controls (i.e., a process consists of activities and sub‑processes but not all of them are likely to be controls in the control activities component)

-

Reliability of the information used in the performance of the control and its source; and

-

The evidence available to demonstrate that the control operates as intended

1. The objective(s) of the control

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

The objective(s) of the control is (are) important because it describes what management intends to accomplish in performing the control (e.g., prevent or detect and correct on a timely basis, a misstatement in a significant FSLI(s)) in preparing the entity’s financial statements in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework.

|

2. Component(s) of the entity (individually or consolidated) covered by the control being evaluated

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

Components are described in OAG Audit 2323. If acomponent is not covered by the control, then we are not able to rely upon the control as a source of audit evidence for that component. |

3. Account(s) at the component(s) covered by the control

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

If an account and its transactions are not covered by the control, then we are not able to rely upon the control related to that account. |

4. The authority and competence of the person that performs the control

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

The knowledge and experience required of the personnel responsible for performing the control (i.e., control operators) depend on the objective(s) of the control, the complexity of the FSLI and the relative importance of the control. A control that is simple to execute, has lower risk associated with the account, likely requires less knowledge and experience than a control that is complex to execute and has higher risk associated with the account. Furthermore, execution of some controls may require specialized skills or technical expertise. If the person performing the control does not possess the necessary authority and competence to perform the control effectively, then the control is not well designed, and we are not able to rely upon the control (consider whether a control deficiency needs to be identified). The authority of the personnel responsible for performing the control is also considered when assessing the design of the control. We evaluate whether the responsible personnel have the appropriate authorities that are commensurate with their job responsibilities to execute the specific activities. Additionally, segregation of duties would be considered when assessing the person or people performing the control. For example, if we plan to obtain audit evidence from a BPR as a result of identified operating deficiencies in an information processing control which we initially planned to rely on and the person performing both of these controls is the same, the BPR may not adequately compensate for the information processing control deficiency. |

5. The frequency with which the control operates

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

The frequency of the control may impact its effectiveness in preventing or detecting a misstatement or whether it is effective in compensating for a transaction level control deficiency depending on the objective of the control (e.g. an annual BPR may not sufficiently compensate for a multiple times per day information processing control designed to timely detect an error). |

6. The specific procedures that are performed and at what level of precision and the related controls (i.e., a process consists of activities and sub‑processes but not all of them are likely to be controls within the control activities component).

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

In order for the control to be effective in preventing or detecting a misstatement, the specific procedures which are controls performed must be designed and executed to address the objective of the control. Additionally, they must be sufficiently precise to detect a material misstatement. Assessing whether a control’s precision is sufficient involves significant judgment. Factors that may be considered when evaluating the level of precision at which a BPR operates, include:

The sufficiency of the level of precision at which the control operates can be evaluated based on the risk that the control will fail to detect smaller misstatements that could aggregate to a material misstatement (i.e., aggregation risk). |

7. Reliability of the information used in the performance of the control and its source (IT dependency).

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

Consider the following questions when evaluating how management obtains evidence that information used in the performance of the control is reliable:

|

In order for the control to be effectively designed, management needs to take steps to check that the data used in the control is reliable. Therefore, as part of the design evaluation, we understand and evaluate how management obtains assurance that system‑generated reports and other information used in and important to the operation of the control is reliable (i.e., complete and accurate). |

8. The evidence available to demonstrate that the control operates as intended.

|

Considerations/Factors |

Impact on Design |

|

What is the available evidence for all relevant sub-activities (particularly for more complex controls)? |

In order for us to use a control as part of addressing risk, we need to evaluate whether the control is designed in a way that will provide sufficient evidence to allow us to test its operating effectiveness. |

Although the table above is focused on specific factors that may affect the evaluation of the design effectiveness of BPRs, these factors may also be relevant when assessing other types of review controls (e.g., controls over the review of journal entry submissions, spreadsheet calculations, or the methods, assumptions or data used to develop estimates).

We consider relevant factors as part of our evaluation of the design and implementation of the control. When evaluating the BPR design we also need to assess whether the control is likely to achieve the intended objectives if it is consistently executed. In making this assessment we consider the following, among other relevant factors:

-

Can the control objective(s) feasibly be met?

-

Is there a demonstrated history of effective operation of the control? What is the evidence?

-

Has the control previously failed to prevent or detect misstatements for which the control was intended to prevent or detect?

-

Are there other controls (supervisory or otherwise) that are designed to monitor the effectiveness of the control?

-

Are there other controls that work in conjunction with the control to achieve the control objective(s)?

OAG Guidance

When selecting controls to test for operating effectiveness, we focus on testing only those controls that are designed to prevent or detect on a timely basis material misstatements, individually or in the aggregate, for a relevant assertion. We select controls for operating effectiveness testing that provide the most effective or efficient means of obtaining audit evidence for one or more relevant financial statement assertions for one or more FSLIs. As explained in the block Overview above, those controls, also commonly referred to as selected controls, are a sub‑group of the controls subject to design and implementation evaluation, which in turn is a sub‑group of the controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements

Judgment is required to identify and select controls to test. For example, it is not necessary to test controls that:

a. Do not address the identified risk

b. Address the identified risk, but we have other sources of audit evidence available (e.g., other controls or substantive evidence) that provide a more effective and efficient source of obtaining sufficient evidence.

Example:

There is a risk of material misstatement over purchases and payables related to purchases not being appropriately authorized.

We identify two controls during our walkthrough to understand the end‑to‑end purchases and payables business process:

-

Control A is an automated control that requires a supervisory approval before an item can be requested for purchase (i.e., before a purchase order can be processed).

-

Control B is a manual control executed by the director of the purchasing department that verifies all items requested for purchase are using agreed suppliers, that appropriate approvals have been obtained (the same risk that control A covers) and that bank details for payment have not changed.

Here, on the basis that control B is designed and implemented to address this risk of material misstatement, we would likely plan to test control B for operating effectiveness. Testing of control A would not be necessary because a sufficient appropriate level of controls reliance can be obtained from the effective operation of control B throughout the audit period.

Not all controls that we evaluate for design and implementation will be selected for operating effectiveness testing. For example, although we are required to assess design and determine implementation of a control addressing relevant assertions for a significant risk, we would not necessarily select this control and test it for operating effectiveness if we conclude we can effectively and efficiently obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence by performing substantive audit procedures. A selected control therefore is a control for which we plan to test the operating effectiveness because it is judged to be:

-

An effective way of obtaining audit evidence to address the assessed risk of material misstatement at the assertion level;

-

Designed and operating at the appropriate level of precision;

-

Responsive to the identified risk of material misstatement, due to error or fraud;

-

Efficient to test in order to achieve the expected controls reliance.

When selecting controls for operating effectiveness testing, first consider whether to place reliance on Direct ELCs, as they are often designed to cover multiple assertions relating to an FSLI, provided the control is designed to operate at a sufficient level of precision. OAG Audit 6051 provides additional guidance on selecting controls to test

When selecting controls for operating effectiveness testing we may follow the following approach that summarizes the practical approach to the guidance provided above:

-

We obtain an understanding of the entity’s controls relevant to the preparation of the financial statements when performing procedures to understand and evaluate the entity’s system of internal controls.

-

Once we have obtained an understanding of the entity and its environment, and the entity’s system of internal control and determined the significant classes of transactions, account balances and disclosures and the relevant assertions, we identify those direct ELC and information processing controls that address the identified risks of material misstatement at the assertion level. We then select controls that we believe provide an effective and efficient way of obtaining audit evidence addressing the identified risks of material misstatement at the assertion level.

-

For those controls selected for testing of operating effectiveness, evaluate if the Direct ELCs are designed effectively and if they are sufficiently precise to prevent or detect and correct, on a timely basis, the identified risk of material misstatements at the assertion level. A Business Performance Review (BPR) is an example of such a direct ELC. The level of assurance obtained from testing the operating effectiveness of a BPR depends on a number of factors – see the block above Understanding and evaluating business performance review controls for further guidance.

-

Consider the level of evidence obtained from testing direct ELCs and determine whether further controls evidence for relevant assertions is needed (e.g., if the ELC is not operating at a sufficient level of precision, consider also testing information processing controls).

-

Both direct ELCs and information processing controls selected for testing of operating effectiveness are subject to design and implementation evaluation in accordance with the requirement of CAS 315.26(d).

On a recurring audit where we have relied on controls in past audits, it may be effective and efficient to test the operating effectiveness of such controls at the same time we update our evaluation of their design and determining whether they have been implemented. Because the procedures to evaluate design and implementation of controls and the procedures to test their operating effectiveness have two different objectives, it is important that our documentation of these procedures reflect evidence that supports the audit work performed to address each of these objectives. When we perform procedures concurrently before the end of the period, we need to consider performing update testing of the operating effectiveness of these controls (Refer to OAG Audit 6055 for guidance on update testing of controls).

OAG Guidance

We evaluate early in the audit whether identified Direct ELCs are designed effectively, including a sufficient level of precision to address risks of material misstatements at the assertion level because the result of that assessment is an important consideration in our audit planning process. An integral part of our consideration of direct ELCs is a focus on controls important to the prevention and detection of material misstatements to the financial statements due to error or fraud, including controls to address the risk of management override (where appropriate). Direct ELCs allow us to understand the entity’s controls over financial information and the more precise the direct ELC, the more audit evidence we typically need to test operating effectiveness throughout the audit period. We may be able to test fewer information processing controls if the direct ELC is precise enough to prevent or detect material misstatements. The impact of our evaluation and testing of direct ELCs on the nature, timing, and extent of our testing of information processing controls may vary significantly depending upon the specific circumstances of the entity, the applicable FSLI and/or the assertions relevant to the risk of material misstatement. See OAG Audit 5040 for a further understanding of relevant assertions and how they affect our audit procedures. Our evaluation of the direct ELCs and the level of precision at which they operate affects the nature and extent of testing that we otherwise may need to perform on controls at the information processing level.

The following continuum depicts the impact of ELCs and the level of precision at which they operate on a relevant assertion for a significant FSLI:

At one end of the continuum are direct ELCs that are designed to operate at a level of precision that would, by themselves, prevent or detect, on a timely basis, material misstatements to one or more relevant assertions. In the middle of the continuum are controls that are intended to monitor the effectiveness of other controls, or those controls and procedures designed to identify possible deviations in information processing controls. At the other end of the continuum are indirect ELCs (e.g., controls within the control environment component) that are not directly related to any relevant assertion for any specific significant FSLI and, therefore, would not by themselves prevent or detect on a timely basis material misstatements to one or more relevant assertions.

ELCs may impact the nature, timing and extent of our testing of controls, regardless of where they fall upon the continuum. However, ELCs that operate at a level of precision that, by themselves, would prevent or detect a material misstatement on a timely basis often will allow us to reduce the number of information processing controls that we might otherwise test.

Consider the effectiveness of indirect ELCs in determining the nature, timing and extent of testing controls. For example, an indirect ELC where management has implemented a policy manual outlining the entity’s policies and procedures for required learning and continuing development of employees and management monitors completion of required training, this may provide indirect evidence that an employee performing a control related to reconciliation of the accounts payable subledger to the general ledger has been sufficiently trained. This audit evidence obtained from an indirect ELC may allow us to reduce the nature, timing and extent of testing we perform over the operating effectiveness of this reconciliation control (e.g., more inspection and less reperformance of individual instances of controls).

When the precision at which an ELC operates is close to or below our materiality limits, there is greater likelihood that the ELC will prevent or detect a material misstatement by itself and, therefore, less testing of information processing or application level controls may be necessary. If an ELC operates at a sufficient level of precision to prevent or detect a material misstatement on a timely basis and meets the control objectives related to one or more relevant financial statement assertions for a significant FSLI, testing of additional controls with respect to the same relevant assertions for that significant FSLI may not be necessary other than to obtain evidence about the effectiveness of controls over the completeness and accuracy of information or data used in the ELC (i.e., underlying data used by management in performing business performance reviews).

For most entities indirect ELCs and controls that monitor the effectiveness of other controls are significantly more prevalent than ELCs designed and operating at a level of precision to prevent or detect a material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Therefore, while selecting and testing some ELCs may allow us to effectively and efficiently obtain audit evidence, in many cases the presence of ELCs will not lead to the elimination of control testing at the information processing, application, database, operating system and network levels.