Annual Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

5035.5 Evaluate design and implementation of controls

Sep-2022

In This Section

Evaluate design and implementation of controls

Evaluate whether ITGCs are designed effectively and have been implemented

CAS Requirements

The auditor shall obtain an understanding of the control activities component, through performing risk assessment procedures, by (CAS 315.26):

(d) For each control identified in (a) or (c)(ii):

(i) Evaluating whether the control is designed effectively to address the risk of material misstatement at the assertion level, or effectively designed to support the operation of other controls; and

(ii) Determining whether the control has been implemented by performing procedures in addition to inquiry of the entity’s personnel.

CAS Guidance

Evaluating the design of an identified control involves the auditor’s consideration of whether the control, individually or in combination with other controls, is capable of effectively preventing, or detecting and correcting, material misstatements (i.e., the control objective) (CAS 315.A175).

The auditor determines the implementation of an identified control by establishing that the control exists and that the entity is using it. There is little point in the auditor assessing the implementation of a control that is not designed effectively. Therefore, the auditor evaluates the design of a control first. An improperly designed control may represent a control deficiency (CAS 315.A176).

Risk assessment procedures to obtain audit evidence about the design and implementation of identified controls in the control activities component may include (CAS 315.A177):

- Inquiring of entity personnel.

- Observing the application of specific controls.

- Inspecting documents and reports.

Inquiry alone, however, is not sufficient for such purposes.

The auditor may expect, based on experience from the previous audit or based on current period risk assessment procedures, that management does not have effectively designed or implemented controls to address a significant risk. In such instances, the procedures performed to address the requirement in paragraph 26(d) may consist of determining that such controls have not been effectively designed or implemented. If the results of the procedures indicate that controls have been newly designed or implemented, the auditor is required to perform the procedures in paragraph 26(b)‒(d) on the newly designed or implemented controls (CAS 315.A178).

The auditor may conclude that a control, which is effectively designed and implemented, may be appropriate to test in order to take its operating effectiveness into account in designing substantive procedures. However, when a control is not designed or implemented effectively, there is no benefit in testing it. When the auditor plans to test a control, the information obtained about the extent to which the control addresses the risk(s) of material misstatement is an input to the auditor’s control risk assessment at the assertion level (CAS 315.A179).

Evaluating the design and determining the implementation of identified controls in the control activities component is not sufficient to test their operating effectiveness. However, for automated controls, the auditor may plan to test the operating effectiveness of automated controls by identifying and testing general IT controls that provide for the consistent operation of an automated control instead of performing tests of operating effectiveness on the automated controls directly. Obtaining audit evidence about the implementation of a manual control at a point in time does not provide audit evidence about the operating effectiveness of the control at other times during the period under audit. Tests of the operating effectiveness of controls, including tests of indirect controls, are further described in CAS 330.45 (CAS 315.A180).

When the auditor does not plan to test the operating effectiveness of identified controls, the auditor’s understanding may still assist in the design of the nature, timing and extent of substantive audit procedures that are responsive to the related risks of material misstatement (CAS 315.A181).

|

Example: The results of these risk assessment procedures may provide a basis for the auditor’s consideration of possible deviations in a population when designing audit samples. |

OAG Guidance

As per CAS 315.26(c), for each control identified as part of control activities (refer to OAG Audit 5035.1 and OAG Audit 5035.2) we are required to evaluate whether the control is designed effectively to address the risk of material misstatement at the assertion level, or effectively designed to support the operation of other controls; and to determine whether the control has been implemented.

Evaluating the design of controls

When evaluating the design effectiveness of controls, we apply our professional judgment in considering the following factors as applicable to the type of control:

-

Purpose of the control. A policy and procedure that is designed to prevent or detect and correct a misstatement in a significant FSLI has a more direct (precise) effect on the likelihood of a misstatement than a policy and procedure that is only identified if another control is not operating effectively or a matter requiring follow‑up. We distinguish the purpose of information processing controls and direct entity level controls (Direct ELC), which are controls designed to prevent or detect and correct material misstatements, and an indirect entity level control (Indirect ELC) that supports the entity’s other components of internal control over financial reporting.

-

Alignment between the controls and risks of material misstatement identified. Our evaluation will focus on whether the business processes and related controls are effective in achieving the control objective(s) and reducing the financial reporting risks.

-

Whether the control helps to satisfy the information processing objectives of completeness, accuracy, validity and restricted access. See OAG Audit 5035.4 for further guidance on information processing objectives.

-

Nature of the control, including its level of disaggregation. For example, a high level business performance review (i.e., designed as a Direct ELC) may provide some assurance across a range of assertions, but detailed transaction controls may provide more assurance over specific assertions.

-

Consistency and timeliness of the control. This will affect whether the control will detect or prevent the risk identified on a timely basis. In some cases, a detective control may be adequate, but in other cases, the entity would put in place adequate preventive controls. Controls performed routinely and consistently are generally more precise than one performed sporadically.

-

Knowledge and experience of the people involved in performing the controls.

-

Segregation of duties relevant to the process being controlled. See OAG Audit 5035.3 for further guidance on segregation of duties.

-

Follow up actions taken by the entity. For a control to be effective there needs to be adequate follow up of issues and exceptions, in a timely manner. A threshold for investigating differences relative to materiality is an indication of a control’s precision. The closer a threshold is to materiality, the greater the risk that the control may not detect or prevent a material misstatement.

-

Reliability of the information used in the performance of the control. Understand how management gets assurance that financial information is reliable.

-

Predictability of expectations. The precision of a control depends on the ability to develop sufficiently precise expectations to highlight potentially material misstatements.

-

Period covered by the control. For audit purposes, we need to obtain evidence that a control has been implemented for the reporting period.

We may determine that a control is not designed appropriately. For example, an entity may have a control that all changes to the approved vendor master listing are reviewed and approved. However, our design procedures identify that the individual with the review and approval responsibility also has the ability to request changes to the vendor listing. We assess the impact of this design failure to our audit strategy and assess whether a control deficiency impacting the financial statements exists and if so its severity (see OAG Audit 5037).

Determining whether controls have been implemented

After evaluating the design of the controls that are within the control activities component we obtain evidence to determine whether those controls have been implemented.

Determining whether controls have been "implemented" is different from testing the operating effectiveness. Implementation is evidenced at a point in time, while evaluating operating effectiveness involves testing the operation of a control over the audit period. In practice that means we observe or inspect a minimum of one occurrence based on professional judgment of the control to determine whether the control has been implemented during the period.

When evaluating whether controls have been implemented we apply our professional judgment and consider the "ExCUSME" framework, which includes the following elements:

-

Existence – the control is present within the organization

-

Communication – the existence of a control needs to be conveyed to relevant people

-

Understanding – to be effective the control needs to be understood by the relevant people, including their roles and responsibilities

-

Support – to facilitate an effective implementation the control needs to be supported

-

Monitoring – to verify the quality of the control it needs to be monitored

-

Enforcement – in order for the control to be effective it needs to be enforced by management It is not necessary to specifically document our consideration of individual "ExCUSME" elements.

Timing Considerations for Obtaining/Updating Our Understanding of Controls

We normally obtain and/or update our previous understanding of the entity’s business processes, including the flows of transactions and controls within the control activities component during the planning phase of the audit before setting our audit strategy. However, in certain recurring audits it is inefficient and/or impracticable to perform these risk assessment procedures beyond inquiry during the planning phase. For example, in cases where our audit fieldwork is performed in a single period following the entity’s year-end. In such cases, we may perform these procedures during year‑end field work to validate that the design of controls has not changed or only changed where expected due to changes in the entity and its environment and remain implemented during the current period. This may be accomplished concurrent with our testing of the operating effectiveness of internal controls and/or concurrent with the performance of substantive procedures. We consider the following factors, where applicable, when determining whether to perform these risk assessment procedures concurrent with control or substantive testing procedures:

-

Results of previous audits have indicated few deficiencies and no significant deficiencies in controls, and management has historically taken appropriate action to address identified deficiencies.

-

Results of inquiries of management performed during the current period have indicated that

a) there are no changes in the entity and its environment that would impact the design or operation of controls (including ITGCs) during the current period and

b) there have been no changes made to controls since our previous audit and there are no current plans to implement any such changes prior to the period-end.

-

Results of obtaining an understanding and evaluation of the control environment, the entity’s risk

assessment process, and the entity’s process to monitor the system of internal controls and information system and communication have not identified any deficiencies during the current period. - We will be able to satisfactorily address any changes we need to make to our audit strategy necessitated by matters that arise when we later perform procedures (i.e., after the point of Planning Sign‑off in the audit working paper software) to determine the implementation of controls.

The decision to wait until we are performing testing of control effectiveness or substantive testing to execute procedures necessary to determine that controls have been implemented is a significant audit strategy decision. Accordingly, this determination needs to be made for each relevant business process and based on the facts and circumstances of each engagement with the support of the engagement leader. In making this determination the engagement leader would need to have a high degree of confidence that performing procedures at this later stage of the audit will not result in the identification of new information that may impact the audit strategy, or that adequate time will be available to adjust the audit strategy if necessary.

Assessing the results of understanding controls

We evaluate the results of understanding the components of internal control and the impact of any deficiencies identified in the entity’s control environment, entity’s risk assessment process, the entity’s process to monitor the system of internal control, information system and communication on our audit strategy and plan as early in the audit process as practical. As a result of our evaluation, we may determine that it is not practical to test the operating effectiveness and rely on controls at the group or its components, or we may alter the nature, timing, and extent of our testing of controls and substantive procedures. We document conclusions clearly in our workpapers.

As explained by CAS 330.A20, tests of the operating effectiveness of controls are performed only on those controls that we have determined are suitably designed to prevent, or detect and correct on a timely basis, a material misstatement in an assertion and that it will be efficient to test.

See OAG Audit 6050 for guidance on developing our controls test plan.

Where understanding controls may be sufficient for testing operating effectiveness

In certain circumstances the procedures necessary to evaluate design effectiveness and assess implementation of controls may be consistent with those necessary to test their operating effectiveness. For example, when we have obtained evidence of the effective operation of an entity’s information technology general controls (ITGC’s) and specifically controls over program changes, procedures performed to determine whether an automated control is designed appropriately and has been implemented may also satisfy as a test of operating effectiveness.

Also, the procedures performed to evaluate the design of controls and determining whether the control has been implemented may provide sufficient evidence of operating effectiveness of indirect entity level controls (indirect ELCs) (i.e., application of controls sample sizes table in OAG Audit 6053 is generally not required for indirect ELCs) as these controls operate at a high level within the entity and may not provide precise information to prevent or detect material misstatements. However, they do provide a good framework in assessing whether internal controls are implemented at the entity and thus it is important to understand them.

Methods to understand, evaluate design and determine whether controls have been implemented

We employ various methods to obtain and document our understanding, evaluation of design and determination of implementation of controls within the control activities component. These methods vary by audit and business process. Examples of methods to use to obtain an understanding include:

-

Review of entity-prepared documentation (i.e., policies and procedures, narratives, flowcharts, mapping diagrams, contracts). When we use system flow charts and other documentation prepared by an internal audit or equivalent function, refer to OAG Audit 6033 for guidance.

-

Preparation of business process documentation (inclusive of narratives, mapping diagrams, overview flowcharts) by the engagement team based upon inquiries and other procedures. Inquiries of management could include inquiries of, for example:

- personnel in the finance/accounting department

- business process owners

- control operators/reviewers

- internal audit

- information systems/application owners

Examples of methods to use to evaluate design and determine whether controls have been implemented include:

-

Observe the operation of the control e.g., observing inventory cycle counts, business performance

review meetings, Board of Directors or Audit Committee meetings, application of HR policies -

Inspect evidence that the control operated as designed e.g., obtaining and inspecting a manual shipping log which includes evidence of authorization

-

Obtain documentation prepared by internal audit or equivalent function and perform appropriate procedures to validate the information based on inquiry, observation and/or inspection to obtain sufficient understanding of internal control.

We tailor our approach by performing one or more of the aforementioned methods as applicable based upon the nature, size and complexity of the business processes, transaction flows, and individual control. We choose a method, beyond inquiry, that allows us to satisfy our objectives while providing the optimal balance of effectiveness and efficiency. For example, on a larger engagement where we perform interim fieldwork, we may choose to understand and evaluate controls by observing or inspecting evidence of the controls during planning.

An acceptable method is any which allows us to

(a) obtain an understanding of controls sufficient to properly assess risks of material misstatement due to error or fraud and design the nature, timing and extent of further audit procedures (inclusive of tests of controls and substantive procedures), and

(b) sufficiently document the foregoing in a manner that can be understood by an independent reviewer. We choose the method that allows us to satisfy these objectives in an efficient manner.

OAG Guidance

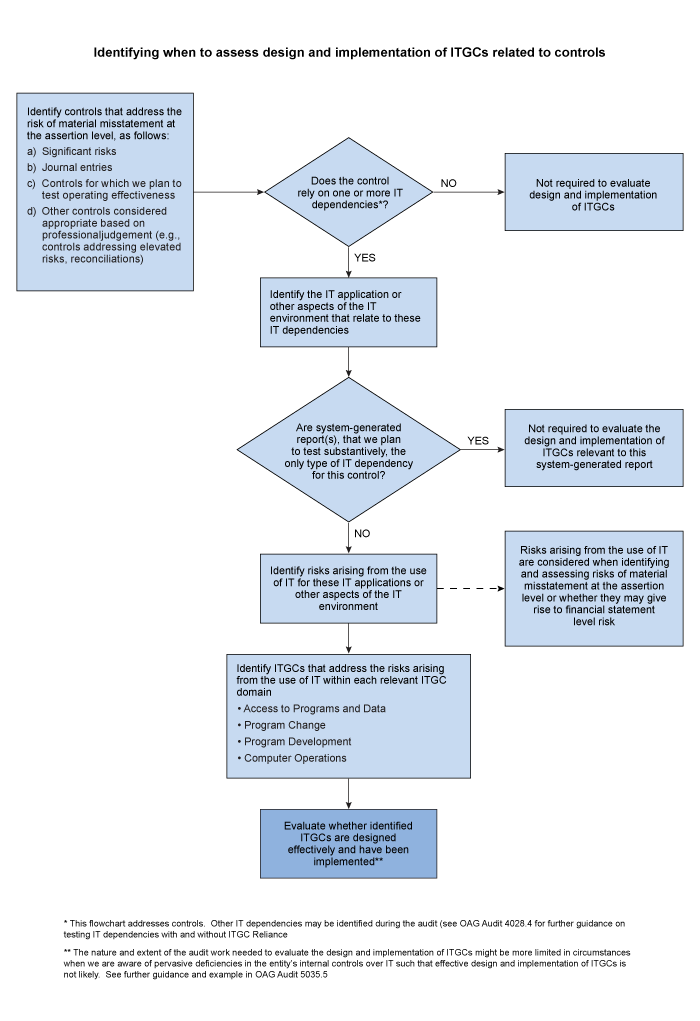

The flowchart in OAG Audit 5035.2 (and copied below) illustrates the process we follow to identify IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment related to identified controls that address risks of material misstatement. We consider which of these applications or other aspects of the IT environment are subject to risks arising from the use of IT, and as explained in OAG Audit 5035.2, we identify ITGCs that address risks arising from the use of IT. For ITGCs that address risks arising from the use of IT, CAS 315.26(d) requires that we evaluate their design and determine whether they have been implemented.

The following flowchart illustrates the process we follow to identify IT applications and other aspects of the IT environment related to controls that are subject to risks arising from the use of IT, the related ITGCs that address the risks and when it is necessary to assess the design and implementation of these ITGCs.

Understanding the design of ITGCs can be done using existing documentation along with a combination of inquiry, observation, and inspection procedures. Although there is no requirement to perform walkthroughs of ITGCs, in some cases a walkthrough may be an effective technique for obtaining evidence about the design and implementation of ITGCs.

We may consider our knowledge and experience from prior audits when evaluating the design and implementation of ITGCs. For example, if in our prior year audit we identified deficiencies in the design or implementation of controls in the IT environment and concluded they were ineffective, we would update our evaluation and assess whether management has remediated the deficiencies. Typically, it would be necessary to obtain relatively limited evidence to confirm that ITGCs with deficiencies remain ineffective.

Where we identify an IT dependency relevant to our audit that is potentially impacted by one or more ITGC deficiencies, we do not necessarily conclude that the IT dependency cannot be relied upon in our audit. If we are able to obtain audit evidence demonstrating that ITGC deficiency has not been exploited, we may still be able to rely upon the IT dependent audit evidence. For example, if there is an ITGC deficiency that could allow direct changes to the underlying data supporting a system generated report, but the reliability of information in the system generated report can be established through substantive procedures for each instance of the report used in our audit work, the existence of deficiencies in ITGCs would not preclude us from relying on the report.

Example:

The following control has been identified in relation to the entity’s significant FSLI, accounts payable. We followed the steps in the above flowchart to identify IT dependencies, related aspects of IT environment subject to risks arising from the use of IT, and the related ITGCs that address these risks:

| Information Processing Control | IT Dependency | IT environment | Risk arising from use of IT | ITGCs that address the risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconciliation between supplier statements and corresponding accounts payable subledger balances are reviewed and approved by a supervisor each month. Differences above $5,000 are investigated and resolved before the completion of the monthly financial close. | Standard system generated detailed listing of supplier invoices, including date issued, amount and total value of unpaid invoices by supplier extracted from the accounts payable database / data | Application ABC used to generate the report. |

As the standard system generated listing relies on standing data from the AP database, there is a risk of improper direct changes to underlying transaction records or master data impacting subledger transactions and balances. Unauthorized or untested, or failure to make necessary changes, prevent the listing from providing transaction records completely and accurately (this risk would be present however, it is not the focus of this example) |

We identify the following controls: - All access requests for either new or existing database/data file users are reviewed for compliance with the company’s working practices/ policies to ensure access rights are commensurate with job responsibilities, approved by an appropriate individual and entered accurately into the system. - Management reviews database/ data file access rights periodically to ensure individual access rights are commensurate with job responsibilities. Exceptions noted are investigated and resolved on a timely basis. |

When evaluating the design and implementation of the relevant ITGCs to address the IT risk in relation to changes to the accounts payable database/data, we identify that although the entity has a process to grant access rights commensurate with job responsibilities, and to ensure these access rights are approved and entered accurately in the system and monitored periodically, the design of certain roles allows personnel to make changes in the accounts payable database which is incompatible with their responsibilities to process financial transactions, creating a risk that data change controls could be bypassed. We also identify there are no logging and monitoring or review controls implemented to detect direct changes to the accounts payable database. We determined the design of the controls to address the risk of improper changes to the accounts payable database is not effective because certain roles which include processing of financial transactions and also allow personnel to bypass data change controls. Therefore, we conclude that this deficiency increases the control risk, and would impact our expected controls reliance for this reconciliation control because the effectiveness of this control depends on the reliability of the information in this AP balance report. Before concluding that we cannot rely on the AP reconciliation control, we might consider whether there are other (compensating) controls identified later in the accounts payable reconciliation process that sufficiently address the risk of inaccurate or incomplete customer AP balances being reflected in the system-generated report.