Performance Audit Manual

COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

6010 Evidence-Gathering Methods

May-2024

Overview

In order to plan the audit strategy, the engagement team thinks through how it will gather sufficient appropriate evidence to enable it to conclude against the audit objectives. This work is documented in the audit logic matrix (ALM) and further expanded in audit programs.

Financial Administration Act Requirements for Special Examinations

FAA 138(5): An examiner shall, to the extent he considers practicable, rely on any internal audit of the corporation being examined conducted pursuant to subsection 131(3).

OAG Policy

Engagement teams shall obtain sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to provide a reasonable basis to support the conclusion(s) expressed in the assurance engagement report. [Nov-2011]

Engagement teams shall design detailed audit programs, setting out the procedures that are appropriate to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence through the selected use of

- inspection

- observation

- external confirmation

- recalculation

- reperformance

- analytical procedures

- inquiry [Nov-2011]

When using data as input to perform audit procedures or to support audit findings and conclusions, the engagement teams shall evaluate whether the data is reliable for its intended purpose, including obtaining audit evidence about its completeness and accuracy. [May-2024]

Definitions

Per the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance, the following terms have the meanings attributed below:

Audit evidence—Information used by the practitioner in arriving at the practitioner’s conclusion. Evidence includes both information contained in relevant information systems, and other information.

Appropriateness (of audit evidence)—The measure of the quality of audit evidence; that is, its relevance and its reliability in providing support for the practitioner’s conclusion.

Sufficiency (of audit evidence)—The measure of the quantity of audit evidence. The quantity of the evidence needed is affected by the risks of the underlying subject matter containing a significant deviation (the higher the risks, the more evidence is likely to be required) and also by the quality of such evidence (the higher the quality, the less may be required).

Criteria—The benchmarks used to measure or evaluate the underlying subject matter. The “applicable criteria” are the criteria used for the particular engagement. (Ref: Para. A12, Appendix 2).

Audit procedure—Tasks performed by an auditor designed either to gather audit evidence as a basis for assessing and/or responding to risk or other audit work that is necessary to comply with requirements. The performance of audit procedures collectively enables the auditor to comply with standards, draw conclusions, and support the audit opinion.

Underlying subject matter—The phenomenon that is measured or evaluated by applying criteria.

OAG Guidance

What CSAE 3001 means for evidence-gathering methods

CSAE 3001 requires sufficient appropriate evidence to be obtained in order to support the conclusion of the assurance report. It notes that “sufficiency is the measure of the quantity of evidence” and “appropriateness is the measure of the quality of evidence (relevance and reliability).”

The decision on whether enough evidence has been obtained will be influenced by the risk of the underlying subject matter containing a significant deviation from the applicable criteria used to evaluate it (the higher the risks, the more evidence is likely to be required) and also by the quality of such evidence (the higher the quality, the less amount of evidence may be required). Evidence for an “audit level of assurance” is obtained by different means and from different sources as described below.

Audit evidence

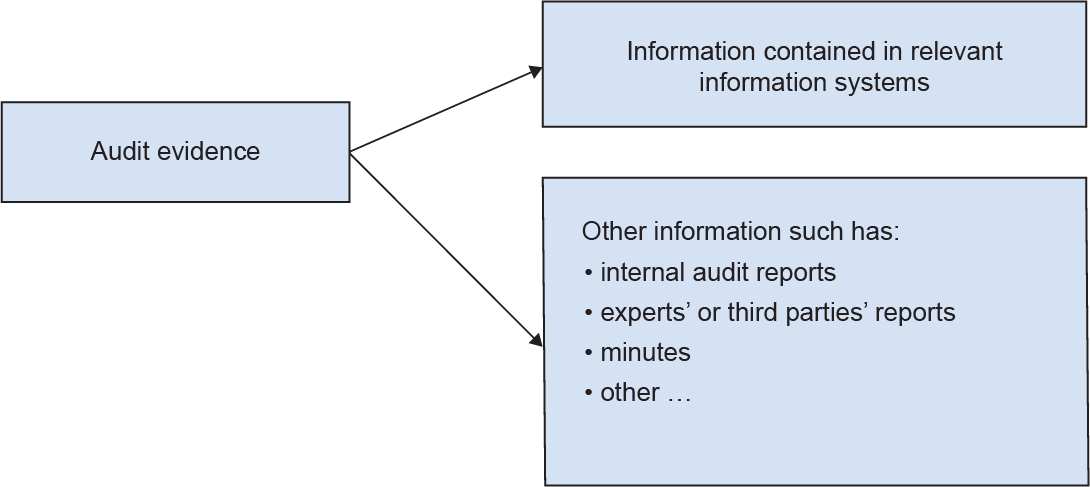

Audit evidence is information used by the practitioner in arriving at a conclusion. Evidence includes both information contained in relevant information systems, if any, and other information (Exhibit 1). Evidence provides grounds for concluding that a particular finding is true by providing persuasive support for a fact or a point in question. Evidence must support the contents of an assurance report, including any descriptive material, all observations leading to recommendations, and the audit conclusions.

Exhibit 1—Sources of audit evidence

It is important that the engagement team obtain evidence from a variety of sources, as different perspectives and conclusions may be presented from multiple sources.

There are 4 types of audit evidence that can be used by engagement teams (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—Types of audit evidence

| Type of evidence | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical evidence | Evidence that is obtained by the auditor’s direct inspection or observation. This is done by seeing, listening, and observing directly by the auditor, including for example work shadowing, observing silently, taking videos or photos, or mystery shopping. |

| Testimonial evidence | Evidence that is obtained from others through oral or written statements in response to an auditor’s inquiries. Techniques that could be used to gather testimonial evidence include interviews, focus groups, surveys, expert opinions, and external confirmation. |

| Documentary evidence | Evidence that is obtained from information and data found in documents or databases. Techniques that could be used to gather documentary evidence include entity’s documents, file reviews, databases and spreadsheets, internal audits and evaluations, reports from consultants, studies from other jurisdictions, recalculation, and reperformance. |

| Analytical evidence | Evidence that is obtained by examination and analysis of plausible relations among and between sets of data. These analyses may include statistical analysis, data analytics, regressions, benchmarking and comparisons, simulation and modelling of quantitative data, and text mining or content analysis of qualitative data. |

Obtaining audit evidence

Audit evidence can be obtained directly or indirectly (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3—Direct and indirect evidence

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Directly obtained evidence | Evidence that is obtained through the team’s direct examination. Some of the procedures used include but are not limited to observation, computation, and inspection; for example, observation that a control has been applied. |

| Indirectly obtained evidence | Evidence that is obtained through others, such as reports from internal audits, experts, or third parties. |

Designing evidence-gathering procedures

Engagement teams can use different audit procedures to gather audit evidence. The following table provides a brief description of each evidence-gathering procedure (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4—Evidence-gathering procedures

| Procedure | Description |

|---|---|

| Inspection | Inspection involves examining records or documents, whether internal or external, in paper form, electronic form, or other media, or physically examining an asset. |

| Observation | Observation consists of looking at a process or procedure being performed by others. |

| External confirmation | An external confirmation represents audit evidence obtained by the auditor as a direct written response to the auditor from a third party (the confirming party) in paper form or by electronic or other medium. |

| Recalculation | Recalculation consists of checking the mathematical accuracy of documents or records. |

| Reperformance | Reperformance involves the auditor’s independent execution of procedures or controls that were originally performed as part of the entity’s internal control. |

| Analytical procedures | Analytical procedures consist of examining and analyzing plausible relations among and between sets of information or data. |

| Inquiry | Inquiry consists of seeking information of knowledgeable persons, both financial and non-financial, within the entity or outside the entity. |

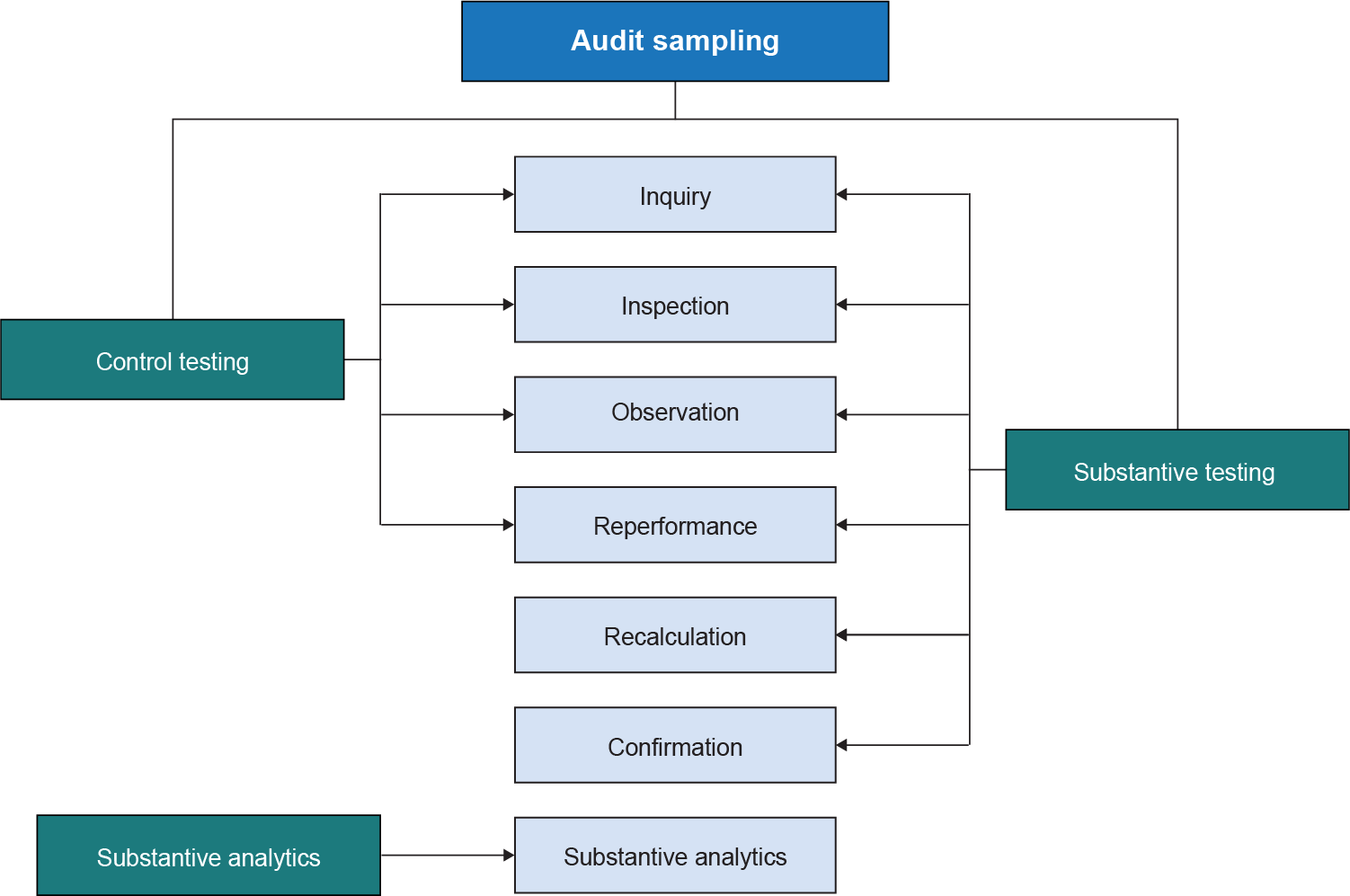

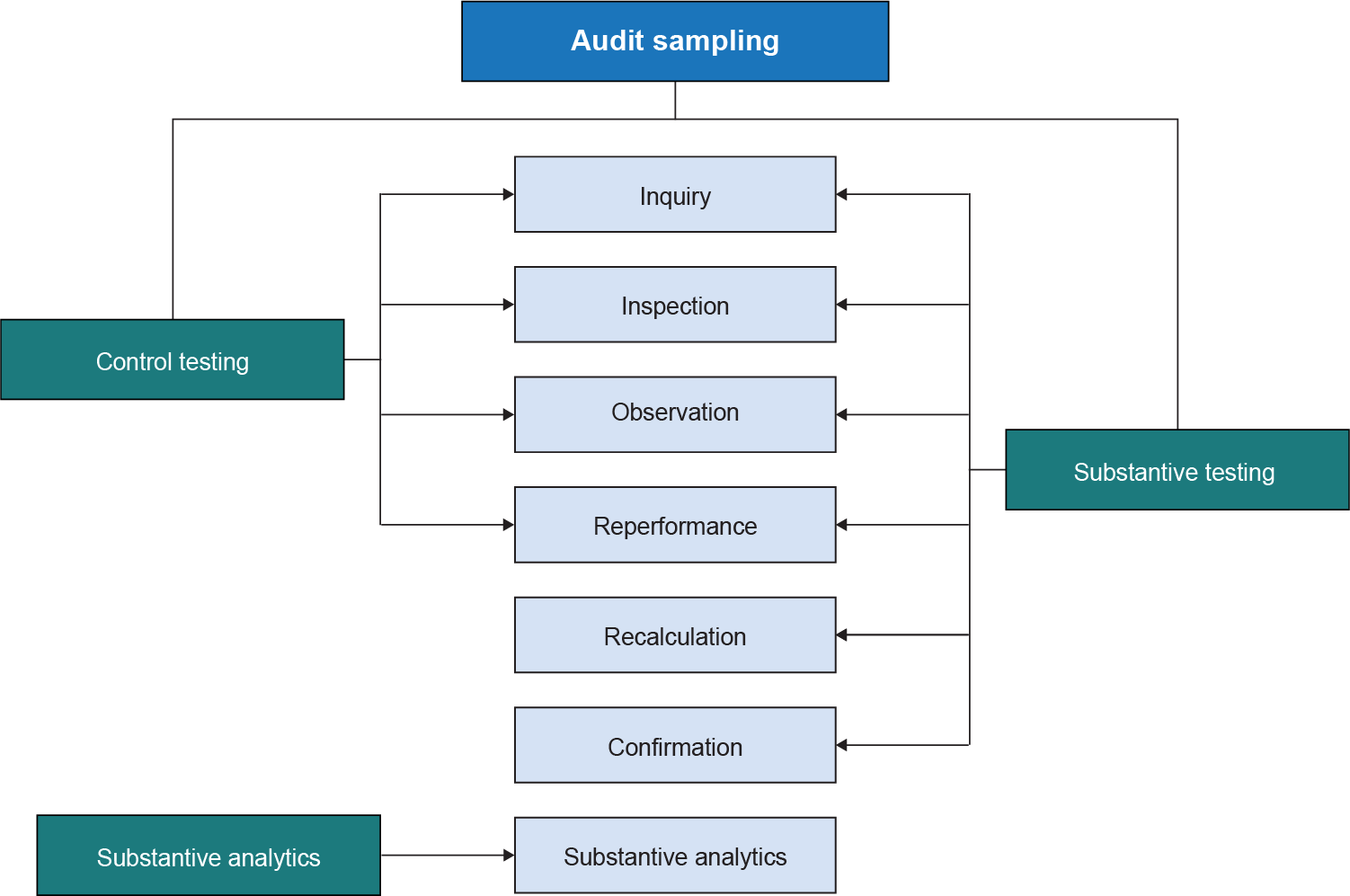

These evidence-gathering procedures can be used to perform different type of tests as presented in the table below (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5—Types of tests

| Test type | Description |

|---|---|

| Control testing | An audit procedure designed to evaluate the operating effectiveness of controls in preventing, or detecting and correcting, deviations against the criteria. |

| Substantive testing | Tests involving the examination of support for individual items that make up the population under review. |

| Substantive analytics | Evaluations of information through analysis of plausible relationships among data. Analytical procedures also encompass such investigation as is necessary of identified fluctuations or relationships that are inconsistent with other relevant information or that significantly differ from expectations. Analytical procedures may be used at all stages of the audit. |

The flow chart below shows the relationships between the evidence-gathering procedures and the different type of tests (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6—Relationships between procedures and types of tests

The evidence-gathering methods shall be designed and performed in order to respond to the assessed risks of significant deviation from the applicable criteria used to evaluate the subject matter. The ALM (OAG Audit 4044 Developing the Audit Strategy: Audit Logic Matrix) sets out the methods that the team expects to use for evidence gathering and analysis. Engagement teams should describe in the ALM how they will gather audit evidence to assess whether the assessed risk of significant deviation from the applicable criteria has been addressed and the audit criteria have been met, thus allowing them to draw conclusions against the audit objectives. The ALM then guides the development of audit programs, which describe in more detail how the engagement team intends to gather evidence (OAG Audit 4070 Audit Programs). Audit procedures can be incorporated into the ALM or in separate audit programs.

More information on evidence-gathering procedures can be found in the Evidence and Evidence-Gathering Techniques.

Type of audit evidence

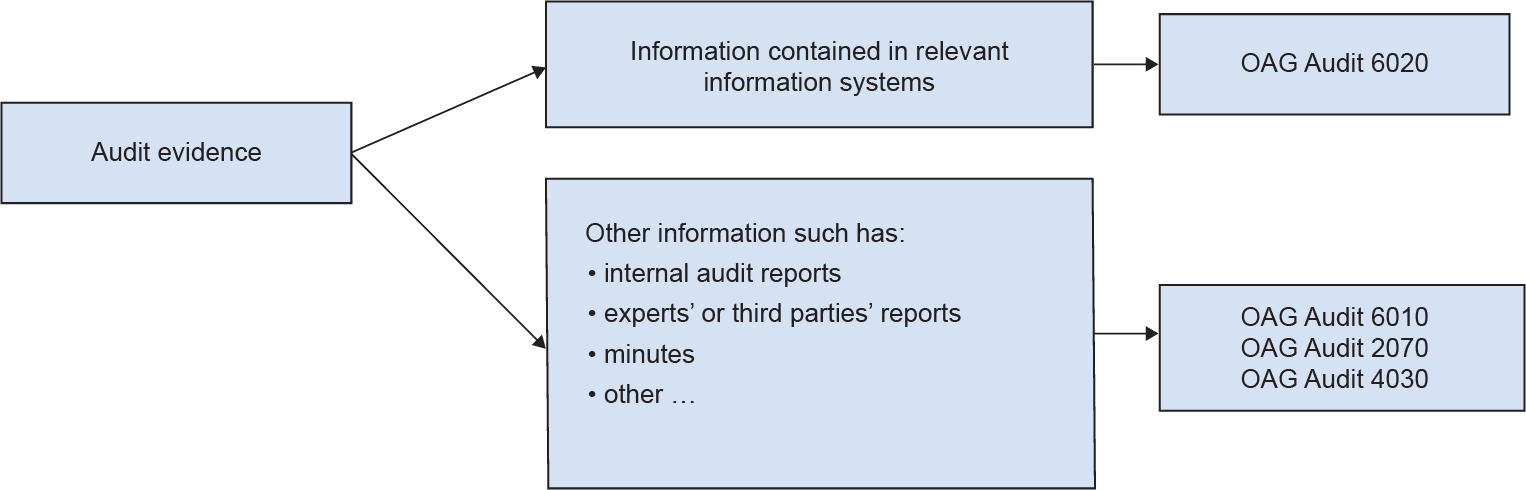

As mentioned previously, evidence can be obtained in the form of information contained in relevant information systems or other information (Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7—Sources of audit evidence

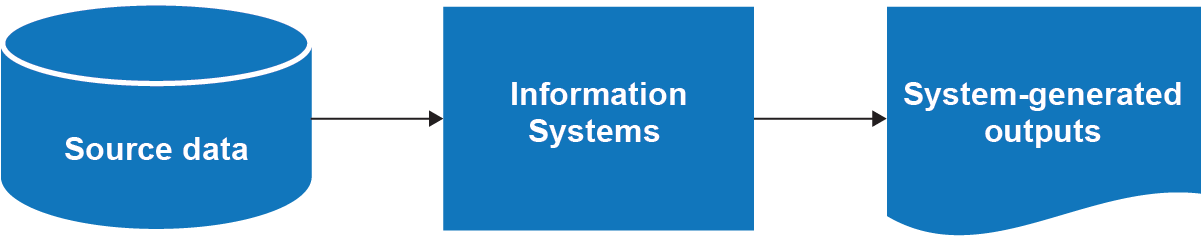

Information contained in relevant information systems

Information contained in relevant information systems may vary widely in form from source data, a digital representation of facts, transactions, or events, to information in system-generated outputs (Exhibit 8). OAG Audit 6020 Assessing the Reliability of Data contains relevant information on this topic and sets out the procedures that engagement teams may use to assess the reliability of source data and system-generated outputs.

Exhibit 8—Types of information

Other information

There is a wide range of other information that could be used as evidence by engagement teams. Below are some examples of the most common “other information” used as evidence in direct engagements.

-

Information obtained from experts or internal audit

The engagement team may rely on the work performed by experts and the internal audit function and assess whether the work performed by them can be used as audit evidence.

CSAE 3001 requires considering many matters before relying on the work performed by a practitioner’s expert, entity’s expert, or the internal audit function. More information on these matters can be found in OAG Audit 4030 Reliance on Internal Audit and OAG Audit 2070 Use of Experts.

- Information not contained in relevant information systems provided by entity officials

This is information such as records of minutes, hard copy files, reports, testimony, or other. The engagement teams may find it necessary to test management’s procedures or directly test the information to obtain assurance about the accuracy and completeness of the information received.

- Information obtained by an external source

This is information such as published statistics and information from a supplier or contractor.

Determining the extent of the reliability assessment

Engagement teams should consider the elements below when determining the extent of the assessment:

- the purpose for which the information is used

- the significance of the information as evidence

- the risks that the information is not reliable

There is no specific formula or recipe to precisely determine the extent of work to assess the reliability of information. Engagement teams need to consider the elements listed above and conclude based on their professional judgment.

The purpose for which the information is used

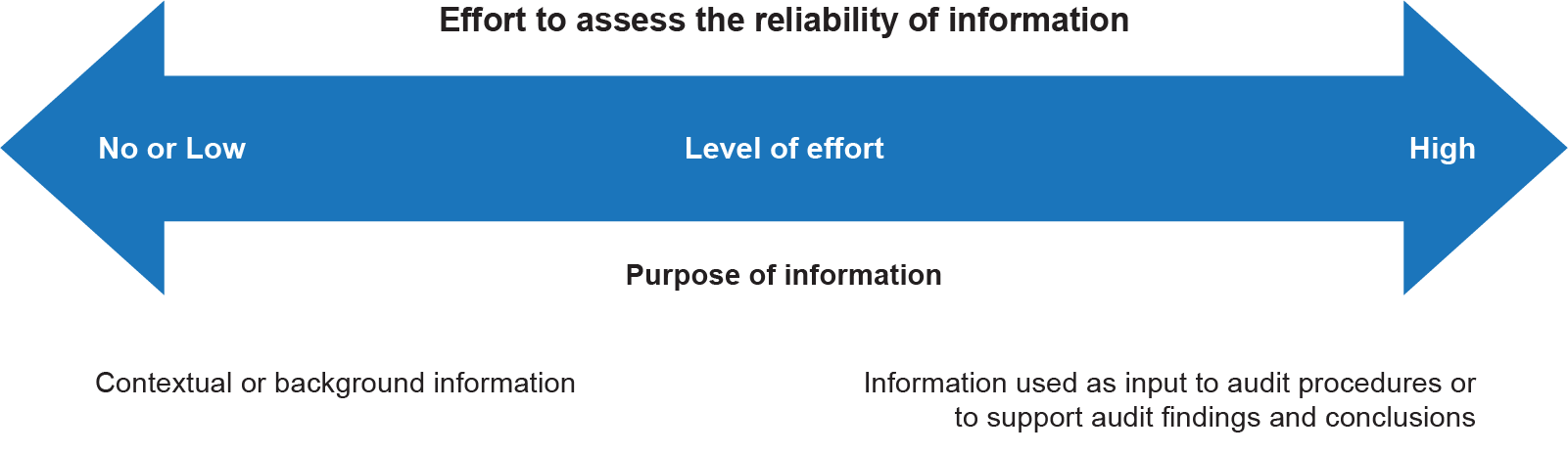

The purpose for which the information is to be used will affect the level of effort and the nature of audit evidence required (Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 9—Purpose for using the information in a direct engagement

Engagement teams will need to devote no or less effort when assessing the credibility of information to be used as contextual information or background information as opposed to information used to support audit procedures, audit findings, and conclusions as described in the exhibit above.

Contextual or background information

Background information generally sets the tone for reporting the engagement results or provides information that puts the results in proper context. Information used as contextual or background information in the assurance report is typically not evidence supporting the audit conclusion. While it is not supporting the audit conclusion, it is still important that such information be credible. Credibility of the information refers to whether the source has the competence to generate the information and whether the source can be trusted.

Factors

There are multiple factors that engagement teams may consider when assessing the credibility of contextual or background information, depending on whether the information is obtained from the entity or not.

Factors the practitioner may consider in assessing the credibility of information obtained from the audited entity may include

- engagement teams’ knowledge of the operations and business that underlie the functioning of the database or information source

- level of knowledge, competency, and skills of those in charge of such information

- controls over the credibility of the information

- extent of work performed by the entity to ensure that the information is credible

- existence of any quality test performed that satisfies engagement teams’ needs

Factors the practitioner may consider in assessing the credibility of information from an external source may include

- the nature and authority of the external source; for example, a central bank or government statistics office with a legislative mandate to provide information to the public

- whether the entity has the ability to influence the information obtained from the external source

- evidence of general market acceptance by users of the relevance and/or reliability of information

- the nature and extent of disclaimers or other restrictive language relating to the information obtained

Procedures

When contextual or background information is obtained from the best available external sources, generally recognized as known to be reliable, there is no need to assess its completeness and accuracy. For example, such information may include price indices or inflation rates published by the Bank of Canada.

Simple attribution to the source (to an entity or a third party), although always useful and advisable, could be insufficient in some cases. For example, when the contextual or background information is obtained from the audited entity or is from an unknown or non reliable source, engagement teams need to devote a minimum of effort to assess the credibility of such information. This also applies when the audited entity obtained the information from an external source and modified it.

The table below outlines some procedures that engagement teams may use to assess the credibility of the contextual or background information (Exhibit 10).

Exhibit 10—Procedures for assessing the credibility of contextual or background information

| Procedure | Description |

|---|---|

| Cross-check and compare information | For consistency, cross-check and compare information and findings gathered with the information acquired from other or outside sources. |

| Ascertain the implicit controls in place for publication of research papers and academic studies | When using third-party research papers or academic studies, ascertain the implicit controls in place for publication of those documents (for example, the disclosure policy for a journal). The reputation of the developer of the information and the extent to which its source has been proven by wide use are important factors to note. When using reports from other departments and agencies, check to see if the OAG has in the past conducted an audit of aspects related to that report, such as report methodology or supporting database controls (for example, Statistics Canada). |

| Examine consistency | When using several sources of information (databases, studies, papers, and so on), engagement teams could examine the general consistency of their findings and conclusions. Different information sources providing the same observations can be compelling. It is wise once again to examine these general conclusions with the findings from audit field work. |

Information used as input to audit procedures, findings, and conclusions

Per Exhibit 9, more persuasive audit evidence is needed when information is used as input to audit procedures or to support audit findings and conclusions. Therefore, engagement teams need to devote considerably more effort when assessing the reliability of information to be used as input to audit procedures or to support audit findings and conclusions.

Factors

The engagement team will conduct its own review and analysis of the reliability of information. The following factors, presented in the table below (Exhibit 11), are some considerations to help engagement teams decide whether evidence collected during the engagement is reliable or not.

Exhibit 11—Considerations in assessing the reliability of information

| Factor | Generally more reliable |

Generally less reliable |

|---|---|---|

| Information creator | Independent third party | Entity |

| Internal controls | Effective related internal controls | Ineffective or inexistent related internal controls |

| Directly versus indirectly obtained evidence | Directly obtained evidence, like the observation of the application of a control or the inspection of documents | Indirectly obtained evidence, like inquiring about the application of a control or gathered by others such as internal audit or experts |

| Documentary evidence versus testimonial evidence | Documentary evidence like contracts or detailed meeting minutes | Testimonial evidence obtained from interviews |

| Original documents versus copies | Original documents | Photocopies, facsimiles, scans |

Procedures

All the evidence-gathering procedures and types of tests presented in the flow chart below (Exhibit 12) may be used by engagement teams to assess the reliability of the information.

Exhibit 12—Relationships between procedures and types of tests

Engagement teams can rarely examine an entire population of items, which necessitates their review of just a selection. For more information on the selection of items to review, please refer to OAG Audit 6040 Selection of Items for Review.

When assessing information contained in relevant information systems (such as data), it is essential to consider the reliability of the systems and processes used to produce the information we want to rely on. OAG Audit 6020 Assessing the Reliability of Data contains relevant information on this topic and sets out the procedures that engagement teams may use to assess the reliability of source data and system-generated outputs.

Evaluation of the sufficiency and appropriateness of the evidence gathered

Direct engagements at the OAG are considered “reasonable assurance engagements,” also referred to as “audit engagements,” where the practitioner needs to reduce the engagement risk (risk of expressing an inappropriate conclusion) to an acceptably low level.

The decision on whether sufficient appropriate evidence has been obtained will be influenced by the risks of the subject matter containing a significant deviation from the applicable criteria. The higher the risks of significant deviation from the applicable criteria, the higher the quality and quantity of evidence is required. The decision will also be affected by the quality of evidence obtained. The higher the quality of evidence is obtained, the lower the quantity may be.

For more information on the sufficiency and appropriateness of audit evidence, refer to OAG Audit 1051 Sufficient appropriate audit evidence and OAG Audit 7021 Evaluate the Sufficiency and Appropriateness of Audit Evidence.