COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

103 Root Cause Analysis

Dec-2023

Overview

This section outlines considerations for planning and performing root cause analysis in the conduct of performance audits.

In order to incorporate root cause analysis, audit teams need to consider

- what root cause analysis is

- if there are barriers to its application

- its use in planning the engagement

- its use in performing the engagement

- methods

- reporting

OAG Guidance

What is root cause analysis?

Root cause analysis is the identification of why an issue has occurred, as opposed to identifying only the issue itself. An issue is a gap in performance, an unexpected result, a problem, an error, an instance of non-compliance, a missed opportunity. By identifying the reason(s) that caused an issue, auditors are able to help the audited entity improve its performance (effectiveness and efficiency of operations).

It is important to note that this activity is an analysis, in which the auditors ask “Why did this happen?” and “How did this happen?” This type of thinking is present throughout all phases of an audit engagement, informing the research conducted, the information gathering activities, the audit planning and programs, the evidence collection plan, the interview questions, and so on.

Root cause analysis is not required by auditing standards. However, considering root cause analysis in our engagements could add value to the work we perform. The identification of the underlying causes of our findings can help to formulate more meaningful recommendations that the audited entity can use to improve performance.

The root cause analysis should be planned and started early in the process, not left to the end of the examination phase when recommendations are being drafted. The planning gives the opportunity for the audit team to consider whether root cause analysis can and should be incorporated into the audit.

Should root cause analysis be incorporated into the audit?

In the planning phase, the auditor is acquiring knowledge of the business and assesses significance and risks. Based on the preliminary information collected and analyzed, the auditor becomes aware of existing issues from various sources, such as internal audit, external inspections, financial audits, previous performance audits, and so on. In considering how and when the root cause analysis might be applicable, the auditor considers

- repetitive topics or issues, either raised by more than one source or carried over

- significant risks that have not been mitigated in due time

- issues raised about ongoing problems that require attention or risks that are not being adequately managed

- overall trend of findings that indicates that either (i) the risk profile of the entity has increased or (ii) the internal control system strength is decreasing

- whether a pattern is developing over a range of completed audits, reviews, or inspections that warrants a closer look

Can root cause analysis be incorporated into the audit?

The resources spent on root cause analysis should be proportional to the impact of the issue or potential future issues and risks. In certain circumstances, root cause analysis may be as simple as using a questioning technique, such as the “Five Whys” described below. More complex issues, however, may require a greater investment of resources and more rigorous analysis. Prior to commencing root cause analysis for more complex issues, the auditor should consider potential internal and external barriers to applying root cause analysis. Some barriers might be as follows:

- Root cause analysis may require an extended amount of time to analyze the process, personnel, technology, and data necessary to identify and support the assessment of a root cause.

- Data and information required to perform a proper root cause analysis might not be available.

- Auditors may not have all the skill sets necessary to conduct the specific root cause analysis under consideration. The engagement leader should validate that the experience and expertise of their staff are sufficient to perform the work and consider bringing additional assistance, as needed (for example, practice leadership, experienced auditors, and external consultants).

- Management may be reluctant to support the auditor’s role in root cause analysis. This might be because of the time and resource commitment required from their staff or to focus on the short-term.

- Root cause analysis may lead to identifying root causes that the OAG cannot report on, such as decisions made at a political level.

Performing root cause analysis on audit findings

It is important to identify the need for root cause analysis, as not all issues are worth performing one.

In the planning phase the audit team may establish not only what is happening, but also what should be happening. Work done to support knowledge of business may inform what ought to be in order to better identify gaps and problem areas.

Root cause analysis does not need to be performed for every finding. The audit team uses professional judgment to direct its focus on the significant or systemic (for example, repetitive) issues.

- Significant issues (whether they are related to a critical failure or a significant impact of a failure) are analyzed as a specific process. The specific process involves understanding what happened and drilling down to find out why it happened in the first place.

- Issues may also be analyzed for correlations in order to identify systemic themes for further analysis to determine their causes. (This is called thematic root cause analysis.) Thematic root cause analysis considers the environmental factors that may have contributed to the issues, as they may represent a higher risk for the organization.

During the examination phase, the auditor progresses in the information gathering and analysis to understand what happened. The auditor may continue to ask “Why did this happen?” (that is, why does the condition exist) and determines whether the root cause has been reached or not. It is important to understand the different levels of causes and determine which level of cause is actionable:

- The immediate or proximate cause is the thing that obviously led to the problem; that is, the action or lack thereof that led directly to the condition.

- The contributing or intermediate cause is the thing that set the stage for the problem to occur; that is, the cause (linear or branched) that led to the immediate cause. This may be an actionable cause.

- The root cause is the factor or factors that caused or could cause numerous issues to arise, not just the individual problem that occurred on this occasion; that is, the underlying cause. This may be an actionable cause.

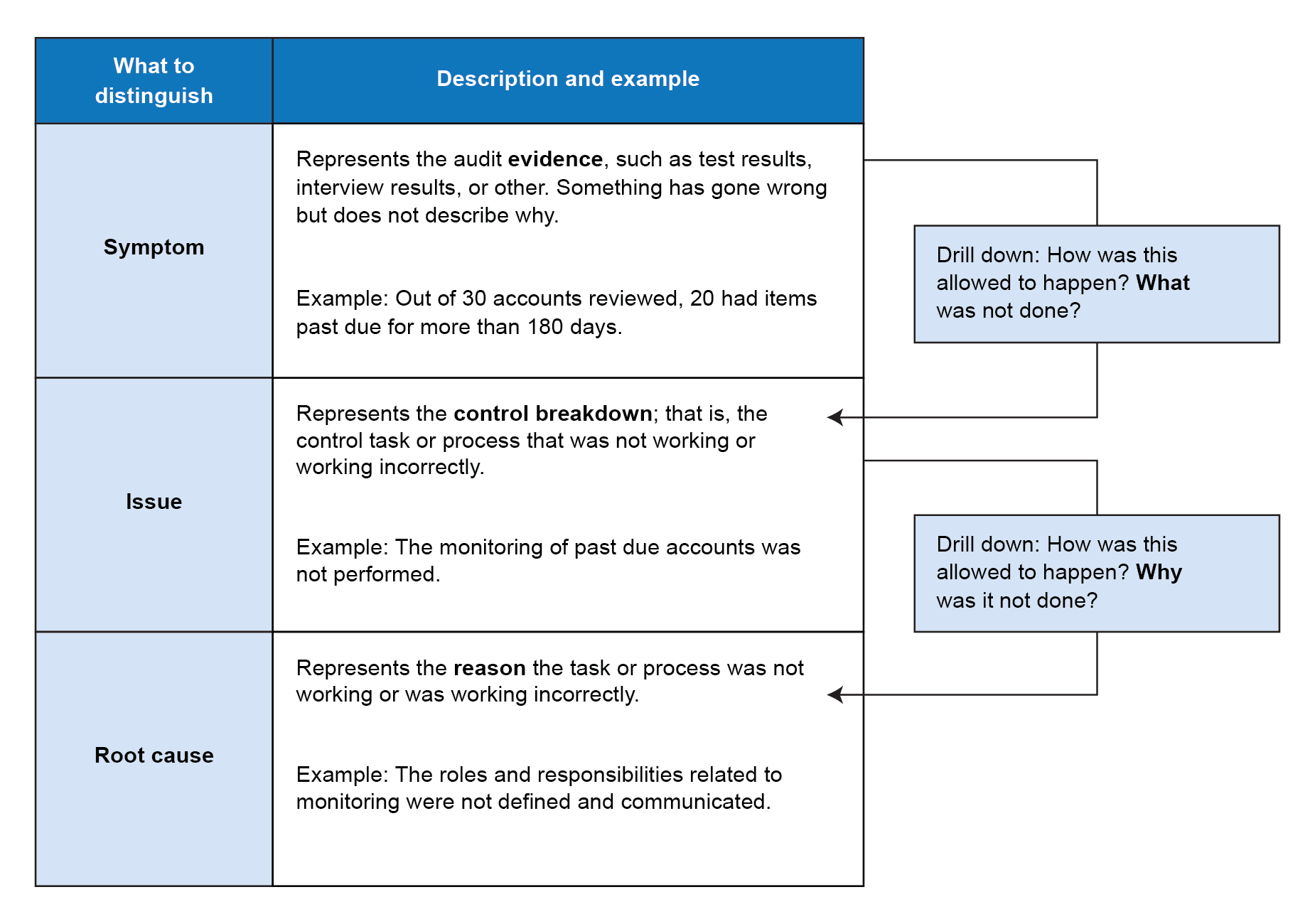

Another way of looking at why this happened is to distinguish what is the symptom, what is the issue, and what is the cause (similar to the levels of causes described above). The differences among the 3 and an example of a simple root cause analysis are provided below:

Attribution: Root cause can be attributed to certain issue types, as in the examples below:

| Type of issue | Root cause considerations |

|---|---|

| Compliance: The entity fails to operate according to the external laws, regulations, and so on. | Root cause might be related to control activities—for example, lack of controls, lack of appropriate control monitoring mechanisms, and so on. This is because compliance with external laws usually requires the development of internal processes and controls that will ensure compliance in the first place, and then adequate monitoring of these controls. |

| Process: The entity fails to meet its objectives. | Root cause might stem from 4 possible sources: infrastructure (IT systems), people (employees), procedures, or external sources. |

| Risk and Control: The entity fails to properly (i) identify risks or (ii) adequately control them. | Root cause might stem from (i) control design or (ii) control operation. Root cause analysis is very beneficial when the auditor finds that the well-designed control activity does not consistently operate effectively. |

| Information Technology General Controls fail to adequately support the entity’s input-process-output. | Root cause might be at a higher level rather than at the technology application level—for example, technological issues can be attributed to lack of competence caused by lack of training, lack of staff, and so on. Consider the design and implementation of Information Technology General Controls. |

As the auditor continues to ask “So what?” To determine the consequence or effect, the auditor identifies the level of the effect:

- direct, one time effect on the process

- cumulative effect on the process

- cumulative effect on the entity

- high-level, systemic effect

These indications should guide the auditor into formulating the finding and designing the recommendation by answering the question “What is to be done?”

Choosing the right technique

There are several techniques available for performing root cause analysis. This manual section describes the Five Whys for illustrative purposes.

The Five Whys is a questioning technique that involves asking the question “Why?” numerous times about the problem or audit finding. The auditor should identify the factors associated with the answer for each iteration. In theory, the root cause will be revealed by the fifth why, hence the name.

The Five Whys technique can help auditors ask probing questions that lead to answers that are in the control of the audited entities. Instead of accepting answers such as a lack of time, money, or human resources, accept answers that could be factual. This technique could generate questions like “Why did the program fail?”

Criticism of the Five Whys include the following:

- Users cannot identify causes beyond their knowledge.

- Re-performance can be challenging. Different users may arrive at different root causes.

- Users may stop questioning when symptoms have been identified instead of root causes.

It may be appropriate to use Five Whys, a different technique, or a combination of approaches. Other questioning techniques are not described in this manual section, such as the fishbone diagram and the Pareto chart.

Validating the root cause

Sufficient and appropriate audit evidence must exist in the audit file to support all findings, including the ones related to root cause. There may be challenges in determining the cause and attributing it to an issue type identified above. There may be several or interrelated causes, each related to a different issue type. Auditors are encouraged to involve the entity in the root cause analysis or at least its validation.

Bringing the issues together

Auditors should focus on causes over which management has control and for which meaningful recommendations for improvements can be made. There are cases when the results of the root cause analysis do not provide for immediate results, but rather they are preventative and might require time and resources to correct. For issues that require long-term fixes with a large impact on resources, time, or cost, the auditor might suggest both an immediate or short-term mitigation in addition to the costlier long-term solution.

When bringing the issues together, the auditor may identify a number of actions or recommendations that are linked in terms of root cause, thus allowing for combined findings. The recommendation should resolve the actionable root causes and their related issues and remediate the symptoms or the condition (that is, the current state).